David Sandner is the author of the scholarly book The Fantastic Sublime: Romanticism and Transcendence in Nineteenth-Century Children's Fantasy Literature and the editor of Fantastic Literature: A Critical Reader. His work has appeared in Realms of Fantasy, Asimov's Science Fiction, Pulphouse, Weird Tales, and the anthology Baseball Fantastic edited by W. P. Kinsella. Sandner is a professor at California State University Fullerton, where he teaches nineteenth-century British Literature, children's literature, gothic, science fiction, and fantastic literature.

Jacob Weisman (editor) is the World Fantasy Award-winning co-editor of The New Voices of Fantasy (with Peter S. Beagle). He is the publisher at Tachyon Publications, an acclaimed San Francisco-based speculative fiction press, which he founded in 1995. Weisman is the series editor of Tachyon's critically acclaimed, award-winning novella line, including the Hugo Award-winner, The Emperor's Soul by Brandon Sanderson, and the Nebula and Shirley Jackson award-winner, We Are All Completely Fine by Daryl Gregory. He has also edited the anthologies Invaders: 22 Tales from the Outer Limits of Literature, and The Sword & Sorcery Anthology (with David G. Hartwell).

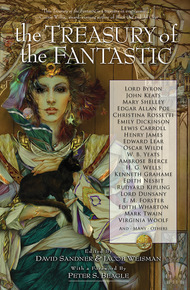

Forty-four classic tales from British and American fantasy icons of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The fantastic, the supernatural, the poetic, and the macabre entwine in this incomparable culmination of storytelling. Major literary figures from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—including Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Keats, Mary Shelley, Emily Dickinson, H. G. Wells, Rudyard Kipling, Mark Twain, Virginia Woolf, Robert Louis Stevenson, Edith Wharton, Edgar Allan Poe, Oscar Wilde, and many more—these masters of literature created unforgettable tales where goblins and imps comingle with humans from all walks of life.

This deftly curated assemblage of notable classics and unexpected gems from the pre-Tolkien era will captivate and enchant readers. Forerunners of today's speculative fiction, these are the authors that changed the fantasy genre forever.

A must-have collection of classic stories by authors so famous it seems almost ridiculous to have them all in one volume. H.G. Wells, anyone? Oscar Wilde? Mary Shelley? Emily Dickinson! Sometimes we forget that the classics are classics for good reason. These are the people who inspired and informed the fantasy writers who followed—and still shape those of us writing now. Not to be missed. – Sandra Kasturi

"A marvelous mix of classics and rarely seen works, bibliophile's finds and old favorites . . . a treasury in every sense and a treasure!"

– Connie Willis, author of Doomsday Book and To Say Nothing of the DogThis is an important collection for all lovers of fantasy and literature."

– Library Journal"The fantasy tradition in English and American literature is rich and varied and strange. This is the book to read to find out what you never knew you needed to know."

– David G. Hartwell, editor of the Year’s Best Fantasy series"The Treasury of the Fantastic is truly that, a comprehensive collection of fantastical literature from throughout the many years covering the romanticism era to the early twentieth century . . . an exquisitely curated collection."

– The Arched DoorwayFrom "Forword" by Peter S. Beagle

When I was a boy—I can't give you the exact geological period, but I do recall my mother complaining about the pterodactyls messing right in front of the cave—fantasy fiction was not considered a separate and unequal species, distinct from real writing. Stephen Vincent Benét's celebrated tales, "The Devil and Daniel Webster" and "Johnny Pye and the Fool-Killer," were published in The Saturday Evening Post, not in Galaxy or Astounding; nor were Ambrose Bierce's "An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge," Rudyard Kipling's "They," Virginia Woolf's "A Haunted House," Edith Wharton's "The Eyes" or Mark Twain's "The Mysterious Stranger" treated as anything but proper literature. Henry James wrote enough ghost stories to fill a book; E. M. Forster's "The Machine Stops" literally grows more prophetic by the day; and James Branch Cabell was regarded seriously enough to be tried for obscenity. J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings trilogy was reviewed on the front page of the Times Book Review—and by W. H. Auden—when it was first published in the United States in 1954. The many novels of Robert Nathan, my own artistic role model, were regularly reviewed in the New York Times, as were my first two books. Science fiction still had a pulp magazine reputation to live down, and the late, lovely Anthony Boucher was the Times' single mystery critic, granted; but fantasy was generally considered as merely another way of looking at reality. Funny to think about that, in these officially more enlightened days.

Noel Coward once wrote, "I was born into a world that still took light music seriously." My own experience with what is now heaped and mashed together under the label of genre fantasy was quite similar. As a cave boy, I read a good half of the stories in this collection, and not under the covers with a flashlight, either. It was my father, a New York public school teacher and union activist, who introduced me to the work of such uncanonic writers as Algernon Blackwood, M. R. James, Lord Dunsany, George MacDonald, James Hogg, Sheridan Le Fanu, and William Austin. I've never come across another of W. W. Jacob's stories, but "The Monkey's Paw" evokes my father immediately: it was his favorite tale to tell to me and my neighborhood friends, sitting on the curb and scaring the daylights out of us, even though we'd heard it any number of times before. He may well have preferred Chekhov and Joseph Conrad for his own reading, but he never once suggested to me that it wasn't all literature.

I don't hold the least nostalgia for the elementary schools of my extinct Bronx (always excepting blessed Mrs. Margaret Butterweck, who sent me The Wind in the Willows to read when I was sick in bed), but we were given "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow," "The Happy Prince," and "The Last of the Dragons" to read before the sixth grade. In the local junior high school, which lives on in memory as Hell with training wheels, our textbooks included Poe's "The Fall of the House of Usher," Coleridge's "Kubla Khan," Walter de la Mare's "The Listeners," Dickinson's "Because I Could Not Stop for Death," and Robert Louis Stevenson's "The Bottle Imp." When a movie based on M. R. James' "Casting the Runes" appeared (a minor classic unfortunately retitled Curse of the Demon), we discussed both the film and the original story in class. Junior High 80 was not an unusual school. In any way.

The Bronx High School of Science was, which is why I came to Charlotte Gilman's "The Yellow Wallpaper" long before Gilman and her work were rediscovered by the emerging feminist movement. We were also presented (by Mrs. Mollie Epstein, as long gone as Mrs. Butterweck) with Forster's "The Celestial Omnibus," Christina Rossetti's "Goblin Market," Max Beerbohm's "Enoch Soames," Keats' "La Belle Dame sans Merci," Tennyson's "Morte d'Arthur," Yeats' poem "The Stolen Child," Hawthorne's "Young Goodman Brown," and A. E. Housman's eerie "The True Love," which began my own adolescent love affair with his stylistically stoic, stylistically limited, heart-haunting poetry. I've never really gotten over it.

I blame a person I loved very much, the editor and publisher Judy-Lynn del Rey, for the gentrification of fantastic literature. In a way, I also blame Tolkien, which is ironic, because the paperback explosion of his The Lord of the Rings trilogy in the mid-1960s set off a tidal wave of imitative "epic fantasy" that certainly swept my books along with them. Del Rey Books prompted and promoted the great majority of those "Tol-clones," as they came to he called: trilogies, almost all, and all infested with mimic elves, dwarves, wizards, dragons, enchanted rings and swords, endless Dark Lords, secretive strangers revealed to be outlaw princes...the shameless list goes ever on, long after the death of Judy-Lynn, who never confused garbage with class, and who told me in so many words that she had considerably better luck publishing the former. I read far less fantasy today than I did back when the pterodactyls were peeking over my shoulder.

The stories and poems in this book date from a time before compartmentalization took over quite as completely as it has done in our literary culture: before sequels, prequels, merchandising, movie tie-ins, and video games. (And before magical realism, which is fantasy in fancier bottles.) The majority of them are by English writers—they've been at it longer—and in most cases the really spooky stuff happens in the shadows of the reader's imagination. There is also a surprising amount of humor and satire, almost entirely absent from the current crop of clunky epics; and there is sensuality too, and the lure of the juicy deadly, as witness "Carmilla" and "Goblin Market." There's a good deal to be said—on certain occasions—for a Victorian sense of sin.

Finally, what these stories have in common is style. In our time the word has become as much of a millstone to a writer of popular fiction as liberal is to a politician. Editors constantly urge the self-fulfilling necessity of lower and lower common denominators, and one becomes wearily accustomed to going without that other sensuality of language used with grace and music—with attention—not to show off, but to invite the audience into the author's pleasure in telling a tale exactly as its nature demands it to be told; in deliberating joyously over choosing the right word and not its second cousin. To quote a modern stylist named Joni Mitchell, "you don't know what you got till it's gone."

Or until you read a book like the Treasury of the Fantastic. I really only wrote this foreword so I could get a free copy.