After a stint as an editor for Putnam Berkley and Penguin USA (which then became Penguin Putnam but that wasn't her fault), Laura Anne left New York to go freelance in 2004. It's a decision she sometimes second-guesses, but never regrets.

Her books have been hailed as "a true American myth" by NPR, and praised for her "deft plotting and first-class characters" by Publishers Weekly. Her work includes the Devil's West trilogy, the Cosa Nostradamus urban fantasy series, the Huntsmen novels, and several story collections, most recently West Winds' Fool And Other Stories. Her Patreon also spawned the non-fiction collections, I have Strong Opinions and I Have (More) Strong Opinions.

Laura Anne's tagline alternates between "Writer, Editor, Tired Person" and "Powered by Caffeine." She lives in Seattle with a cat, a dog, and many deadlines.

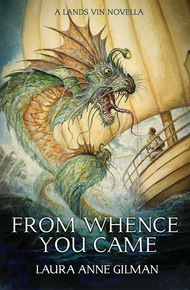

In a land where magic grows from the land, vine-mage Bradhai wanted only to tend his vineyards, craft his magic, and be left alone. Instead, the need of desperate sailors faced with unstoppable monsters takes him from his vineyards, onto the wild seas... and into history. Set in the world of the Nebula-nominated Vineart War trilogy.

"A thoughtful examination of the consequences of magic; stands alone and away from its progenitor series well. Getting to see a legendary hero as a real and flawed person is a strong technique, and the author takes full advantage of that….."

– SF SignalBradhai strode forward into the vineyard, his wide-shouldered form easily identifiable among the slaves, even though he wore the same rough-cloth shirt and trousers as they. Everything seemed to pause in the moment, slaves and vines alike, as he scanned the yard, taking in knot-and-staves of vines rising across the hillside, the bodies kneeling beside them, clippers and ties at their belts. His gaze missed nothing, decades of experience telling him where something was wrong and needed correcting.

"Easy does it, boys," he told the slaves nearest him, his voice carrying to others further away. "Easy does it. We're not in a race, we're taking it slow and steady."

He rested a hand on the shoulder of one boy, easing him away before reaching down to tuck the offending branch into place with a practiced move. "There. See?"

The slave, unable to meet his master's eyes or even look into his face, nodded. Then, when the Vineart showed no signs of walking away, reached out —slowly, carefully — to do the same with the next branch as his companions waited, silently willing the master to not notice them.

Once assured that the slave had understood the lesson, Bradhai moved on, walking a careful path through the clumped vines, his gaze moving over the yard with a practiced slide, picking out the worker who was having trouble, or doing it wrong, without being distracted by the slow, steady movements of those doing it right.

Pruning the vines was brutal, backbreaking work, on your knees and reaching up. Each spring it took even experienced slaves a day or two to recover the rhythm. But they would; by the time harvest came, they would work like smoothly-oiled wheels and gears.

He had enough slaves to deal with the work; as master, he did not have to be out here himself. And yet, it was a beautiful day, the sky clear blue, the sun bright and the air still cool, and there would be enough days he would not be able to escape his workroom: better to take advantage now.

He stopped and frowned at one clumping. There were two slaves attending it, carefully removing one fruit for every five, dropping them into the sack at their feet. The unripe fruit would go to his cook, who would make verjus, and the remains would be pitched into the backstack behind the barn, to decay into soil for the next year's garden. The business of the vintner might be spellwine, but nothing could be wasted.

Waste. He stared at the clump of vines.

"Don't bother, boys," he said. "Strip them all."

"Master?"

The first slave was one of his elders; he had inherited him from his own master, which meant the boy was no boy any more. Bradhai made note to have him taken from field work after this year's Harvest, and put to doing something more suited to his age.

"Strip them all for the kitchen, mark it for removal." There was no sense of magic in those vines, no touch of the Root in them. Therefore, they were useless. He would have the space replanted with vines that still produced.

"Yes, master." The second slave, new to the field, stared at him with wide dark eyes until the older one shoved him with an open hand and sent him back to work. Bradhai moved on.