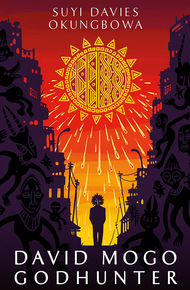

Suyi Davis Okungbowa is a storyteller who writes from Lagos, Nigeria. His stories have been published in Fireside, PodCastle, The Dark, StarShipSofa, Mothership Zeta, Omenana, and other places. Suyi has worked in engineering and financial audit, and now works in brand marketing, where he gets paid to tell stories. He is also associate editor at Podcastle and a charter member of the African Speculative Fiction Society.

LAGOS WILL NOT BE DESTROYED

The gods have fallen to earth in their thousands, and chaos reigns.

Though broken and leaderless, the city endures.

David Mogo, demigod and godhunter, has one task: capture two of the most powerful gods in the city and deliver them to the wizard gangster Lukmon Ajala.

No problem, right?

"A riveting deubt…captivating. Readers who enjoy non-Western fantasy, mythpunk, and tales of found family will find it delightful."

– Publishers Weekly"From its title to its plot to its terse but vivid prose…what follows is assured and arch, unsettling and thoroughly enjoyable — an auspicious debut from one of the most promising new voices in the coterie of African SFF Writers."

– WIRED"Vivid, visceral and with a strength of the voice that just pulls me right in. The god-littered world of David Mogo's Lagos just won't let go."

– Jeannette Ng, author of Under the Pendulum SunTHIS IS GOING to be a bad job.

I know it from the angular smile of the wizard-ruler seated before me. I know it because I should sense the icy heat of his godessence on my collarbone, but feel absolutely nothing. I know it because right outside this handcrafted palace, the rest of Lagos mainland is a dank, brooding, perilous hog pen; yet this foyer smells like orange air freshener, and you can only ignore the stink of your own shit for so long.

Let's start with how my new client remains the Baálẹ̀ of the long-abandoned Agbado community, retaining his palace right past the slum's railway crossing. From the outside looking in, you'd never picture such a sophisticated interior. I'm seated in a soft couch under ceiling lights. Ceiling lights oh, not hanging bulbs. D'you know when last anyone was able to get ordinary power in Lagos? Papa Udi and I haven't seen a blink of power in our house since The Falling over a decade ago. We run a 650VA Yamaha generator for three hours every day; just enough to charge our phones and watch the evening news.

But here, Lukmon Ajala has everything. There's a minibar and coffee-maker in the far end of the reception where I'm sitting. The floor-to-ceiling glass windows show halogen lamps piercing the night outside. But it's the silent thrum of a large 30KVA generator that really tells me this guy is mad wadded and true royalty.

The white babariga he wears is layered with exquisite gold embroidery. I almost burst into laughter when I first saw it. Anyone who lives in nowadays Lagos knows he can't step outside this compound in that shit; the streets out there are grimier than a mechanic's workshop. This babariga belongs in Upper Island. Little wonder he has this many aides and guards.

It's not just his clothes. His perfume is exquisite too, the kind that invites you to inhale rather than makes you sneeze. He wears a fìlà that's half embroidered headpiece, half regular cap, and a tiny smattering of greying hair peeks out from underneath, even though he's young—fiftyish. His eyes are white and piercing. He watches me with them now, smooth hands folded over each other in astute calm.

"So, three million naira on delivery," he says. "If you think about it, that's one-point-five-mil per god."

Yes. Lukmon Ajala One, Baálẹ̀ of Agbado, wants me to go to the epicentre of The Falling and find Ibeji, the twin orishas—high gods. He wants me to capture them both and bring them to him.

"Why not just send your men?" I gesture about at his security detail, a 70/30 split between sergeants hired from the Nigerian Police Force and local hired hands. The policemen mostly run outdoor detail and convoy security, hoisting worn rifles; the meathead boys are mostly palace hands. The three in front of us now, one at each entrance, wear placid faces and carry no visible weapons; but visible beneath the sleeves of their bicep-hugging t-shirts are written wards, like henna tattoos.

He smiles. "This boy, you just want me to massage your ego." He sits forward. "We both know I'm hiring you because you're no ordinary man. You handle these things everyday, and I've been told you have quick turnaround. I also hear you're more skilled in hand-to-hand than all my men."

"And you, sir, are the most powerful practitioner this side of Lagos," I say. "It won't be difficult for you to prepare something and give them to do this job. Or even better, go yourself."

He laughs and fingers his babariga. "You think this atiku was made for tussling with gods at Èkó?"

I shrug.

He snorts. "The way you're behaving, somebody would think you don't need this money."

He obviously does his homework; I can't even start with what three mil will do for my current situation. What's worrisome is how Ajala knows it. It couldn't have been Papa Udi—he won't touch this man with a stick. This is the first thing wrong with this job.

Second thing: I just can't get over that twinkle in his eye when we talk about Ibeji.

A woman, likely one of Ajala's wives, comes and kneels beside him, setting a small bag by his feet. He pats her on the shoulder, and she bows, rises and scuttles off. Not for one second does she take her eyes off the floor.

"Look sir," I say, "my work is simple housekeeping: godlings lose their way and make home in people's garages or pawpaw trees, and I chase them out. I don't capture anything, not to talk of a high god."

"High gods. And that one is not a problem." He opens the bag, pulls out a squat, iridescent vial with a stopper and a small, carved ceremonial mask and lays them on the coffee table between us. He points to the flask. "This is a Spirit Bottle, made from Yasal crystals. A Santeria priest gifted it to me when I visited Brazil. All you need to do is ensure Ibeji don't stray too far from their centre and materialise. Then you trap them."

"How will I see them if they're dematerialised?"

"That's why you need this," he says, pointing to the mask. "This is emi boju."

A spirit mask. I don't speak Yoruba, but I understand it well enough.

"I need those gods, Mr Mogo," Ajala says.

I don't like his smile. I don't like it at all.

"What're you going to do with them?"

Now he frowns. Something flashes across his face, hard and pulsing, then he breaks it with an icewater chuckle. For a moment, I'm reminded this man is a wizard; he not only carries a good enough dose of godessence in him to cause some harm, but is also twice as knowledgeable about the practice as Papa Udi. He's not to be toyed with.

"I thought you had a don't ask policy with your customers?"

"Not if they're hiring me to kidnap gods."

"It's not kidnapping, Mr Mogo," he says. "Think of it as borrowing."

Borrowing gods. Makes no sense.

"Sir, you know what?" I rise and smooth down my t-shirt and jeans. "How about I think about it and get back to you tomorrow?"

"Ah." He rises with me. "To confer with your pa?"

I chuckle. Confer, indeed. Papa Udi can't even know I came here.

Ajala laughs. "Wizards. We never like each other. Remove our code of practice, and we'd have finished each other since." The way he says it, it sounds like I would've finished everyone off since. He has that glint in his eye again.

He picks up the bottle and mask, places them back in the bag, then hands the bag to me.

"I'll get them when I make my decision," I say.

"Of course," he says, not withdrawing the bag. "I'm confident you'll make the right choice."

I take the bag from him. When my hand brushes his, his fingers are cold, like a corpse's. The thought makes me shiver, and when a demigod shivers, you know what that means.