Justina Robson has published quite a few novels and short stories. Many have been shortlisted for awards and she was the winner of the 2000 Amazon Writers' Bursary. In addition to her original works she is the proud author of The Covenant of Primus (47 North, 2013) – the Hasbro-authorised history and 'bible' of The Transformers.

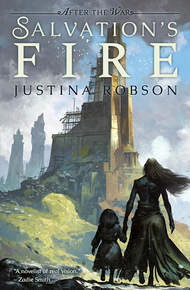

Her most recent novels are Salvation's Fire, a fantasy (Solaris, 2018), and The Tales of Catt and Fisher (Solaris, 2020). She has a new collection, Our Savage Heart, due out from NewCon Press later this year.

Her stories range widely over SF and Fantasy, often featuring AIs and machines who aren't exactly what they seem.

The Tzarkomen necromancers sacrificed a thousand women to create a Bride for the Kinslayer so he would spare them in the war. But the Kinslayer is dead and now the creation intended to ensure his eternal rule lies abandoned by its makers in the last place in the world that anyone would look for it.

Which doesn't prevent someone finding her by accident.

Will the Bride return the gods to the world or will she bring the end of days? It all depends on the one who found her, Kula, a broken-hearted little girl with nothing left to lose.

"This is a clever, vivid, cunningly crafted work of fantasy, one which moves from the personal to the epic and back with swift, assured prose."

– SandF Reviews"Robson handled the intricacies and mythology of this world extremely well"

– Irregular Fiction"Not only is it an interesting successor to the first, which was one of my favorite surprises this year, but it expands and refracts a lot of the ideas of Redemption's Blade in powerful ways."

– Amazon Review"The characters are rich and strange, the situations imaginative and engaging, the overall impression layered, thoughtful, and overall beautiful."

– Amazon ReviewTHE GIRL WAS lost. Everyone was lost at the camp. It was a place for lost things: people, dogs, things carried and loved, things carried and hated, things without homes or names. They were put down there because there was nowhere else to be put down, on a land that nobody had cared about enough to set a spade in or fence around. It wasn't bad land, but it had no particular goodness. Water was far. Trees were sparse. Grass was tough and unlovely to behold. Weed and brambles were endless, hiding the little game. Even the sky was meagre, eked across the hills like a hide stretched too thin which would soon get hard in the rain, and tear, and let everything pour in.

The girl shared a tent with two angry women. They were not relatives but they had a wider kinship that marked them both as Babohendra, the people of the horse. They were further displaced than she was and their semi-circular hoofs, angled legs and furred skins of chestnut and black were foreign enough to be frightening, though none of them had the energy for fright. The Kinslayer's armies had seen to that. All of them were exhausted, worn down to the bones by running. Even after the turn of the seasons had thrice counted them in they were always light sleepers, ready to leave, unable to believe that it was over.

Perhaps it was not over. She wasn't sure. She'd felt him die. A life like that was distinctive, even at a great distance. It had left behind a kind of silence that resonated against all he had touched that still lived. She knew he was a monster, a death-bringer of unmatched carnage, even among his own kind, but she had seen him as a vivid, vibrant exultation of life right until the last moments of his rending. As a life he had been exceptional and the music of the world was less without him. But without his smothering presence she was able to detect other melodies—the brilliant shapes of other Guardians still active—and so she alone of all the sad rabble in that place was completely confident that he was gone, his armies scattered, his plans awry, his destiny reached and story ended.

He had wanted to end her story but he had missed her. She smiled when she thought of this. It was her secret gladness and it gave her the power to endure hunger, thirst, cold and starvation of love. He had lost and she was still alive. But she was alone. Her smile faded then, always, as she knew it. None of these people were her people. Their kind no longer existed upon the earth.

This day, grey and damp, filled with lamenting from one quarter, with glum despair at others, was no different to a hundred other days. The sun had come up, those who were able had gone to hunt and forage, those who were not remained by the smoky little fires and made teas from sticks. A party went out to find out what happened to the last group who had set off to a village some twenty miles distant and not returned. They went armed with sharpened poles, slowly, hoping to be met on the way. Without some kind of trade they were going to die soon in this nothing valley, surrounded by indifferent woodlands, as surely as rabbits in a trap. They had nothing to trade but themselves and a few little trinkets that were precious but of no value to a stranger. There was nothing to be done about it.

She went out of the tent and stood in the mud, watching the other children sit sullenly or poke about with sticks. They didn't like her and she didn't like them. It wasn't personal. They stared at her, sunken eyes that would have been spiteful but now were losing interest and would soon not care. The adults moved around slowly, as if they were under water. They didn't see her. She didn't belong with them. A moment after she had turned away a stone hit her on the head. Probably they were laughing at her, but maybe not. She didn't know, wouldn't give them the satisfaction of looking around to find out. It settled the matter.

She went back into the tent and picked up the rag bundle she used to gather leaves and berries. Heading out past the few log cabins she took the path towards the deeper forest at their backs. They had come this way when they first arrived and she remembered seeing roads.

A sharp jerk on her sleeve stopped her. She looked up. The younger of the two women whose tent she shared was looking, moving her mouth, making a questioning, cross face. Her hoof stamped, betraying her anxiety.

The girl pointed to the woods. Mimed picking, eating.

An expression of exasperation, sadness and concern filled the woman's long features. Her brown eyes were patient, much more so than her hands, which she folded up against the urge to snatch the girl and hold her too tightly. There was an emptiness there, the ghost of someone left behind. The girl knew it and waited until the woman nodded to say she could go. It was all she had to give as a parting gift to the one who had tried to help her, that moment of kindness. There should be so much more, but there wasn't.

She left the camp and moved beyond the briar patches and the glades of wild garlic, the fallen logs where mushrooms came, the boles of familiar trees that were climbable where there might be birds nests and insects within the reach of someone small, light. She knew them all. She touched them as she passed, those slow lives, and felt through their roots across the huge reach of the land to where there were other bright patches, people and their animals. She found a way.

She dropped the rags at some point before it got dark. She drank from a stream and left her fingers in it to go cold because there were fish there, lively and full of brilliance, that lent her a little joy. Once she looked around, looked back. She took a route through the thorn bushes that no larger person could follow, to be sure.

She traced her way safely, guided by the beating hearts of the tiny animals, the darting swiftness of the flies. She avoided humans. She kept to the path of the trees, heading to a spot far away in the West where a brilliant shadow was moving; dark candlelight, the grey, ever-flickering silver gleams of the Wanderer.