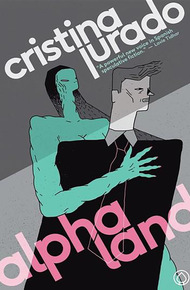

Cristina Jurado(Madrid, 1972) is a bilingual writer and the editor of SuperSonic Mag, a Spanish & Englishvenue which has re-energize the Spanish speculative fiction scene. She is the recipient of theIgnotus Prize (Spanish Hugo)for best short story ('Second Death of the Father'), best non-fiction article, and best magazine. SuperSonic Mag also won theEuropean Science Fiction Spirit of Dedication Award as best eZinein 2016. She lives in Dubai, and works for Apex Magazine as editor for fiction in translation.

Otherness is the idea that permeates all these speculative stories, full of characters troubled by the misconstruction of their identities, and in permanent search for answers in the margins of reality.

From upgraded humans to individuals living among daydreams, from monsters to fantastic beings, these creatures populate a highly imaginative and evocative world, impregnated by an inspired sense of wonder.

Cristina Jurado is one of the hardest working and most celebrated Spanish writers and editors working today in both Spanish and English. Nominated multiple times for Spain's Ignotus Award (which she's won for both writing and editing), her editorial work includes Supersonic and the anthology The Apex Book of World SF 5. Alphaland is her debut collection in English, with some stories translated from Spanish by James Womack and some written especially for the collection. – Lavie Tidhar

"A powerful new voice in Spanish speculative fiction."

– Lavie Tidhar"Jurado's fiction sometimes defies classification, but it's always stimulating, imaginative and thought-provoking. Thanks the stars that none of the quality got lost in translation. Any fan of fantastical fiction will enjoy the stories inAlphaland."

– Tade Thompson"Here is erotic cosmic dark fantasy; here is a doomed astronaut snatched from suicide in space by ... something. Here is a psychopath with her memories erased, murderously on the trail of Who, and Why? Here are very dark visceral visions—of a swamp creature upon the ceiling, of ruthless bestial battles against shadows. Here are radically 'other' stories, muscular, gritty, evocative. Here's your chance to relish what Spanish readers voted the best story of 2017. I am so impressed by this outstanding, and eloquently translated, collection."

– Ian Watson"Stories of identity, paranoia and loss that reso-nate in the mind and which will leave you both uncomfortable and entertained. Recommended for any fan of dark fiction."

– Jason Sizemore"[A] writer who plainly earned an enthusiastic audience."

– M.L. Clark, Strange Horizons review of AlphalandThe mother, a globular ship. Umbilical cords that provide food, remove waste, hydrate, keep warm, and monitor. A child safe at the centre of anectopic pregnancy, passenger in an unnatural womb made from exotic fibres, travelling through the guts of the universe at a speed hypothesised by scientists without money to investigate, and who substitute their lack of funds for imagination.

He is hanging from a wall that could be the floor, or the roof, for there is no up or down here, no left or right, no centre or periphery. Zero gravity is a blanket that wraps round him, a familiar and calming sensation that keeps his brain afloat. He feels fluids entering and leaving his body, he hears a noise, like that of water boiling, and remembers some English china cups, with hand-painted roses and gold rims, on a tablecloth decorated in brown and orange flowers. It is cold outside, and raining, but inside it is warm and welcoming, and Peggy takes the kettle off the fire and pours the steaming liquid into the cups. There is a plate of gingerbread, and as his mother pours the milk, he takes a piece and nibbles it in the hope that the tea will soon get cool enough to drink. There is an older brother and a father somewhere, but not in this memory.

The ship takes care of him, brings him the nutrition he requires, makes the relevant adjustments to his body. He feels expansions and contractions, but cannot sense where in his body they are taking place. Right now he would happily sit and take a cup of tea in the Bromley kitchen. If he makes the effort, he can taste the gingerbread in his mouth, the flavour he likes so much. There's no need to make the effort, though, because shortly after thinking of it, he feels the taste of ginger scratchy on his tongue. He licks his lips.

'Thank you, Peggy.'

He still cannot bring himself to say 'mother'.

Every time he thinks of Houston he wants to laugh and the walls laugh with him, carrying the echo of his guffaw in all directions. How much those bastards must be wishing he were retransmitting everything he saw! Control must have given him up for dead and would be writing their report about him: 'died on active service'. But he is alive, feeling better than ever, and can laugh at them from his privileged womb.

He had opened up the porthole and launched himself to the stars. You have to have balls to do that.

He would never have died on livestream, as Houston wanted, sending out his final moments to all the televisions on the planet and breaking all viewing records. 'If anything goes wrong,' they said, 'keep in the centre of the image so that we can record you.' This is entirely scientific, they never stopped saying, but the rocket was filled with products that he had to show to the camera at precisely agreed times: the Miami Gators shirt at the instant he entered nominal programmed orbit; Landa soft drinks at least three times a day; the Cosmos watch every time Houston entered into conversation with him; the AirAmericana baseball cap when the launch manoeuvres had been completed. He would bet anything you like that they would have used his death to sell insurance policies, cars, or some ersatz champagne with a Frenchified name. He imagines the Defence Department attaché rubbing his hands at this new national drama, and the GNN executives, the ones with the exclusive broadcast rights, working out what they were going to earn in advertising revenue.

He's screwed their plans up, but he feels no regret. The one who is travelling through the guts of space, a long way from Bromley, is him. The Houston crowd, with all their attachés, executives, directors, doctors and engineers, are all back home, some of them cuddling up to their wives, some of them fighting with them, and the rest ignoring them.

He is not sure—he can't be—but he thinks that he will never see Marianne again. It is one of those certainties that he has gathered over the course of his life, the kind you feel rather than think; like the sun rising in the east and setting in the west. Marianne and the bend of her naked back when he stroked her in bed. Marianne trying on clothes and looking at herself in the mirror without knowing which outfit to pick. Marianne smoking at the window, dressed in an old shirt, the rain licking the panes behind her.

Here you can't hear anything, like in a sound-proofed recording studio, but he doesn't know why he thinks of things like that; he's never been in a recording studio in his life.

He is an accidental astronaut, a British pilot who was working on supersonic planes, more for fun than out of a sense of vocation, but who was tempted by a trip over the Atlantic. One of those who was seduced by the clouds in America, which are much whiter, like American teeth; and the sky is bluer and the cars are bigger, like the egos of the people driving them. A signature on a contract, and he could start earning dollars and debt, to buy a prefab life and escape from a frozen version of England.

The silence is so deep that it seems to squeak. He hears his blood travelling through every single one of the capillaries that crisscross his body, and he thinks of the noise made by the engines of the planes he used to fly, back when he did not have tubes entering his face. He laughs again and the whole ship imitates him.