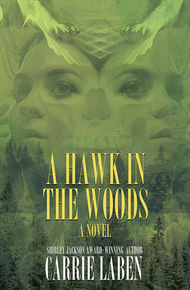

CARRIE LABEN lives in Queens, where she spends a lot of time staring at birds. Her work has appeared in such venues asBirding,Clarkesworld,The Dark,Indiana Review,Okey-Panky, andOutlook Springs. In 2017 she won the Shirley Jackson Award in Short Fiction for her story "Postcards from Natalie" and Duke University's Documentary Essay Prize for the essay "The Wrong Place". In 2015 she was selected for the Anne LaBastille Memorial Writer's Residency, in 2018 she was a MacDowell Fellow, and in 2019 she was a resident at Brush Creek. This is her first novel.

When newscaster Abby Waite is diagnosed with a potentially terminal illness, she decides to do the logical thing… break her twin sister Martha out of prison and hit the road. Their destination is the Waite family cabin in Minnesota where Abby plans a family reunion of sorts. But when you come from a family where your grandfather frequently took control of your body during your youth, where your mother tried to inhabit your mind and suck your youthful energies out of you, and where so many dark secrets–and bodies, even–are buried, such a family meeting promises to be nothing short of complicated…

Come for the twin witches on a road trip, stay for the deep dive into sisterhood, belonging, trauma, and identity. "This one pushed all my buttons," says Ross Lockhart.

"Carrie Laben is a monster—they don't even make writers like this anymore. You will be reading her name for decades to come."

– Cara Hoffman, author of Running and So Much Pretty"Consider me a fan for life."

– Paul Tremblay, author of A Head Full of GhostsAn outside observer might have thought Grandfather was suffering from grief that summer, if any outside observer had cared.

He got skinnier, more stooped; his hair and beard thinned to wisps; his skin dried. And yes, in the nonexistent outside observer's defense, he was rarely seen outside any more. His weekly trips to the library and the liquor store ended, and then his daily routine of front porch sitting dwindled to an hour, to fifteen minutes. He abdicated opportunities to supervise the mowing of the lawn and Abby and Martha's work in the garden.

But Abby knew better. He was still giving her lessons and lectures. He was still staying up til well after her bedtime, light shining through the space beneath his door when she took furtive trips to the bathroom or kitchen. He was still yelling at Mom, only to abruptly shut up when Abby or Martha made a noise that told him they'd come back into the house. He was still Grandfather. And Martha wasn't getting as many odd mean spells. Mom was out of bed and normal-ish again, yelling back at Grandfather, making Martha take off the locket and give it to her for safe-keeping, because Martha was soscatterbrained she'd just lose it in the creek. The family got so tantalizingly close to righting itself, for a few months.

As July fourth — when they always started the trip to Minnesota — approached, Abby started dropping hints to Mom about packing. Hints were a better bet than direct questions, when it came to Mom and Grandfather. Direct questions opened the door to direct refusals, and refusals, unlike permissions and promises, were never reversed later.

"Your grandfather's too sick to travel right now," Mom said, louder than necessary, and that was too close to a full-fledged 'no' for Abby's comfort.

"Why do you care so much?" Martha asked her later, when she complained about it. "You always say you're bored when we're there."

"I'm bored here, too," Abby said. Martha wouldn't understand Abby's suspicions that the change in routine was a sign, like a certain smell to the milk that wasn't expired quite yet, like a hairline fracture that meant she should let Martha wash that particular plate and get the blame when it broke.

The holiday came and went. Martha and Abby watched as distant driveways along the street filled up with cars and the sweet-smelling smoke from the barbecues drifted over them. When it got dark, they walked to the top of the neighbor's hill to watch the fireworks exploding, small and muffled, above the theme park miles away. Mom and Grandfather ignored the day, going about their normal routines so hard and so silent that it was obvious they were inches from screaming in each others' faces, even if you couldn't see the little daggers of attention stabbing out at each other and then, after a moment's application of willpower, retracting.

The morning of the fifth, Abby woke up early. In a normal year, she would have been squashed against Martha or Grandma, or at worst between both. She could read in the car without getting sick, so sometimes she took the middle before Mom or Grandfather made her, to get credit for being a good girl later. These last few years Grandma had smelled funny, though, and Martha was getting big enough to elbow Abby without meaning to when she turned to look at the horses or deer or funny signs for diners along the road.

Abby had decided that once she learned to drive, she'd never, ever put up with being a passenger again.

Now she had space, and time, and she could go read her books in the old barn if she wanted to or on the front porch where Grandfather used to sit. But she didn't. She lay in bed for a long time, half-convinced that if she just waited Mom would come along and yell at her for being lazy when she knew they needed to get packed and into the car.

No trip. No stops at Dairy Queen along the road for sundae battles, no playing cows-and-cemeteries, no slugging Martha in the arm when she spotted a Volkswagen Beetle. But that wasn't why she was upset, because those things only ended in mosquitoes and mooching around outside the cabin while Mom and Grandfather worked on whatever it was they were working on. She was upset because the feeling like a bad milk smell was worse than ever.

She sat up, swung her legs out of bed. She was going to find Martha, and they were going to go catch newts all day. Out of sight, out of mind, whatever was going on that was safest.

Abby went downstairs, and to her surprise found the ground floor silent and empty. She glanced out the window, and the car was gone, and for a moment she had a pang — but no, a roast was thawing on the kitchen counter, they hadn't gone far. Someone was probably around. Certainly Martha, Mom never took her anywhere that she didn't also take Abby, and probably Grandfather behind the closed door of his always-shadowed bedroom. He was just keeping quiet.

Martha wasn't in the apple orchard. She wasn't in the garden shed. She wasn't in the big hayloft or the stalls in the old barn, which wasn't surprising — Martha hated the bloodstained floors and even though Mom and Grandfather said it was impossible, that animals didn't work like that, she insisted that she could hear the long-gone pigs and cows crying in fear.

It was impossible that Abby was hearing them now, too. She'd never heard them before. They were faint, but there were sounds of pain. She held her breath and tried to be too still to make her own noise, closed her eyes against the distraction of shadows and dust motes, and turned slowly in a circle as she tried to figure out where the sounds were coming from.

Northeast. The little grain shed built right up against the far wall. She moved towards it with short one-at-a-time steps, to stay quiet of course and not because she was afraid. The moaning never broke, but she was almost sure that there was only one of — of whatever was making the noise. She couldn't tell if it was human or not. It wasn't Martha's ghost pigs, she knew that, even though she'd never heard a pig in real life. Something alive was making that sound. Something alive and in pain. Something that still had a will, and wanted to get out.

The grain-shed door was closed, but the old, dry wood was full of knotholes and cracks she could peek through. For a moment she imagined a claw poking back to put out her eye, but she shook her head and made herself lean down. That was horror movies, not real life.

They hadn't kept grain in the grain shed since Mom was a little girl, but there were still a few old empty sacks scattered around, draped over bins, undisturbed for decades because the mice never came. Now the sacks had been pulled down and used to cover the moaning thing from head to foot, without a gap. If not for the moaning she would not have known it was alive—any movement it made was too slight to be sure of in the dusty, dim light from one small dirty window.

It could be a trick, she thought. It might not be weak at all. If I go inside, it could turn on me.

There was a pitchfork near the barn door, and she backed up in her own footsteps until she was able to reach behind her and grasp it. It was heavy, and when she tried to hold it out in front of her the tines wobbled loose on the handle, so she held it at her side where it might look more intimidating.

The moaning finally stopped as she dragged the door of the grain shed open. The bags stirred and slid away as the moaning thing reached out a hand and tried to lift its head.

It might have looked like Grandfather, if something had hollowed out Grandfather's bones and sucked the flesh from beneath his skin and somehow rusted away his will to a few weak, quivering strands. Even then, though, Abby couldn't believe that Grandfather would ever make that high, whimpering moan she'd heard. This wasn't Grandfather. It couldn't be.

She'd pointed her pitchfork at it without thinking, and it had lifted its head enough to see that she was armed. Even so, the wisps of intent focused on her. "Help," it said, still in a whiny treble. "Help me, Abby."

She wanted to step forward. She wanted to back away. She just stared at it.

"Please," it said. "It's me, it's Martha. Help me."

Abby dropped the pitchfork and ran, slamming the door behind her, not stopping until she was out of the barn and on the other side of the house in the bright sunlight.

Whatever it was, it knew her weaknesses.