Milo Behr grew up in New York, Central America, Europe and the Middle East. His short-form fiction has appeared in the MechMuse Anthology alongside David Farland, Kevin J. Anderson, Eugie Foster, and others. He is an entertainment technologist, musician and writer. He has published academically through IEEE and others, and spoken at SIGGRAPH, BIA/Kelsey's ILM, VFX and elsewhere. Milo's work has been recognized by the Gartner Group as among the "most visionary" in information security, and he has twice been commended by the US Army for outstanding research. He invented Cryptocast streaming encryption, DigiClay Animation and a variety of other technologies.

Milo's education is in music. He is a classically-trained countertenor, singing the works of Bach, Händel, Monteverdi, Babbitt, Britten and others.

Milo lives among the Rocky Mountains with his wife and three children.

Welcome, he says, to the "fabulous fabulous" Lawrence Booth show. His flamboyance is well-practiced. They all know him, he's world-renowned (he reminds them). Then he calls them the faceless masses, says he doesn't care who they are. It's a familiar deadpan, his particular brand of sensationalism through effrontery. Then he gets more personal, but it isn't sincere—how could it be? I'll be your guide, he says, your mentor, your guru, your spiritual advisor, leading you along the "sordid paths of the sublime, the seedy, and the sensational." And it's true, he will be.

This is Lawrence Booth, host of a 22nd-century variety show; an ultimate evolution of vaudeville; a tangible expression of social media and a venue for the people's justice. And his favorite toy is a superhero—a popular bounty hunter called Beowulf.

When New York's paragons turn to violent crime, it falls to Booth and Beowulf to restore order (and, more importantly, to make a good show of it). Is this an unraveling of the social fabric? Have our leaders turned, as parasites on a host? Or are they victims themselves of a society dependent on the wonders—and the dangers—of high technology?

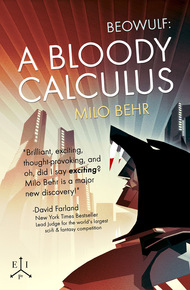

BEOWULF: A BLOODY CALCULUS, is a frenetic exploration of logical extremes. It's about superheroes as the products of marketing machines, social media as a fundamental and frightening social adhesive, summary justice as a Utilitarian exigency. It's part mystery, part thriller, all in the plugged-in context of a cyberpunk future.

And it's one a helluva ride.

"Over the past 20 years I've discovered dozens of authors who have gone on to become New York Times bestsellers, and I've learned to recognize genius when I see it.

In BEOWULF: A BLOODY CALCULUS, the genius is apparent from page one. You see, I look for a number of things in a writing sample: a powerful story concept, an engaging narrative, artistry in the prose, and an author with a powerful mind. Too often, a new author will fail at some level: but not Milo Behr. From page one, it was obvious that this is a rare and unique talent. Very often I will find tales with sophisticated artistry but which are intellectually barren. Or I will find genuine genius devoid of beauty.

This author shows both a deep artistry in his work AND intellectual genius. From the staccato rhythms created in the opening lines to the reinvention of rules for punctuation, one can see instantly that this is a writer who keenly hears and feels the music in his words, yet there is nothing lacking in his content. Whether he's commenting on modern media, taking-on political ideologies, or wrestling with moral complexities, there is a delightful depth to Milo Behr's work.

Yet the story never stagnates, never bogs down. Instead its a seamless fusion of virtuosity and insight. As I read, I kept thinking, "If William Wordsworth were alive today and writing cyberpunk, this is what he might write."

He would strive to write something that was beautiful, profound, and ultimately affirming. There is something about Milo Behr's work that is at once contemporary yet iconic.

I invite you to read it, and see if you love it as much as I do."

"Behr’s Beowulf: A Bloody Calculus is a work that demands I take a moment to comment.

First, it succeeds on many levels. Immediately, it is utterly readable while still being impressive as ‘literature’, which is something rare and important. It manages this by pushing forward at a brisk pace, never getting mired in its own profundity — never seeming concerned it will run out of ideas, insights, or momentum. Like all great works, it manages to be great without trying to be brilliant. It just is, and effortlessly so.

Most fascinating to me as a composer was the way Behr deconstructed the idea of an epic poem in a fresh, contemporary, and courageous treatment. I am not sure what a literary academic would say, but Behr's Beowulf is a distinct form of what I can best describe as deconstructed poetry that pays homage to its roots while being true to itself as a futuristic telling. For those averse to poetry, the style will not be off-putting — you will perceive it as prose, but prose whose rhythm is sophisticated in its subdivisions of time and its impeccable sense of proportion and pace. It does not plod, nor does it pound home perpetual repetitions of stress and repose. It is dynamic, complex, and it’s very hard to pin down exactly why it works as it does.

Finally, the way in which he breaks rules of grammar in order to achieve a concrete creative objective is a worthy lesson for creatives of any discipline about how and when rules can and should be broken. This consistency of honed purpose paired with the worthiness (and fun) of the subject matter and the depth of the author’s insight catapult this work into my permanent library, and demand the time it took to write a thoughtful review, which is not something I often do."

Welcome, he says, to the "fabulous fabulous" Lawrence Booth show. His flamboyance is well-practiced. He makes the expected references to ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, one and all. They all know him, he's world-renowned (he reminds them). Then he calls them the faceless masses, says he doesn't care who they are. It's a familiar deadpan, his particular brand of sensationalism through effrontery. Then he gets more personal, but it isn't sincere—how could it be? I'll be your guide, he says, your mentor, your guru, your spiritual advisor, leading you along the "sordid paths of the sublime, the seedy, and the sensational." And it's true, he will be. It's an exciting show tonight, he says, "thrilling, even."

"Engrossing," says a short, bald man sitting with the band. That's Randy.

"Thank you, Randy," says Lawrence Booth. He throws one arm wide, and a picture-in-picture panel appears beneath the sweep of his tailored sleeve. It sparkles like it's made of pixie dust. On it, a chromed grotesquery rears: a glimmering bear's head with mouth open in a savage snarl, metallic teeth menacing, and eyes glowing an unsettling sapphire blue. It's just a man, but he's wearing a sculpted helmet: it's one hell of an affectation.

You know him, says Booth, you love him, you come here to see him. "New York's most celebrated bounty hunter, our very own valorous vigilante, empowered by the people of this great city to be the enforcing hand of its tough love." He doesn't say: and most importantly, he's fun to watch. Then he makes a flourish with his hands and gestures to "the unforgettable, the irrepressible, the ever-indomitable Beowulf."

Randy beats three times on his snare, head bobbing in rhythm, before the band strikes up behind him. It's a melodramatic riff, all crashing drums and wailing guitar. Through the air, brilliant cords of colored light trace frenetically like living streamers. They are suitably impressive, undulating and pulsing, casting a rainbow glow over the hall, and its tasteless neo-rococo frills. It's an enormous space, a cavernous "temple to the populous god of horde hysteria," Booth often says in private. The hall's rear is lost in shadow and distance. Throngs of millions beat fists in the air in tempo with the music, and scream unintelligible glee. Lawrence Booth himself pumps his chin in time with the music, and casts a casual glance over the mobs beneath him. His three-piece tailored suit shimmers in hues of opalescent green and purple. His white shirt is smartly pressed, with a fashionable, wide collar. His double-Windsor knot is old fashioned, but he prefers it; the tie is bright yellow. A high wave of stark-white hair is sculpted above an impossibly handsome face. His chiseled features and bronze complexion frame striking violet eyes. He swivels one way in his chair, then the other, and then spins a full circle before coming to a stop. He wears his exaggerated grin like a mask, perfect, white teeth gleaming.

But none of it's real. The entire milieu (Booth often calls it that), is a rigorous fabrication. Lawrence Booth is in reality reclined in an armchair, comfortably, within his 5th Ave. penthouse. Randy and the band aren't even in New York. And the writhing masses are tapped-in wherever they happen to be: at home; at work; some of them are even sleeping, plugged-in through dream bridges. Most of them are fans and regular viewers, but some are just passing through, on one quest or another within a thousand different intersecting massively-multiplayer games. They don't care what's real or what isn't. Or what's in-between.

Booth continues, shouting the name Beowulf over and over. We don't just report the news, he says, on the Lawrence Booth Show, we make the news. Here, and only here, you live the action. Our follow-cams are "exclusive." (There are others, of course, but they're unlicensed, and they won't have the best bits. Beowulf belongs to Booth.) He smiles, crookedly. "Nǐ de shūshì qū wài fāshēng de yīqiè měihǎo de shìwùi," he says. It's Chinese. It more or less means, "all good things happen outside your comfort zone," but there's no need to translate. He goes on, and says you can watch the news anywhere, but you come here to be a part of it. "And tonight, by god, we've got a real shocker for you."

"Chùmùjīngxīn, a shocker," agrees Randy. The band's final chord echoes through the virtual hall. "A doozy, even."

Booth arches an eyebrow and gives Randy a look. Everyone knows what that means; everyone except Randy. But he doubles down. "A doozy. A fu**ing doozy." Censors bleep the audio for younger viewers on the General Audience feed. But there are others: the Justice Observer and Mature Audience 'casts are untouched.

"You're a man trapped in the wrong century," says Booth. He smiles tolerantly. Everyone knows what that means, too. Randy has one hell of a band, but that's where his genius ends. Booth keeps him around, partly as a contrast to his own easy rapport. If Randy's a little gauche, it only makes Booth look better by comparison.

Booth lets his smile drop, and looks mournfully out at the crowd. A silver tuba, of all things, materializes in Randy's lap. He strikes up the funereal plodding of a dies irae from a centuries-old Berlioz.

We build our lives, says Booth, around behavioral expectations and psychological macros. He calls them stereotypes. "Optimal? No. Necessary? Absolutely." They are the templates that allow us to function moment-to-moment without "constantly engaging the high-effort mental machinery of ethical and existential decision-making." He likes to sound smart—but it's not an act. Today, he says, one of those templates will fall, making all our lives just a little more complicated. The tuba fades to silence, and a mass of violins—played by a single man in the band—take up an abrasive ostinato. "We've come to tolerate, even expect violence . . . from prescribed sources," he says. "We've braced ourselves against it, conditioned ourselves to avoid it, not to see it." But today . . . "Today we face a truth. Not a new truth, but a singularly uncomfortable one. Violence can come from anywhere. Madness knows no prejudice." He's proud of that bit—he wrote it himself. His writers didn't touch it.

Booth's picture-in-picture grows to engulf the stage, and video from the follow-cams appears. It's a cafeteria. The living have fled, but three-dozen-odd corpses litter the ground and slump over tables and chairs. Blood is smeared across grey flagstones, and pooled on tabletops around a varied flotsam of plates, utensils, overturned drinks and half-eaten food. A fire alarm blares, and red lights pulse. The follow-cams move in, beetle-sized quadracopters, small and agile, fearless. One of them hovers over a table, panning across the blue-uniformed bodies collapsed around it. The footage shines vividly on the picture-in-picture, but most viewers have "jumped" right into the cams, and see the scene as if they were there, with a fully immersive view.

A hush comes over the crowd. Reverence, even from this lot of commotion-hungry thrill-seekers. It isn't the sight of it—they've all seen worse in the varied virtual worlds of their gaming. But there's something primally disquieting in knowing it's real. (This had been the stuff of sociology studies for a century. All the old arguments masquerade as new ones. The causal connection between violent virtual games and real-world ferity is still tenuous, and still self-evident.)

Booth continues, but even affecting his most wretched inflection, his voice is a jarring incongruence against this charnel imagery. "The victims are the first surprise," he says softly. He shakes his head and wears a tragic frown, but no one is looking at him. "A real-world predator-turned-prey tableau. The New York Metro South-east offices; they house the 152nd police precinct. The cafeteria serves the greater office complex, police officers, bureaucrats, some elected officials. Over half the dead are NYPD."

A follow-cam zooms in on the empty holsters of the fallen men-in-blue. Booth frowns, then says, "Let's check-in with our man on the ground."

The picture-in-picture cuts to video of a large figure, crouched with his back against a low partition. He's heavily muscled and covered in form-fitting armor: distressed leather over alternating layers of visco-elastic polymers and graphene film. A pair of chromed pectoral plates glistens on his chest, matching the sheen of a helmet shaped like a bear's head, its maw open and menacing above the man's own face, with sapphire eyes glowing. This is Beowulf.

"What's the situation?" asks Booth.

"The situation is fu**ed," says Beowulf. He smiles savagely. Single shooter, he says. "Tossed a homemade explosive into the security checkpoint, then waltzed in here with guns blazing. Real piece a' work. Probably thirty dead. Maybe twenty of 'em cops. He's got a hostage, now."

"We see empty holsters on the dead," says Booth. "Why were the victims unarmed?"

Beowulf cocks his head. "Gun-free city, don'cha'know?"

Booth says: if only the perp had realized. But he doesn't mean it like that, or not entirely anyway. Everyone knows he hates guns. (It's mostly true, but he has to say that. With a show like his, he walks a political tightrope. He can't afford to alienate either half of his audience.) His mouth twists sardonically. "But the NYPD. Why weren't they armed?"

Beowulf shakes his head. "Ain't it just their bad luck? Perp hits the only precinct in town where guns aren't allowed inside." Beowulf does mean it like that. Luck had nothing to do with it. "The building has a handful of city offices. No weapons in city offices. So says the law. All weapons are checked-in to the armory."

Beowulf, says Booth, this seems an unlikely call for a bounty hunter. It's true. "Why aren't the NYPD handling it?"

"Well," says Beowulf, rubbing his chin, "we're all doing what we can. I wasn't called in. Just happened to be here. Renewing my license." Timing is all.

Booth opens his mouth, stops, closes it again, and furrows his brow. Beowulf, he says after a pause. "Are you . . . are you unarmed?"

Beowulf smiles darkly. "I am. Checked my weapon into the armory like everyone else. Perp blew it to hell. Nobody here's got anything that goes bang."

Booth pushes his arms straight, palms down on his desk, sitting up in his chair. Time to shine. He loves these speeches. He'd spin this 'round and 'round—people hanging on his every word—building the tension until nerves where ready to snap. Ladies and gentlemen, he starts portentously, we have an unprecedented situation. "Nearly twenty officers dead. Never before in my considerable career have I seen . . . "

Beowulf cuts him off. "Stow that sh*t, Booth. I've got it handled. But get a look at the perp. The kids at home'll get a kick out of him. And I need my execution warrant." He frowns. Rules are rules.

Booth smiles thinly. So they are, he says. On to the next surprise, then, by all means. "Only the most scintillating, the most unexpected here on the Lawrence Booth Show." The picture-in-picture cuts to another follow-cam, hovering in front of a grandfatherly looking man with one arm around the neck of a terrified woman, sweat making her dark skin slick, and her pink lips trembling.

A .45 caliber projectile handgun is pressed against her temple, with a pink, 3D-printed, homemade magazine extending out the bottom—it probably holds a hundred rounds. The old man wears a well-ironed Italia-arabian black suit jacket over a silk maroon shirt. A stiff white Roman collar wraps around his neck.

"That's right," says Beowulf. "He's a priest."

A collective gasp erupts from the crowd (along with more than a few jeers, and a single maniacal cackle—some look-at-me iconoclast making his mark).

And not just any priest, adds Booth. The Right Rev. John St. George Matheson, Bishop of the Unified Evangelical Episcopal Diocese of New York.

"That a fact?" asks Beowulf. "Bishop a' the Luthcopals. Prestigious company. I'll watch my language." A nervous chuckle from the crowd, a mass of staccato murmurs swelling like a wave crashing onto a pebbled beach. And a lone expletive (the same asshole as before, too eager by half to throw in with any mockery of a holy man).

"So how 'bout that warrant?" presses Beowulf.

Instantly, a clutter of information appears over the video feed. Stacks of photos, video clips and background data, all accessible to anyone watching.

"And here it is, citizens of New York," says Booth. Your evidence. A landmark decision—you won't want to miss it, etc. etc. This is a story you'll tell your grandkids, tell them how you rid the city of the "Devil in the White Collar." It's Booth's usual fare. Then on to the provisos: of course, if you aren't duly licensed, or you aren't on the Justice Observer feed, then you're outa' luck. "Stay outa' the way." Booth smiles winningly.

Randy and the band play a plodding melody, like slowly advancing hands on an old analog clock.

Booth nods and drums his fingers on his desk, then makes a flourish with his hand. "And there it is, the jury is full. We're ready to go. Thirty seconds to polling, people. Review the evidence, and weigh in. And remember, if your vote diverges from the majority's, your ranking will plummet. So vote fast, but vote smart, or next time you'll get bounced." The Booth sitting in the 5th-Ave. armchair isn't really saying this: it's a recorded macro.

A countdown glows ominously over the video feed. Booth looks down, making a show of rifling through sheets of paper newly materialized on his desk, reviewing the evidence for himself (and it is for show; the real Booth sees the data on his retinal HUD, and a series of plexiglass sheets suspended above his armchair).

Beneath the countdown, a mass of red dots gradually turns green as votes are cast. When the countdown reaches zero, all votes are green and Booth looks up. But now, he wears a white toga, and a laurel wreath perches regally on his head. It's a cheap gesture: self-deprecating and self-aware, a show that the parallels have not gone unnoticed. He extends an arm, fingers balled into a fist.

"We have a decision," he says. The good people of New York have spoken. Swift and fair justice. A drumroll from the band. Booth extends a thumb laterally. The audience holds its collective breath, waiting to see if it goes up, or down. A cymbal crash, and Booth's thumb turns downward.

Randy's tuba re-materializes, and the dies irae reprises ominously.

"Beowulf," barks Booth. "You have your warrant. Execution is authorized."

Beowulf grunts. He jerks his head over one shoulder, in the direction of the bishop. "Check out that grin," he says. "This guy isn't afraid. He's a 12-year-old looking up a lady's skirt." Sure enough, the priest's smile splits his face. He's getting a thrill out of this, and not even a naughty one. To him, this is all just good, clean fun.

"Hey, Johnny," yells Beowulf. "How's it going over there?"

An awkward pause. Then the priest yells, "I've got a hostage," like he's saying: I just had my first taste of bourbon.

"Oh, well," says Beowulf back, friendly-like. "Hostages are no fun at all. They just piss their pants. And if you shoot 'em, then they're dead, and no good for sh*t." A long beat of silence. "Can't . . . can't you smell that?" He winks at the camera.

"No," says the bishop. "Well, maybe. Awe, sick."

"Plus, if you shoot her, you'll still have to face me. Only I'll be pissed as hell. Tell you what. You let her go, and none of these nice police officers will do a thing to you. It'll be just you and me."

"You and me," says the priest. "Like a boss? You're the boss I have to kill?"

Beowulf frowns and shrugs at the camera. He says: sure, I'm the boss you have to kill, but I have a berserking skill that's triggered by dead hostages.

The priest pushes the woman away from him. She sobs, then scurries off, and out a door.

"I can't believe that worked," says Beowulf. "Gives me an idea, though." He looks to his right, then cranes his neck to look up. The hostage is free, but Beowulf's got nothing; he needs a weapon, or a plan. Preferably both.

Ah, he says with a grim smile. Face back to the camera, he nods. "I'm ready to make a move." His arm shoots up, then comes back gripping a lunch tray smeared with mustard. A stack of the things sits above him on a countertop, next to a pair of recyclers. Beowulf jumps to his feet. He's impressively fast, like an uncoiling snake.

He spins, then hurls the tray toward the priest. But its flat spin is imperfect, its lip wanders up. It flaps into a limp wobble. It flies wide and short of the priest, who lifts the muzzle of his gun to squeeze off a half-dozen automatic rounds at it. A boyish smile lights his face. No hatred, no anger. Just juvenile joy at a challenge.

Beowulf ducks back behind his cover.

"You . . . you threw a lunch tray at him," says Booth. "And, well—you missed." Embarrassment colors his tone. A brassy wah-wah groans from a muted trumpet in Randy's corner.

"You think I practice that every day?" Beowulf grimaces. "Gimme a chance, here." His arm shoots up to retrieve another tray. "As my ma used to say, 'Practice makes fu**ing perfect.'"

"Hmm." That from Booth. "Quite a woman, your mother."

Beowulf frowns and looks intently at the camera. "Thank you," he says. It sounds sincere. He goes on: anyway, it doesn't have to hit him.

Booth asks about that, "Bring us in on the plan," he says.

"I'm workin' a hunch, here," says Beowulf. "He's only got one gun left." It's an automatic, and it's got maybe a hundred rounds. "He's no pro. But it's more than that. He's smiling. I don't believe the reality of his situation has quite set in. You watch. He'll blow his wad."

Again, he uncoils, launching the tray in a flat spin toward the bishop. This time, the tray keeps its momentum, doesn't flip. But it still swings far wide of its target. No matter. Without waiting even to see where it lands, Beowulf springs up for another tray, and again lets it fly.

The tat-tat-tat of automatic fire follows it. Closer. Another, then another, and the priest fires, finally managing to swat it from the air. Shards of splintered fiberglass rain down on the no-man's-land separating the two men.

Another tray, and the priest laughs. Another, and he sprays the air with metal. Over and over, Beowulf hurls trays at the bishop, and the man gleefully fires away as if this is all a game, and he's shooting at clay pidgins.

Another tray, and a dull thud echoes through the cafeteria. The bishop's head snaps backward. He frowns and looks dazed, but shakes it off and brings his pistol back up.

"I'll be damned," says Booth. "Your mother may have been on to something."

Hell yes, grunts Beowulf. He hurls another tray. This time, a series of clicks from the bishop. It's about damned time: he's empty.

Beowulf smiles savagely and springs forward, arms thrown wide to topple a pair of tables in his path. Ten meters from the priest, and the bishop futilely trains his gun on the advancing Beowulf and holds down the trigger.

Five meters, and he throws the thing at Beowulf—it bounces off chrome armor, then skids across the floor.

Two meters and he covers his head with his arms, an instinctive defensive posture. Beowulf jumps into the air. With a sickening crunch, he lands on the priest's left knee, hyperextending it.

Not strictly necessary, but all part of the show.

A bloody bone spur pushes out through the black fabric of the man's trousers. A follow-cam gets a close-up.

Beowulf grabs the priest's shoulder and pulls him around. Blue-clad men emerge from cover, one picking up the discarded gun and training it on the bishop, slamming a new magazine into place (god knows where he got it).

Beowulf picks the priest up and holds him fast, one arm twisted behind his back, his cheek pressed up against the chrome bear's head so that the camera sees both faces, side by side. The priest isn't smiling anymore.

"Right Rev. John St. George Matheson," says Beowulf, "the people of New York City find you guilty of a capital crime. I am authorized to carry out your summary execution."

With a grim look equal parts determination and disgust, Beowulf looses the other man's arm, brings both hands up to grip his head, then gives it a sharp twist.

A sound like a wet branch snapping, and the bishop falls limply to the ground.

Beowulf looks into the follow-cam.

"Forgive me father," a dramatic pause, "but you have sinned."

The words echo through Booth's virtual hall, boosted by time delay, reverb and a synth chorus, sounding like the testosterone-laced pronouncement of a redneck barker at a monster truck rally.

The crowd goes ape-shit, pumping fists in the air and screaming approval.

A small smile touches the corners of Booth's mouth, though no one sees it. It's all about the spectacle.

If you're gonna feed the monster, only red meat will do.