John Joseph Adams is the series editor ofBest American Science Fiction & Fantasy. He is also the bestselling editor of many other anthologies, such asRobot Uprisings, Dead Man's Hand, Brave New Worlds, Wastelands,and The Living Dead.Recent and forthcoming books include Operation Arcana, Press Start to Play, Loosed Upon the World: Climate Fiction, and The Apocalypse Triptych (consisting of The End is Nigh, The End is Now, and The End Has Come). Called "the reigning king of the anthology world" by Barnes & Noble, John is a winner of the Hugo Award (for which he has been nominated nine times) and is a seven-time World Fantasy Award finalist. John is also the editor and publisher of the digital magazinesLightspeed and Nightmare, and is a producer for WIRED'sThe Geek's Guide to the Galaxypodcast. Find him online at johnjosephadams.com and @johnjosephadams.

Hugh Howey is the author of the acclaimed post-apocalyptic novel Wool, which became a sudden success in 2011. Originally self-published as a series of novelettes, the Wool omnibus is frequently the #1 bestselling book on Amazon.com and is a New York Times and USA TODAYbestseller. The book was also optioned for film by Ridley Scott, and is now available in print from major publishers all over the world. Hugh's other books include Shift, Dust,Sand, the Molly Fyde series, The Hurricane, Half Way Home, The Plagiarist, and I, Zombie. Hugh lives in Jupiter, Florida with his wife Amber and his dog Bella. Find him on Twitter @hughhowey.

Famine. Death. War. Pestilence. These are the harbingers of the biblical apocalypse, of the End of the World. In science fiction, the end is triggered by less figurative means: nuclear holocaust, biological warfare/pandemic, ecological disaster, or cosmological cataclysm.

But before any catastrophe, there are people who see it coming. During, there are heroes who fight against it. And after, there are the survivors who persevere and try to rebuild. THE APOCALYPSE TRIPTYCH will tell their stories.

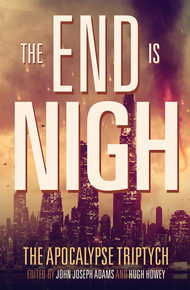

Edited by acclaimed anthologist John Joseph Adams and bestselling author Hugh Howey, THE APOCALYPSE TRIPTYCH is a series of three anthologies of apocalyptic fiction. THE END IS NIGH focuses on life before the apocalypse. THE END IS NOW turns its attention to life during the apocalypse. And THE END HAS COME focuses on life after the apocalypse.

Volume one of The Apocalypse Triptych, THE END IS NIGH, features all-new, never-before-published works by Hugh Howey, Paolo Bacigalupi, Jamie Ford, Seanan McGuire, Tananarive Due, Jonathan Maberry, Scott Sigler, Robin Wasserman, Nancy Kress, Charlie Jane Anders, Ken Liu, and many others.

Post-apocalyptic fiction is about worlds that have already burned. Apocalyptic fiction is about worlds that are burning. THE END IS NIGH is about the match.

Hugh Howey is one of the biggest pioneers in indie publishing, and he has exchanged some great tips with me in helping me build my operation at WordFire. He is brilliant, insightful, and imaginative…and I suppose he can imagine how things might go wrong. He worked with John Joseph Adams to compile three anthologies about the end of the world (because one anthology just isn't enough). John is a prolific anthologist (he's used many of my stories over the years), and also a friend of StoryBundle, in that he often offers free issues of his Lightspeed magazine as bonuses. – Kevin J. Anderson

"Superbly written … the most ambitious, audacious undertaking of its kind."

– NPR, on The Apocalypse Triptych"Adams and Howey are a two-man tour-de-force of post-apocalyptic lit. ... Ultimately, the best thing about The End Is Nigh is how elegantly it balances on the thin line between beauty and devastation. There's no story in the book that didn't break my heart at least a little, and there's none of the twenty-two that hasn't stuck with me, hard."

– Wired, on The End is Nigh"Destined to be a favorite among end-of-the-world enthusiasts."

– FEARnetJohn Joseph Adams

"It was a pleasure to burn. It was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed. With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venomous kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning to bring down the tatters and charcoal ruins of history."

—Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

I met Hugh Howey at the World Science Fiction Convention in 2012. He was a fan of my post-apocalyptic anthologyWastelands, and I was a fan of his post-apocalyptic novelWool. Around that time, I was toying with the notion of editing collaborative anthologies to help my books reach new audiences. So given our shared love of all things apocalyptic—and how well we hit it off in person—I suggested that Hugh and I co-edit an anthology of post-apocalyptic fiction. Obviously, since his name is on the cover beside mine, Hugh said yes.

As I began researching titles for the book, I came across the phrase "The End is Nigh"—that ubiquitous, ominous proclamation shouted by sandwich-board-wearing doomsday prophets. At first, I discarded it; after all, you can't very well call an anthology of post-apocalyptic fictionThe End is Nigh—in post-apocalyptic fiction the end isn'tnigh, it'salready happened!

But what about an anthology that explored lifebefore the apocalypse? Plenty of anthologies deal with the apocalypse in some form or another, but I couldn't think of a single one that focused on the events leading up to the world's destruction. And what could be more full of drama and excitement than stories where the characters can actually see the end of the world coming?

At this point I felt like I was really onto something. But while I love apocalyptic fiction in general, my real love has always been post-apocalypse fiction in particular, so I was loathe to give up on my idea of doing an anthology specifically focused on that.

That's when it hit me.

What if, instead of just editing asingleanthology, we published aseriesof anthologies, each exploring a different facet of the apocalypse?

And so The Apocalypse Triptych was born. Volume one,The End is Nigh, contains stories that take placejustbeforethe apocalypse. Volume two,The End is Now, will focus on stories that take placeduringthe apocalypse. And volume three,The End Has Come, will feature stories that explore lifeafterthe apocalypse.

But we were not content to merely assemble a triptych of anthologies; we also wantedstory triptychsas well. So when we recruited authors for this project, we encouraged them to consider writing not just one story for us, butone story for each volume, and connecting them so that the reader gets a series of mini-triptychswithinThe Apocalypse Triptych. Not everyone could commit to writing stories for all three volumes, but the vast majority of our authors did, so most of the stories that appear in this volume will also have sequels or companion stories in volumes two and three. Each story will stand on its own merits, but if you read all three volumes, the idea is that your reading experience will be greater than the sum of its parts.

In traditional publishing, this kind of wild idea—publishing not just a single anthology, but atrioof anthologies with interconnected stories—would be all but impossible, so it was just as well that Hugh and I had already decided to self-publish. But the notion that this was something that traditional publishing wouldn't—or couldn't—do made the experiment even more compelling, and made working on this project even more exciting.

Post-apocalyptic fiction is about worlds that have already burned. Apocalyptic fiction is about worlds that are burning.

The End is Nighis about the match.

Robin Wasserman

Here's how it works in my business: First, you pick a date—your show-offs will go for something flashy, October 31 or New Year's Eve, but you ask me, pin the tail on the calendar works just as well and a random Tuesday in August carries that extra whiff of authenticity. Then you drum up some visions of hellfire, a smorgasbord of catastrophe—earthquake, skull-faced horsemen sowing flame and famine in their wake, enough death and destruction to make your average believer cream his pants—and that's when you toss out the life-preserver, the get-out-of-apocalypse-free card. Do not passgo, do not collect $200, do not get consumed by the lake of righteous fire, go directly to heaven on a wing and a prayer and a small contribution to the cause, specifically the totality of your belongings and life savings, 401Ks and IRAs—for obvious reasons—included.

Here's how it's supposed to work in my business: You tuck that money away for safe keeping, preferably in a bank headquartered in a non-extradition country, await the end days with clasped hands and kumbayas, and then, when the sun rises on an impossible morning, oh, you praise the Lord for hearing your prayers and offering a last minute reprieve, you go ahead and praise yourself for out-arguing Abraham and saving your modern day Sodom and Gomorrah, and let's all give thanks for living to pray another day, even if we live in bankruptcy court.

If you don't have the juice to pull that one off, there's always the mulligan—oopsy daisy, misread the signs, ignored the morning star, overlooked the rotational angle of Saturn, forgot to carry the one, my bad. Dicey, but better than drinking the Kool-Aid—and if you can't envision a Great Beyond worse than prison, you might be in the wrong line of work. You do your job right, by the time the fog clears and the pitchforks and torches hit your doorstep, you're long gone, burning your way through those lifetimes of pinched pennies one piña colada at a time.

Like I said: Supposed to.

I'm a man who likes a back-up plan, a worst-case-scenario fix for every contingency, a bug-out route in case anything goes wrong. Never occurred to me to plan for being right.

The signsare bullshit. Have to be. You know who "read" the signs? Pick your poison: Nostradamus. Jesus Christ. Jim Jones, Martin Luther, the whole Mayan civilization. Every flim-flam man from Cotton Mather to Uncle Sam. And every single one of them screwed the pooch. Then, somehow, along comes me. You know what they say about those million monkeys banging away on their million typewriters until one of them slams out Hamlet?

Just call me Will.

• • • •

Hilary dumped the kid five days after I made the prophecy, nine months before the end of the world. I remember, because by that point the Children had rigged up the calendar, a blinking LCD screen hanging over the altar to keep them constantly apprised of the time they had left. Nine months had seemed an auspicious period—long enough for the kind of slow burn panic that empties wallets but stops short of bullets to the brain, brief enough that I could keep smiling and stroking the Children of Abraham without letting slip that I wanted to throttle every insipidly trusting last one of them. But Hilary tracking me down had me questioning the timeframe, and not just because she dumped her stringy ten-year-old in my lap and took off for greener and presumably coke-ier, pastures.

I'd only been Abraham Walsh, né none of your concern, for the last five years, and before that Abraham Cleaver, and beforethat, back in the days when Hilary had decided to fuck with her parents by fucking the itinerant faith healer, Abraham Brady. If a headcase like her had managed to track me through three names, ten years, and twelve states, who knew how many cops, parishioners, shotgun-toting fathers or snot-dripping toddlers might have picked up the trail?

I had a good thing going in Pittstown, had for the last three years. The Children of Abraham had picked up about forty families and, thanks in large part to the penitent auto-parts mogul Clark Jeffries, had cobbled together some nice digs: a church, a few houses, a gated estate complete with indoor pool. Unfortunately, Clark Jeffries' efforts to buy himself into heaven—not to mention his attempt to paper over two decades of embezzlement and hookers—didn't extend to forking over the land deeds or any appreciable fraction of his ill-gotten gains. Always a borrower and a lender be, that was Clark's way. Donations were for suckers.

We weren't a growth operation—proselytizing only gets you the wrong kind of attention—and so we didn't go in for fancy costumes or banging cymbals in airports. Tacky. None of that polygamy stuff either, not if you wanted to keep under the radar, and definitely not if experience had taught you that one wife was already one too many. The Children were a pacific and obedient bunch, and even if it got exhausting at times, playing God's sucker so I could sucker them, the sheets were thousand thread count and there was a hot tub behind the indoor pool. Better than working for a living, especially eight months and twenty-six days from retirement. Then in walks Hilary Whatshername and the apparent fruit of my loom, Judgment Day come early.

"And what do I know about kids?" I said.

"But you've got so many Children, Father Abraham." It was her best look: wide-eyed innocent with a soupçon of irony. It was the reason I'd kept her around for all those months in the first place, even though she'd seen through the big tent act from the start and could have set her daddy and his country club buddies at me on a whim. At twenty-five, she'd nearly managed to pass as a teenager; a decade later, she'd have had trouble persuading a mark she was under forty. But even with sun-spots, a muffin-top, and the ghost of a moustache, there was still a certain sex appeal there—like a stripper who's hung up her thong but still knows how to shimmy, exuding an air of possibility, a slim hope that at any moment, the clothes might come off. "What's one more?" she asked.

"Come the fuck on."

"You'll get the hang of it," she said. "Probably."

"He's yourkid," I tried. "You want to bet on probably?"

"Better you than my parents. Better anyone than me."

The kid didn't say anything. We were sequestered in my office, where Hilary had settled herself onto the leather couch and kicked her feet up on the Danish modern like she owned the place. A cigarette dangled from her lips that would, knowing Hil, soon be stubbed out on the teak, leaving behind a small but permanent scar, her very own Hilary was here. Which I wouldn't have begrudged her if she hadn't been leaving so much else behind.

The kid, on the other hand, was still standing at attention, hands clasped before him, church-style, his glance not bothering to stray toward any of the room's curiosities, the titanium safe or the shrine with its portrait of me (a substantially less flab-faced and balding me) in the thick gold frame. Just beyond the door, in the veloured ante-room, my Children waited, no doubt, with ears pressed to the wall, ostensibly to ensure that this wasn't some kind of clever assassination attempt, likely hoping it was more of a holy visitation, Mary and overgrown Baby Jesus come to make their pre-apocalyptic crèche complete. Meanwhile here was this kid, center of the action, eyes glazed over like he was watching two strangers play a particularly dull game of cribbage. No indication that he realized he was the pot. Here's his mother dumping him on a gray-hair with the body of a linebacker—a hundred push-ups every morning since I sprouted my first pubic hair, with plans to keep it up until the day my dick gives out, thank you very much—who happens to be,surprise, you probably thought he was dead, but!his long-lost daddy, and the kid's about as fired up as a pet rock.

I envied him his decade of ignorance. There's nothing more beautiful than a void, a blank screen you can project all those Technicolored fantasies onto, no one to tell you they're misplaced or far-fetched. Easy enough to fill that father-shaped hole with the tall tale of an astronaut daddy stranded on the moon or a CIA daddy defusing bombs in some windswept foreign desert. That could be an epic hero's blood running through your veins, the strength of an Achilles, the bravery of an Odysseus encoded in your DNA. Who wouldn't be disappointed to come face to face with the real thing, to trade in epic poetry for the genetic equivalent of a joke on a bubble gum wrapper? I knew he couldn't look at me without seeing himself, at least the funhouse mirror version—congratulations, this will soon be your life—just like I couldn't look at him without wincing at what had once been and what was to come.

His hairline was several inches closer to the brow line than mine but already receding, and it would be a few more decades before his crooked nose and uneven eyes came into their Picasso-like own, but he was already skidding down a slippery slope. I'd had that same thatch of sandy hair, and whatever I'd lost on top was replenishing itself in my nostrils and ears, conservation in action. I'd have to be blind to doubt he was my kid, and he'd have to be nuts not to want to trade me in for a better model. But he didn't look disappointed. He didn't look much of anything. I wondered if he was autistic or something. Glory be. Not only did I have a kid, but the kid was weird.

"Parenting's not complicated," Hilary said. "Accept that you'll fuck him up, whatever you do. Just try not to fuck up so bad that it kills him."

"I'll put him out on the street as soon as you're gone," I warned her.

She grinned, the way only someone who's seen you roll off her naked body with a groan and amust've had too much to drinkwhile she saidit happens to the best of 'em and you both thoughtno, it damn well doesn'tcan grin.

"No. You won't," she said. And she was right about that, too.