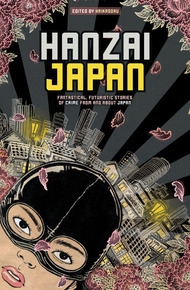

Edited by Haikasoru: Nick Mamatas and Masumi Washington

Nick Mamatas is an editor for Haikasoru, an imprint dedicated to Japanese science fiction, fantasy, and horror in translation. Masumi Washington is Haikasoru's editor-in-chief.

A murderer doing time in Hell. A girl who just wants to win her high school band contest...no matter what it takes. Sumo wrestlers with a supernatural secret. A future Tokyo where vampires are menial laborers nursing long-held grudges against humanity. And even a very conscientious, if unstable, Universal Transverse Mercator projection. These crime and mystery stories from and about Japan explore myth, technology, the sharpness of a sleuth's mind, and the darkness in the hearts of criminals. Read these stories and learn that hanzai means crime!

"It's this spirited, loving, bloody rebellion against the genre rulebook that makes these stories tick, that brings them together. Winding through points of view from an ex-pat young woman exploring the quiet deaths of a broken-down theme park, to two American fuckboys getting wasted and in serious trouble in New York's Little Tokyo, to a group of Yakuza bank robbers watching a PowerPoint on how best to utilise Godzilla in their latest heist, Hanzai Japan shows both Japan and the West through broken lenses, a playful perversion of how we see ourselves and the other."

– Katy Lees, reviewer for Dirge Magazine"All the stories are solid and build their own world, and the range of voices gives you everything from atmospheric horror to the creepily fantastic to stories dripping with dark humor and a wink at the readers. Hanzai Japan is definitely different from a lot of what is on the market and it's a fun ride all the way through."

– Danica Davidson, author of Minecraft novel: Escape from the Overworld and writer for Otaku USA Magazine"All of which is to say that Haikasoru has put out another winner of an anthology, joining The Future is Japanese (2012) and Phantasm Japan (2014) in presenting a diverse array of voices, both Western stars (Valentine, Evenson) and Japanese authors in translation, to show just how appealing and intertwined the fiction coming out of Japan can be for the Western genre audience."

– Karen Burnham, contributor to Locus Magazine"So if this doesn't sound like a trippy, fun, and highly entertaining collection to you, then I'm not 100% sure that you're human. I mean, maybe you're a space lizard in a human suit. With terrible taste. If my review of Hanzai Japan did pique your interest, though, then go grab a copy."

– Rachel Cordasco, writer for SF SignalFrom "Hanami," a Lydia Chin/Bill Smith short story by S. J. Rozan

Every time I come to Washington it rains.

I don't know why this should be, but my father used to tell my brothers and me that there's no point in denying reality, even reality that's ridiculous. Rain fell insistently, tracing diagonal lines across the windows, as the Acela train Bill Smith and I were riding pulled into Union Station.

"It's still beautiful," Bill said. "Soggy, but at least down here it's spring."

"You don't have to try to make me feel better. I don't believe I have some paranormal effect on the weather and it rains because I'm coming. I just think I unconsciously but cleverly time my trips here to make sure to coincide with the rain."

"Not a paranormal effect on the weather, just a preternatural relationship with it? Sure, why not?"

We swung our overnight bags down and beat it to the subway. In Washington they call it the Metro and it runs on rubber wheels, and in the place we came out, Dupont Circle, it had a huge sci-fi escalator to the street. "You think we'll be on Mars when we get to the top?" I asked as the gray sky in the round opening came closer.

"I think we're already on Mars if we've really taken this case."

"We can't not take it. I told you, Moriko's one of my oldest friends. We were super close in high school until her family moved here her senior year. I used to date her big brother. Maybe you can't take it. But I have to."

"I can't take what, the fact that you used to date her older brother? Oh, you mean the case. What kind of person would leave his partner on her own with a client who thinks she's a fox? Besides, from what you say she actually is a fox, though not the kind she thinks she is."

"Hands off. That's the whole problem here—a man after her who she doesn't want."

"What makes you think she wouldn't want me?"

"Let me count the ways."

I lofted my umbrella, Bill sunk his head in his raincoat collar, and we splashed the two blocks to the row house where Moriko Ikeda lived in an apartment on the parlor floor.

As I told Bill, Moriko and I have been close since high school. We went to Townsend Harris in Flushing, Queens, which is stuffed full of brainy Asian kids but, as my brother Tim never lets me forget, isn't Stuyvesant. My four brothers and I all went to high schools you had to test into, but different ones. Tim was already at Stuyvesant when my tests came up; I didn't even fill out the application. Why? The different-schools thing hadn't applied to elementary school. I was the youngest—and a girl—and I followed my brothers all the way through Sun Yat-Sen in Chinatown. I couldn't wait to get to a school where, when anyone asked if I was related to such-and-such a kid named "Chin," I could say I wasn't, not just wish I wasn't.

Moriko and I hit it off from the beginning, even though the Chinese and Japanese kids mostly eyed each other with suspicion (and the Koreans eyed both of us that way, and the black kids eyed the Latino kids that way, and the white kids were too stunned by finding themselves in the minority to do anything but huddle together for warmth). With me and Moriko, maybe it was an opposites-attracting kind of thing. I was a short, straightforward, practical jock; she was tall, elegant, sweet, and spacey.

Never this spacey, though. She'd called yesterday to ask me to come to Washington as a last-ditch attempt to solve her problem, which was: a man had stolen her kitsunebi, and since she'd die without it, she had to do what he wanted so he'd give it back. Kitsunebi is the soul of a kitsune, a fox spirit, and in this case what the man wanted was for Moriko to marry him.

Moriko buzzed us in within seconds of my pressing her doorbell. We'd stepped into the building's small entry hall and I was folding my umbrella for stashing when she opened the glass-paneled inner door. Her eyes lit up when she saw me, and I'm sure mine did when I saw her. Bill's eyes I didn't look at because I didn't want to know.

You have to understand: Moriko is gorgeous. She's not actually super tall, maybe five-ten, but she's so slender that she gives a long-limbed, languid impression. She seems not to walk so much as flow, and the shoulder-length hair framing her narrow, high-cheekboned face is as black and glossy as her skin is pale.

Paler than usual, today. She led us into her apartment through a pair of large double doors, closed them behind her, and hugged me. "Thank you for coming, both of you. Though I'm feeling guilty about calling you. I don't know what you can possibly do. Oh, I'm sorry, that's so rude of me." She extended her hand to Bill. "Moriko Ikeda."

"Bill Smith. Don't be sorry and don't feel guilty. I haven't been to Washington in awhile. Happy to come down."

"I wish I could have provided better weather."

"Don't worry about it, that's Lydia's fault."

Moriko raised her delicate eyebrows but I didn't explain. After a moment she said, "I have tea. I'll bring it right in."

While Moriko went to get the tea, Bill whispered to me, "Do kitsune control the weather?"

"No. That was human small talk."

I'm always surprised when I find myself explaining something to Bill. As he's pointed out more than once, I'm the Asian person in our relationship. But he, rumpled, antisocial, and blue-collar as he appears—though not today; today he wore a sharp navy suit with a white shirt and blue-and-silver tie—is the one with the deep background in art, music, and all kinds of culture, including Asian culture. So long before Moriko hired us, he'd heard of kitsune; but apparently he wasn't familiar with their fine points.

I was, because I'd looked them up.

For example, they're usually called "fox spirits," but that makes them sound like ghosts and they're not ghosts. They're regular foxes who've reached a great age and attained wisdom and magical powers. Like shapeshifting. Into old men, young girls, and beautiful women.

For another example, they carry their souls, their kitsunebi, outside their bodies in glowing globes of fire. In fox form, they hold the globes on their tails. When they're humans, where to keep the globes—the kitsunebi-dama—becomes problematic. And it seemed that Blake Adderly, up-and-coming young hotshot D.C. power broker, had, in the course of dating Moriko, discovered and walked off with hers.