Robert J. Sawyer is one of only eight writers ever to win all three of the world's top awards for best science-fiction novel of the year: the Hugo (which he won in 2003 for Hominids), the Nebula (which he won in 1996 for The Terminal Experiment), and the John W. Campbell Memorial Award (which he won in 2006 for Mindscan). He has also won the Robert A. Heinlein Award, the Edward E. Smith Memorial Award, and the Hal Clement Memorial Award; the top SF awards in China, Japan, France, and Spain; and a record-setting sixteen Canadian Science Fiction and Fantasy Awards ("Auroras").

Rob's novel FlashForward was the basis for the ABC TV series of the same name, and he was a scriptwriter for that program. He also scripted the two-part finale for the popular web series Star Trek Continues. His 24th novel, The Oppenheimer Alternative, was published in June 2020.

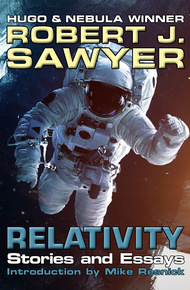

This Aurora Award-winning collection from Hugo and Nebula Award-winning author Robert J. Sawyer gathers eight short stories, four speeches, eleven articles, and all twelve of his "On Writing" columns from On Spec magazine. Featuring a foreword by Mike Resnick and introductory notes on most pieces by Sawyer. Originally published in hardcover in 2004 by ISFiC Press.

Excerpt from the Aurora Award and Arthur Ellis Award-winning short story "Just Like Old Times":

The transference went smoothly, like a scalpel slicing into skin.

Cohen was simultaneously excited and disappointed. He was thrilled to be here—perhaps the judge was right, perhaps this was indeed where he really belonged. But the gleaming edge was taken off that thrill because it wasn't accompanied by the usual physiological signs of excitement: no sweaty palms, no racing heart, no rapid breathing. Oh, there was a heartbeat, to be sure, thundering in the background, but it wasn't Cohen's.

It was the dinosaur's.

Everything was the dinosaur's: Cohen saw the world now through tyrannosaur eyes.

The colors seemed all wrong. Surely plant leaves must be the same chlorophyll green here in the Mesozoic, but the dinosaur saw them as navy blue. The sky was lavender; the dirt underfoot ash gray.

Old bones had different cones, thought Cohen. Well, he could get used to it. After all, he had no choice. He would finish his life as an observer inside this tyrannosaur's mind. He'd see what the beast saw, hear what it heard, feel what it felt. He wouldn't be able to control its movements, they had said, but he would be able to experience every sensation.

The rex was marching forward.

Cohen hoped blood would still look red.

It wouldn't be the same if it wasn't red.

Excerpt from the speech: The Future is Already Here.

To my way of thinking, the central message of science fiction is this: "Look with a skeptical eye at new technologies." Or, as William Gibson has put it, "the job of the science-fiction writer is to be profoundly ambivalent about changes in technology."

Now, certainly, there are science-fiction writers who use the genre for pure scientific boosterism: science can do no wrong; only the weak quail in the face of new knowledge. Jerry Pournelle, for instance, has rarely, if ever, looked at the downsides of progress. But most of us, I firmly believe, do take the Gibsonian view: we are not techie cheerleaders, we aren't flacks for big business or entrepreneurism, we don't trade in utopias.

Neither, of course, are we Luddites. Michael Crichton writes of the future, too, but he's not really a science-fiction writer; if anything, he's an anti-science-fiction writer.

Indeed, both Gregory Benford and I have discussed with our shared agent, Ralph Vicinanza, why it is that Crichton outsells us. And Ralph explained that he could get deals at least approaching those Crichton gets if—and this was an unacceptable "if" to both me and Greg—we were willing to promulgate the same fundamental message Crichton does, namely, that science always goes wrong.

When Michael Crichton makes robots, as he did in Westworld, they run amuck, and people die. When he clones dinosaurs, as he did in Jurassic Park, they run amuck and people die. When he finds extraterrestrial life, as he did in The Andromeda Strain, people die.

Crichton isn't a prophet; rather, he panders to the fear of technology so rampant in our society—a society, of course, which ironically would not exist without technology. His mantra is clearly the old B-movie one that "there are some things man was not meant to know."

The writers of real SF refuse to sink to fear-mongering, but neither do we overindulge in boosterism—both are equally mindless activities.

Still, we do have an essential societal role, one being fulfilled by no one else.