Robert J. Sawyer is one of only eight writers ever to win all three of the world's top awards for best science-fiction novel of the year: the Hugo (which he won in 2003 for Hominids), the Nebula (which he won in 1996 for The Terminal Experiment), and the John W. Campbell Memorial Award (which he won in 2006 for Mindscan). He has also won the Robert A. Heinlein Award, the Edward E. Smith Memorial Award, and the Hal Clement Memorial Award; the top SF awards in China, Japan, France, and Spain; and a record-setting sixteen Canadian Science Fiction and Fantasy Awards ("Auroras").

Rob's novel FlashForward was the basis for the ABC TV series of the same name, and he was a scriptwriter for that program. He also scripted the two-part finale for the popular web series Star Trek Continues. His 24th novel, The Oppenheimer Alternative, was published in June 2020.

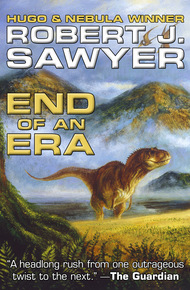

Paleontologist Brandon Thackeray is eager to find out what killed the dinosaurs. With a newly developed, still-experimental timeship, he will be able to do what no human being has ever done: stand face-to-face with a living, breathing dinosaur. But he and his partner (and rival) Miles "Klicks" Jordan discover that they are not the only intelligent creatures on Earth at the end of the Cretaceous. There's a war going on and the dinosaurs are right in the middle of it.

"Audacious — Sawyer has reached far beyond the grasp of the standard SF time-travel story. End of an Era would have to rank as one of the finest Canadian or American science fiction novels I have read in the last 10 years. Definitely a better book than Jurassic Park — faster paced, avoiding the expository dumps that Crichton uses, and supplying us with much more believable characters. Faced with a staggering amount of possible loose threads, Sawyer manages to tie things into one of the tightest knots possible."

– The Edmonton Journal"Audacious, informed, and compelling — displays the author's breadth of imagination and humanity. It's not too much to say that this is one of the most accomplished SF novels of the last 10 years."

– Quill & Quire"In the past decade, Robert Sawyer has become one of the most popular writers of science fiction. Many of his fans, though, haven't read some of his early work. Now's the time, as the author has revised End of an Era, a novel that shows the originality and talent obvious in more recent titles like Calculating God and FlashForward. This isn't the first science fiction novel to take readers back to the time of the dinosaurs, but with Sawyer, you expect something unique. And you won't be disappointed."

– The Denver Rocky Mountain NewsWe were hanging by a thread.

Okay, it was really a steel cable, about three centimeters thick, but it didn't give me any more reassurance.

And I wished that damned swaying would stop.

Our time machine had been lifted up by a turbo Sikorsky Sky Crane, and was now hanging a thousand meters above the stark beauty of the Badlands of Alberta. The pounding of the helicopter's engines thundered in my ears.

I wished that noise would stop, too.

But most of all, I wished Klicks would stop.

Stop being an asshole, that is.

He wasn't really doing anything. Just lying there in his crash-couch, on the other side of the semicircular chamber. But he's so smug, so goddamned smug. The couch is like a high-tech La-Z-Boy upholstered in black vinyl and mounted on a swivel base. Your feet are lifted up, your spine tips at an angle, and a tubular headrest supports your noggin. Well, Klicks had his legs crossed at the ankle, and his arms interlaced behind his head. He looked so bloody calm. I knew he was doing it just to bug me.

I, on the other hand, was gripping the armrests of my crash-couch like one of those poor souls who are afraid to fly.

It was about two minutes until the Throwback.

It should work.

But it might not.

In two minutes we could be dead.

And he had his legs crossed.

"Klicks," I said.

He looked over at me. We were almost exactly the same age, but opposites in a lot of ways. Not that it matters, but I'm white and he's black — he was born in Jamaica and came to Canada as a boy with his parents. (I always marveled that anyone would leave that climate for this one.) He's clean-shaven and hasn't started to gray yet. I've got a full beard, have lost about half my hair, and what's left is about evenly split between gray and brown. He's taller and broader-shouldered than me, plus, despite having a job that involves as much time at a desk as mine does, he's somehow avoided middle-age spread.

But most of all, we're opposites in temperament. He's so cool, so laid-back, that even when he's standing he gives the impression of being stretched out somewhere, tropical drink in hand.

Me, I think I'm getting ulcers.

Anyway, he looked in my direction, his face a question. "Yeah?"

I didn't know what I had intended to say. After a moment, I blurted out, "You really should put on your shoulder straps."

"What for?" he replied in that too-smooth voice of his. "If the programmed stasis delay works, it won't matter if I'm standing on my head when they rev up the Huang Effect. And if it doesn't work . . ." He shrugged. "Well, man, those straps will slice you like a hard-boiled egg."

Typical. I sighed and pulled my straps tighter, the thick nylon bands reassuringly solid. I saw him smile, just a bit — but also just enough so that he could be sure that I would see the smile, the patronizing expression.

A crackle of static from the radio speaker fought to be heard above the sounds of the helicopter, then: "Brandy, Miles, are you ready?" It was the precise voice of Ching-Mei Huang herself, measured, monotonal, clicking over the consonants like a series of computer relays.

"Ready and waiting," Klicks said, jaunty.

"Let's get it over with," I said.

"Brandy, are you okay?" asked Ching-Mei.

"I'm fine," I lied, wishing I had a bucket to throw up into. The swaying back and forth was getting to me. "Just do it, will you?"

"As you say," she replied. "Sixty seconds to Throwback. Good luck — and God protect." I was sure that little reference to God was for the sake of the network cameras. Ching-Mei was an atheist. She only had faith in empirical data, in experimental results.

I took a deep breath and looked around the small room. His Majesty's Canadian Timeship Charles Hazelius Sternberg. Great name, eh? We'd had a list of about a dozen paleontologists we could have honored, but old Charlie won out because, in addition to his pioneering fossil hunting in Alberta, he'd actually written a science-fiction story about time travel, published in 1917. The PR people loved that.

Ching-Mei's voice over the radio speakers: "Fifty-five. Fifty-four. Fifty-three."

Anyway, nobody ever calls it His Majesty's Canadian Etc. Instead, our timeship is almost universally known as the Sternberger, because to most people it looks like a fat hamburger. To me, though, it looks more like a squat version of the Jupiter 2, the spaceship from that ridiculous TV series Lost in Space. Just like the Space Family Robinson's vehicle, the Sternberger was essentially a two-level disk. We even had a little dome on the roof like they did. Ours housed meteorological and astronomical instruments; there was room enough for one person to squeeze into it.

"Forty-eight. Forty-seven. Forty-six."

The Sternberger was much smaller than the Jupiter 2, though — only five meters in diameter. Our lower deck wasn't designed for people; it was just 150 centimeters thick and consisted mostly of our water tank and part of the garage for our Jeep.

"Forty-one. Forty. Thirty-nine."

Our upper deck was divided into two halves, each semicircular in shape. One half contained the habitat. Along its curving outer wall was a kidney-shaped worktable, our radio console, and a compact laboratory unit crammed with geological and biological instruments. The straight back wall, marking the ship's diameter line, had three doors built into it. Door number one — does anybody remember Monty Hall? — led to a little ladder that angled up into the rooftop instrumentation dome and to a ramp that went down the meter and a half to the outer entrance door. Door number two led to the Jeep's garage, which took up the height of both decks. Door number three gave access to the washroom stall.

"Thirty-four. Thirty-three. Thirty-two."

Mounted against the central wall in the gaps between the doorways were a small stand with an old microwave oven on it, a large food refrigerator, a bank of three equipment lockers swiped from some high school demolition sale, and a small medical refrigerator with a first-aid kit on top. Bolted to the floor were the swivel bases for our two crash-couches.

A time machine.

An actual time machine.

I just wish I knew exactly where it was going to take me.