Ian Bogost is Ivan Allen College Distinguished Chair in Media Studies and professor of interactive computing at the Georgia Institute of Technology. He is the author of many books, including How to Do Things with Videogames and Alien Phenomenology, or What It's Like to Be a Thing (both Minnesota), as well as Unit Operations: An Approach to Videogame Criticism and Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. He is the award-winning game designer of A Slow Year, Cow Clicker, and more.

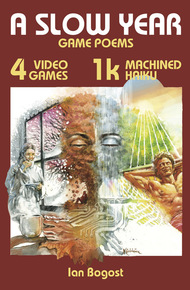

A Slow Year is a collection of four one kilobyte game poems - originally created for the Atari Video Computer System - one for each season, about the experience of observing things. Neither action nor strategy, each game requires a different kind of sedate observation and methodical input.

This digital version of A Slow Year comes with PC and Mac-compatible game installers and an accompanying eBook, which includes essays about the commonalities between videogames and poetry, as well as 1,024 machined haiku—poetry generated by computer—8 bits worth for each season.

A collection of four one kilobyte games (on PC and Mac, and originally made for the Atari Video Computer System), one for each season, about the experience of observing things. Includes a book with essays about the commonalities between videogames and poetry and 1,024 machine-created haiku.

"This is a kind of game that could have been created thirty years ago, but wasn’t. By choosing the Atari, Bogost reflects on a shared nostalgia and in- vites the player to think about issues of time and experience. It points to different paths videogames could have taken and the undiscovered ones out there still waiting. Technology is not the limit; A Slow Year proves it never was."

–Rod Humble, CEO, Linden Lab"A Slow Year resurrects an abandoned platform and excavates from it a series of sad and lovely meditations on perception and time. Bogost demonstrates the power that can be summoned by turning away from our obsession with games’ technological future and attending, for a moment, to the particular formal qualities of their technological past. This game is an important mile- stone in the development of videogames as an expressive form."

–Frank Lantz, Director, NYU Game Center and designer of Drop7"True to the limitations of the Atari system, which had no built-in data for displaying text but relied instead on custom images, there is no text within the game and very little interface. To change between the four games on the Atari, players press a switch. In emulation, players can swap by pressing Tab. In our age of endless menus and update dialogs, it’s nice to be presented with nothing but the pure game."

–Tommy Rouse, review at Pitchfork"To me, the two projects create meaningful contrast. Maybe the Cow Clicker players, the media, the meme-hungry internet and even some of Bogost's own colleagues think that game is his greatest achievement. But Frank Lantz believes Cow Clicker and A Slow Year stand side by side as Bogost's best work ever, transcending classic models of expression and rhetoric."

–Leigh Alexander, Kotaku - “The Life-Changing $20 Rightward-Facing Cow”Perhaps games and poetry share a common, if underdeveloped lineage. Good games, like good poems, are provocation machines. Despite the implications of fixity and visual perception the name Imagism suggests, the stuff of provocation in poems and in games are the same: the behavior of artifacts.

When you play Jonathan Blow’s game Braid, a puzzle platformer that weaves mechanics of time manipulation with themes of regret, you enter into a relationship with its creator not by virtue of the story being told to you through fragments, nor by the puzzles that comprise its levels. Rather, allegorical themes emerge from interactions with the game’s temporal dynamics, each of which answers the question, "what if I could do it over again?" Pound’s poem and Blow’s game are clearly driven by specific, personal experiences. But what those experiences "really are" matters less than the evocative residue they leave.

Just like Pound’s moment on the Paris metro platform, Blow’s meditation on contrition is particular enough to become productively evocative. When I play the game, it offers me a set of distortions with which to consider my own regrets symbolically: what if I could do that one thing again but hold this other thing constant? What if I could erect a vortex that slows you down while I race to catch up? This isn’t a process of getting out of the player’s way to facilitate his creativity, as in games like Little Big Planet or Spore, which seek primarily to facilitate player inventiveness. No, in Pound’s and Blow’s cases, the author remains, lurking from all around like a shade.

In games like Blow’s and poetry like Pound’s, the player encounters the machine its creator fashioned, and that designed configuration inspires him to consider what it means that its gears mesh. It is not authorship that creates this experience, but the residue of configuration. When I manipulate a system, I ask myself what its operation invites me to conclude about myself and my world. Yet, this is not a free-for-all either, in which poem or game can mean whatever I choose. I subject myself to a situation set up by a creator, who promises evocativeness of a particular kind. Then I struggle to come to grips with the machinery I operate.

Imagist poetry shows us how an abundance of meaning can emerge from a very small number of tightly crafted, specific components, rather than from enormous expanses of possibility. Pound’s poem leaves enough room to see the Metro riders as the doleful subjects of labor, or as glistening Venuses amidst the iron. The reader does not receive the message of the poem, but excavates its images and uses those to craft relevance.

Excavation. The relationship of player to game is like that of the archaeologist to the ruin. A game is a remnant of something fashioned and disposed by its creator. When we play, we excavate. We find rusted yokes, shards of vessels, inscriptions of rites. We find systems that symbolize. We find evidence of utterly lost civilizations that we can never fully understand. They exist to summon wonder instead of clarity.

This is an intimate relationship, too. Once, someone used that implement. That strategem put a piece of a puzzle within reach. There, someone prayed some alien prayer. Overcoats clutched passengers. Rain doused lawn equipment. Men fantasized about mistakes undone.

The author of a videogame has by no means resigned. Yet, he has also not sent a message to be received. Players unearth the operation of thought, of knowledge, of ritual, of behavior from the fragments of systems left behind. We fiddle so that we might understand ourselves by means of another’s implements.