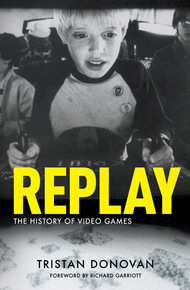

Tristan Donovan is a journalist and the author of Replay: The History of Video Games and Fizz: How Soda Shook Up the World. His writing has appeared in publications such as The Times, Stuff, Eurogamer, Community Care, Gamasutra and many more. He lives in Lewes, East Sussex, UK.

A riveting account of the strange birth and remarkable evolution of the most important development in entertainment since television, Replay: The History of Video Games is the ultimate history of video games. Based on extensive research and more than 140 exclusive interviews with key movers and shakers from gaming’s past and present, Replay tells the sensational story of how the creative vision of game designers gave rise to one of the world’s most popular and dynamic art forms. Features a foreword by Richard Garriott, aka Lord British.

Replay is the ultimate history of video games. Based on extensive research and over 140 exclusive interviews with key movers and shakers from gaming's past, Replay tells the sensational story of how the creative vision of game designers gave rise to one of the world's most popular and dynamic art forms.

"An amazing work. Comprehensive and wide ranging – yet engrossing and splendidly entertaining. If you read only one history of video games – Replay is it."

–Eugene Jarvis, creator of Defender, Narc and Smash TV"I can’t think of a reason that you shouldn’t go and order a copy of it immediately…If you enjoy reading about games, there’s absolutely no way that you’re not going to find spending quality time with this rewarding."

–Kieron Gillen, Rock Paper Shotgun"Striking a near-perfect balance between art and commerce, Replay is the most comprehensive history of videogames so far."

–Edge"Whether you grew up with your eyes glued to Adventure or Super Mario Bros., with your hand around a joystick or inside a Nintendo Power Glove, this is one history lesson worth its weight in quarters."

–Rob Lott, BookgasmThe Sinclair ZX80 home computer was creation of British inventor Clive Sinclair. Affectionately nicknamed “Uncle Clive” by his fans, Sinclair was the living embodiment of a British boffin with his thin spectacles, balding scalp and ginger beard.

He built his reputation during the 1960s and 1970s by making super-cheap versions of the latest cutting-edge consumer electronics, from cut-price hi-fis and portable TVs to digital wristwatches and pocket calculators. The low price was sometimes reflected in unreliability, most notably the digital Black Watch that didn’t work and almost bankrupted his company due to the volume of returns, but items such as his pocket calculators brought expensive electronics to the mass market.

In keeping with Sinclair’s belief in low-cost electronics, the ZX80 cost just £99.95 fully assembled, or £79.95 if bought as a kit to assemble at home with a soldering iron, but it offered features comparable to rival systems costing hundreds of pounds more. It quickly became the U.K.’s biggest- selling home computer. The success of the ZX80 marked the moment when affordable home computing became a reality in Britain.

The ZX80 was the machine that the U.K.’s legions of would-be computer enthusiasts had been waiting for. “Machines like the Commodore PET and Apple II were a bit too far out of reach for the average interested school kid to buy,” said Jeff Minter, a Basingstoke teenager who had fed his interest in home computers by making games on his school’s Commodore PET until the ZX80 arrived. “Uncle Clive gave us affordable computing for the first time in the shape of the ZX80.”

By the time Sinclair released the cheaper, more powerful and even more successful ZX81 in March 1981, many of those who bought the ZX80 had reached the same conclusion: They should make and sell games. And since few shops sold games, they copied their games onto blank cassette tapes and sold them via mail order.

One of the first people to make an impact with a mail order game was Kevin Toms, a programmer from the seaside town of Bournemouth, who in 1981 released Football Manager on the ZX81. The game evolved out of a board game Tom had designed about running a soccer club that was part inspired by Soccerama, a 1968 board game about football management. After getting a ZX81, Toms realised his board game would be make a better computer game: “It gave me a much better tool to run the game on, especially for automating things like league table calculations and fixtures. It also helped me to make the simulation of what was happening more realistic and interesting.”

Football Manager was text-only, but it captured the drama of football in a way that the era’s basic action-based soccer games could not, swinging from the highs of steering your club to the top of the league to the lows of seeing your star player injured in a match. And just as was the case for everyone else, selling the game via mail order was really the only option open to Toms. “When I started there were no retailers at all,” said Toms. “The best way to sell a game was by mail order direct to the public. So that is what I did.” Toms’ three editions of Football Manager would go on to sell close to 2 million copies across a number of computer formats and create a video game genre that is still a top seller today.

The ZX80 also attracted the curiosity of Mel Croucher, a former architect from Portsmouth. “When Uncle Clive came up with the ZX80, I already had an entertainment cassette business,” said Croucher. “An advert appeared for some computer software on a cassette and I think that cassette cost four or five quid. I had already produced audiocassettes for about 30p a throw including the labels and packaging, so I thought I’d give games a go and switched to computer software that day. The reason was a mixture of avarice and ignorance.”

Croucher’s debut games The Bible, Can of Worms and Love and Death were 1Kb exercises in the surreal. In Can of Worms players used whoopee-cushions to give a wheelchair-bound Hitler a heart attack, performed vasectomies and tried to guess how much water would empty the King’s blocked loo.

“They were piss takes, at least as good as what else was on the market in the early days but turned inside out. The themes were overtly stupid with a bit of propaganda chucked in,” said Croucher. “The Sunday People accused me of peddling pornography to kids. Great publicity.”