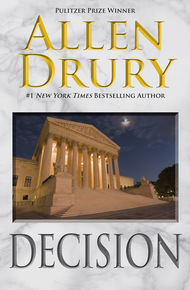

Allen Drury is a master of political fiction, #1 New York Times bestseller and Pulitzer Prize winner, best known for the landmark novel Advise and Consent. A 1939 graduate of Stanford University, Allen Drury wrote for and became editor of two local California newspapers. While visiting Washington, DC, in 1943 he was hired by the United Press (UPI) and covered the Senate during the latter half of World War II. After the war he wrote for other prominent publications before joining the New York Times' Washington Bureau, where he worked through most of the 1950s. After the success of Advise and Consent, he left journalism to write full time. He published twenty novels and five works of non-fiction, many of them best sellers. WordFire Press will be reissuing the majority of his works.

Back in print! A gripping novel about the deterioration of the criminal justice system and the mysterious, powerful body at its core—the Supreme Court of the United States.

Earle Holgren—murderer, terrorist, lost soul—is the center of a vortex that sweeps up a fascinating cast of characters in their ambitions, politics, honor, and scandal. From the eight Justices of the Supreme Court, to the Attorney General of South Carolina who sees a compelling, controversial trial as an opportunity for demagoguery that might pave his path to the White House, to the idealistic defense lawyer who seeks to save a man she knows to be a psycopathic killer, to a driven Washington journalist in love with one of the Justices whose marriage is crumbling, and other Justices with their own agendas, vendettas, and secrets.

Decision is a sweeping tale that begins at a nuclear power plant in South Carolina, works its way through the courts of that state, and finally to the halls of the Supreme Court. From the master of spellbinding political fiction, author of Advise and Consent.

When Justice Scalia passed away, most Americans assumed that every decision rendered by the Supreme Court would end in a tie. Turns out that even if you have nine Justices, ties are common if one recuses himself. That's the scenario in Decision… what constitutes a conflict of interest, and what's enough to take yourself out of a case because you can't be objective? The reader gets to follow the personal drama that plays out with one of the Justices… and his literal life and death decision. – Nick Harlow

1

The jogger came around the bend in the mountain road shortly after nine, as he had almost every morning since work on the plant had entered its final stages.

He broke stride. Stopped, hands on hips, to survey what they were doing in the valley below. Studied it all carefully for a moment. Tossed his usual grin, wave, thumbs-up.

They returned his greeting cheerfully. Someone yelled, "Hey, man!" as someone always did.

Then he resumed stride and jogged on by as he had a hundred times before.

After he was gone the day crew—as distinct from the night crew, whose members sometimes saw him more often—retained their usual distant impression of an individual: stocky, open-faced, pleasant, amiable. No one to notice, particularly; no one to stand out in anybody's mind as worthy of any particular attention. Not the sort you would turn to look at twice.

Or even once, for that matter.

The kind of face that gets lost in a crowd.

An ordinary guy.

So passed—and would continue passing until his objective, now a handful of days away, was achieved—Earle Holgren—or Billy Ray Holgren, or Billy Ray, or Holgren Williams, or William Holgren, or Henry McAfee, or McAfee Johnson, or Everett Thompson or Everett Ray.

You could take your pick, he thought wryly, a sudden grim little smile that would have much surprised the workers at Pomeroy Station Atomic Energy Installation slashing his pleasant expression with startling savagery for a moment. He didn't much care, as long as he wasn't caught.

Not that there was anything pending right now for which he should be caught—at least not anything that he recognized. Actually, he supposed, he was on the run as he had been for more than a decade, but in his mind he saw it as simply exercising reasonable caution in the face of the monstrous unfairness and injustice of the system.

He had a date with that system, and in one way or another he had been keeping it ever since college. Up to now only a few of his countrymen had been aware that he had this date. Very soon, he promised himself with a happy inward convulsion of glee so intense as to be almost sexual, the whole world would know.

He jogged on through the bright May morning, the air still benign and mellow, not yet far enough into the day to be stifling, the scent of pines and firs and lush mountain growth everywhere around him. Birds sang, rabbits scurried, two deer sprang startled across the road. No one else was there, no cars, no other joggers. The only indication of man was the distant sound of jackhammers, the echoing call of distant voices, the groan of a climbing truck. Only a man spoiled this perfect place. A sudden blind anger replaced the convulsive joy. Man! How he ruined everything.

More specifically, how Americans ruined everything. A scarifying contempt for his fellow citizens replaced the anger. Americans and their arrogant uncaring, Americans and their crude disinterest in everything that made life beautiful and worth living, Americans and their greed!

The moods of Earle Holgren were as shifting as the wind but they always came back to a basic rage against his country and his countrymen.

They didn't deserve what they had.

They were so stupid—and so overbearing—and so wanton with the infinite bounty the Lord had given them.

Such was the basic thrust of the education his generation had received. It was no wonder some of them felt themselves appointed to correct all this. And it was no wonder, given all the weapons and clever processes an industrial society so lightly left lying around, that some of them became instruments of death.

So here he was at thirty-six, child of wealth, veteran of the Sixties and early Seventies, one who had never compromised, one who had never come in from the cold—one who had managed to carry with him into new and changing decades the unchanged convictions of an unbalanced period and a twisted view of life in America no longer valid if it ever had been.

Some might consider this a terrifying mental weakness, condemning him to repeat until it destroyed him—and many others along the way—the pattern of a hate-sprung, unrelenting vengeance. Earle Holgren thought of it as a strength—his strength. He had to think this or go finally and completely insane.

Perhaps he was; he sometimes thought with a giddy feeling that he was floating somewhere out there with only his own iron will and eternal anger to support him. But the will was iron and the anger was eternal, and although to the great majority of his countrymen it might seem that both were far beyond the norms of rational behavior, to him they were the permanent and unyielding conditions of his life.

Because of this he had long since put aside his family and everything that had shaped him as a child. His parents, bewildered and shattered like so many by what they considered the monster visited upon them unjustly by inexplicable fate, had long since ceased their futile attempts to contact him. For nearly a decade after he vanished from their world, which he did immediately after graduating from Harvard and receiving Grandfather Holgren's quarter-million-dollar trust fund at age twenty-one, their anguished appeals were to be found among the many that filled the "Personals" columns in major newspapers from New York to San Francisco.

"Earle Holgren, we love you and need you. Please call. Mother … Earle Holgren, please contact Father at Blue Ridge House… Earle Holgren, Happy Birthday. We love you. Mother, Father and Sis.…" And finally the last resort: "Anyone knowing whereabouts of Earle William Holgren, formerly Greenwich, Conn., please notify A. J. Holgren, 'Seaswift,' Greenwich. Ample reward."

He had seen a few of these, for he and his companions got a perverse pleasure out of following the scraps of broken parental hearts that surfaced so often in so many publications in those years. Once in a while there was a great surge of yearning, a sudden return to childhood simplicities, that almost prompted him to answer; but each time he put it sternly aside and felt that he became stronger. Finally there was no responsive emotion in his heart at all. He was satisfied at last that that part of his life was dead.

Once in a great while this brought a disturbing aftermath. Perhaps other things were dead too? Perhaps everything was dead? Perhaps he was a zombie with nothing left to hold on to, no center to his life, nothing inside at all.

But this too he put sternly aside on the very rare occasions when it troubled him. Although many of his old companions dropped away, seduced back by the more conventional rewards of the system, still there were some who remained; and although the riots, the protests, the robberies and bombings had also dropped away for a time to almost nothing, still there were a few, enough to bolster his feeling of still belonging to a cause beyond himself. And now in the last several years violent protest had begun to revive, washed along on the rising tide of economic unrest, inflation, the swift burgeoning of all kinds of crime, all across the country. Violence, never very far away in the land of handguns and economic uncertainty, was becoming king again. And the great cause of righting the wrongs of American society could still be pursued. The endless (if endlessly disappointed) quest to bring perfection to an imperfect country was still worthy of a heart's devotion, a lifetime's dedication.

America—the America of his parents, the steady, decent, respectable, good-hearted America that had been, and remained, the ideal of so many—was becoming terrified. The steadily rising crime rate of the Seventies had surged ever higher into the Eighties, and with it the opportunity for such as he to return to the violent forms of protest that were the most satisfying because they were both frightful and usually impersonal enough in execution to free him from any feelings of direct personal responsibility.

Thus his mind could retain the serene certainty of its own righteousness—his only, but impregnable, shield against the violent horror of his age—and against the fact that he himself had made his own substantial contributions to those horrors in these recent years.

Grandfather Holgren's trust fund was still in excellent shape—he of course had never paid income tax on it, which was one of the charges society had outstanding against him—and with the aid of a lawyer in New York friendly to him and others of his kind he had made a series of carefully hidden investments that had actually increased it substantially. Thus supporting himself was no problem. It was also no problem to support Janet, with whom he had lived for the past three years, and little John Lennon Peacechild, who had come along a year ago to intrigue and interest him in a remotely unconnected sort of way. They could live where and as they pleased—underground and modestly, of necessity, but very comfortably for all that.

He was approaching the end of the road. It terminated at an old deserted mine shaft set into the hillside. So woods-wise had he become as a youngster in these same hills, when they used to come down each summer to what his father called "Blue Ridge House," that there was no sign visible to the casual passer-by that the entrance to the shaft had been disturbed since the vein petered out sixty years ago. Not even a woodsman as experienced as he could tell without very close examination that certain logs and brush, a little too carefully distributed, hid the small cave that opened just to the left of the entrance and curved back into the hillside. Part of it had once been used for storage and that was what he was using it for now; but unless someone really suspicious had a really urgent motivation to find it, the chances were that no one ever would.

And there was no one really suspicious in his world as he had presently created it. Janet was as placid as a cow, having gone through all the expected stations of the route to salvation as a certain segment of their generation saw it. She had smoked, sniffed, snorted, main-lined, finally done the conventional and turned to alcohol. Now she lived in a gentle haze, mouthing all the old slogans dutifully when prompted, paying less and less attention to causes, more and more to John Lennon Peacechild, whom she obviously regarded as the best trip of all, the very best she had ever been on. She seemed always mildly drunk, never seemed to want to leave the cabin, always seemed content to hover around the child, which was fine for his purposes because he didn't want her hobnobbing with the neighbors anyway.

The old virtues, he sometimes told himself with an ironic inward smile, had reclaimed Janet with a vengeance. Next she would want to formalize it all with a wedding ring, which he wouldn't give her because that would also give her a legal claim on his inheritance, and that he was not about to give anybody. It was all very well to advocate sharing, but what was his was his and no washed-out hippie was going to run off with any of it. Like everything in his world, Janet was a convenience (and John Lennon Peacechild an accidental, mildly interesting dividend). As long as it suited him, they would remain. When they became a bother—or a danger—or he got sufficiently bored—he would get rid of them and that would be the end of it.

He stood for a moment listening. Now the distant agitations at Pomeroy Station were too far away to be heard at all. No human sound broke the busy mountain silence. The wind sighed gently in the trees, jays screeched, a crow spoke crossly somewhere in the high branches, four more deer sprang away startled at his approach. He looked carefully all about, held himself rigidly listening for a measured minute. With a sudden pantherlike stealth that suited the mountains, he was at the mine-shaft entrance. Logs and brush were swiftly pushed aside. He reached in, dropped something, as swiftly replaced his careful camouflage, stepped back from the entrance and stood, hands on hips again, as though he were studying it with an interested curiosity for the first time.

Charade completed, he shook his head as though in amused puzzlement, turned and came back to the circular area where the road ended. He jumped up and down several times, slapped his arms across his chest, jogged in place for a moment or two and then started off down the road again as casually as he had come.

In Washington, D.C., far from the gently rolling foothills of the South Carolina Blue Ridge, others were also considering the condition of the country and their own responsibilities toward it. They were not finding it so easy to analyze and prescribe for as Earle Holgren did. Much sooner than he expected—and they of course had no way of expecting it at all—they would find Earle Holgren in their lives. They would also find the present Secretary of Labor, Taylor Barbour. The encounters would be fateful for all concerned, and for a society greatly troubled by the constant escalations of crime and violence.

For the time being, however, the unique and highly individualistic group that worked in the stately white marble building facing the Capitol across the greensward of Capitol Plaza had a wider concern, its implications not yet narrowed down to the specific of an Earle Holgren. Their canvas was infinitely broader: and today, as they gathered for their usual Friday conference to clear up the odds and ends that remained before scheduled June adjournment, the eight Justices who for the moment comprised the Supreme Court of the United States were more deeply concerned than they had been in a long, long time.

"Not since civil-rights days," Clement Wallenberg remarked after they had exchanged suitable small talk.

"Not since ever," Rupert Hemmelsford responded glumly as they took their seats around the long table in the comfortable antique-filled Conference Room just across the hall from the formal Supreme Court Chamber.

"In fact, my sister and my brethren," the Chief Justice said, employing the quaint verbal usage with which Supreme Court Justices actually do address one another on many occasions formal and informal, wry or serious, "if things keep up the way they're going, I expect we're in for one hell of a time. There must be a dozen cases on the subject already in the courts below, waiting to come up to us."

"If we accept them," Waldo Flyte pointed out. "We don't have to grant them certiorari. Nobody can force us to consider anything we don't want to consider. We can always sidestep the issue." He winked cheerfully. "We've done it before."

"Not if growing criminal violence continues to provoke increasingly violent response from the citizenry," the Chief, whose name was Duncan Elphinstone, said with some severity. "We can't evade our clear duty, Wally, and you know it."

"The trend isn't going to stop unless we stop it," Mary-Hannah McIntosh agreed with equal severity, inclining her close-cropped gray head to one side and peering over her pince-nez at Justice Flyte.

"Not if things continue the way they're going in your state," Moss Pomeroy remarked, half teasing her as he liked to do, but pointedly. She flared, as always, in defense of California.

"South Carolina shouldn't talk! Things are getting rough down there, too."

"Rough everywhere," Raymond Ullstein observed of his own state with an unhappy air. "New York City continues to trail Los Angeles in violent crimes and violent deaths, but only just. Only just."

"It's all over the country," Hughie Demsted agreed glumly. "Three hundred and seven murders in the District of Columbia already this year. Mostly involving my own people, too, God help us."

"And the majority of them everywhere so God damned pointless," Wally Flyte observed with a frustrated anger. "Just killing for killing's sake. Ten dollars stolen here, and just for extra kicks they waste the victim. One car brushes another, quite accidentally, so they shoot each other down in the street. An old lady's purse gets snatched, with no possible response from her, so they beat her head in and leave her dead in the gutter. A perfectly innocent dinner party steps out of a restaurant and three insane no-goods gun them down. Rape, robbery, murder, destruction—just for the hell of it. What in the hell is the matter with this crazy damned country, anyway?"

"Lack of adequate gun laws," Justice McIntosh said promptly, seizing the chance to open one of her favorite topics.

"The pointless and inexcusable death penalty," and "The lack of a sufficiently tough death penalty," Justice Ullstein and Justice Pomeroy said together, each from his own point of view seizing upon their mutually favorite topic.

"I believe," Duncan Elphinstone said, drawing up to its full and quite sufficient dignity his five-foot-four frame (which since childhood had inspired the nickname "The Elph," mentally spelled "Elf" by all who used it), "that this Court must inevitably come to grips with the matter of ravenously proliferating, wantonly murderous crime, and very soon. We did indeed, as you so charitably put it, Wally, 'sidestep' it in the last two terms, but very soon we've got to meet it head-on. Or the country, as has sometimes happened in the past on some other issues on which the Court has dragged its feet, is going to take matters in its own hands. In fact, it's starting to already. We're right on the verge of revived Vigilante Committees, a real resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, the paraphernalia of 'law and order' about to be taken right out of our hands by a fed-up citizenry. Under the Constitution we're the supreme law and order in this land, and I think we'd damned well better get to it."

"You sound like Mr. Dooley, Dunc," Rupert Hemmelsford remarked, but affectionately. "You want us to follow the 'iliction returns.'"

"Part of our function," The Elph reminded him, "is to head off the worst before it can happen. That function has never been more important than it is right now in the area of crime. You mentioned California, Moss. Look at California!"

"And I must admit, as Mary-Hannah says," Justice Pomeroy said ruefully, "look at South Carolina too. Are you aware there's a real, genuine move afoot in my state to revive flogging—on television? And hold executions—on television? And punish even the smallest of crimes—even if a guy feels he has to steal bread for his family, let's say, because the economic situation is so bad right now—with an upgrading of penalties that would put it in the category of major crime? And the people are beginning to want this. All sorts of demagogues are trying to whip them up. It's getting positively Islamic. Jesus! It scares the hell out of me. Even if"—and he winked at Ray Ullstein—"I do want the death penalty. Within reason, I want it. I'm not medieval."

"It scares me, too," Mary-Hannah said soberly. "What's the name of your fellow down there?"

"Regard Stinnet," Moss said, "pronounced Ree-gard. He's state attorney general right now, but he wants to be governor—Senator—President, I suppose. The sky's the limit with that boy."

"We have a pretty busy one, too, you know," she said. "I hate to admit it, but he's on the same track. Also state attorney general, also a demagogue, also on his way to the stars—he thinks. Ted Phillips, our boy is."

"They aren't alone," Justice Wallenberg observed. "It's catching on all over the country right now."

"People are just God damned fed up, that's all," Moss Pomeroy said. "You can't blame 'em. The whole criminal justice system is getting out of whack—and not without some assistance from this Court in recent years, I might add. To be honest about it."

"Well," Clement Wallenberg said, "I wasn't on it then—"

"Neither was I," Moss said promptly. "Neither were most of us. But we're the inheritors. It's called 'the continuity of the Court.'"

"But not necessarily 'the consistency of the Court,'" Justice Ullstein suggested with one of his rare gleams of humor.

"That is another matter," Justice Hemmelsford said, making the ineffable gesture that the AP's reporter at the Court referred to as "blinking his eyebrows," and peering about at them with his customary sly twinkle.

"They used to call slavery 'the peculiar institution,'" Clem Wallenberg remarked, "but I swear if there's any more peculiar institution than ours, I don't know it."

For a moment they were silent, contemplating the strange nature of the Supreme Court which, developing gradually over two centuries under first the actual, then the historical and legendary, tutelage of Chief Justice John Marshall, had given them so much power of so strange and tenuous, yet so persistent and generally unassailable a kind, over their country's destinies.

"Well," Duncan Elphinstone said, breaking the mood. "I expect we'd better get down to business and start voting on these appeals for certiorari. There's already a case from Minnesota that's pertinent to our discussion, but maybe we'd better take things in order. First comes Cincinnati Taxpayers v. Internal Revenue Service. What shall we do with that one?"

So for a couple of hours they discussed Cincinnati Taxpayers v. Internal Revenue Service and some fifty other cases, a few of which prompted as much as ten minutes of discussion, but most of which were voted up or down with none at all. When they adjourned for lunch, which they elected to take together today in the Justices' cozy formal dining room on the second floor, the nagging topic with which they had begun came back again, complicated further by a rumor that had just come in to the press room downstairs on the first floor. As reported by the UPI, it said that the enigmatic gentleman in the White House was about to nominate, probably that very afternoon, someone to fill the current vacancy created by the retirement of Homer Dean and thus restore the Court to its full nine-member capacity.

Earle Holgren jogged slowly back down the winding road, assuring himself with a smug satisfaction that it was his ability to be casual and at ease with what he did, his characteristic of being visible but at the same time so ordinary as to be virtually unseen, that had made him so successful in the activities for which the unjust system really wanted to bring him in.

Thinking of these now as he trotted along, the sounds of Pomeroy Station at first faint then louder as he approached the plant again, he congratulated himself that he had never once failed to achieve his objective in the permanent war that he and a small handful of companions still waged against their country.

He had disappeared occasionally, without explanation to Janet or anyone. During the course of his absences four banks were robbed, seventeen people died in an airport bombing in Illinois, twenty-five more in the sinking of a ferry near Seattle, sixteen in a children's parade in California. Travel was no problem, easy targets in a still-innocent, open society, were everywhere. He had by now become a very skillful expert in demolition. Along with buildings and people, he was still hoping to demolish the society. He was part of the growing mood of fear and uncertainty that fastened increasingly upon his countrymen, and proud of it.

The only thing that annoyed him considerably, he reflected as he swung down again past Pomeroy Station, gave its workers and guards a parting wave and jogged on by, was the fact that his type of protest now was not unique: much of its calculated impact was lost in the general tide of wanton crime. Violence was satisfying to those who felt they were doing it in some great social cause whose rationale only they were privileged to understand; but when robberies, rapes, molestations and wanton casual killings in public streets and private neighborhoods were becoming so prevalent, the statement seemed to be disregarded—quite disrespectfully, he felt—in the general public fear and agitation.

Everybody was getting into the act nowadays: killing for killing's sake was becoming an American habit. He wondered wryly sometimes whether it was worth making a personal effort to bring the society down. It was being consumed quite adequately, many of his countrymen felt and he sometimes agreed, from within.

Yet there must still be room for someone to make the point he wished to make—whatever it was. His alienation from society had been so conventional in terms of the Sixties and early Seventies, so predictable in all its stages from the student protests to the breaking with his family, to his disappearance, to the underground conspiracies, to the robberies and bombings, all in the name of the greatest good for the greatest number, that he had to continue to play out the charade now and never yield to uncertainty. Otherwise his whole life's meaning would be destroyed. He could not have endured this. He just had to go on, destructive and essentially mindless for all his intelligence and cleverness, repeating the past because there was no way for him, now, to find the future.

Of course he could not admit this. He was the future. He had a purpose, he had a goal—he destroyed society in order to save it—he knew the secret. He felt a complete contempt for the animalistic committers of animalistic murders who now befouled the land, the primitives who roamed the streets and slaughtered on a second's sick impulse. He was infinitely better than they. He was Earle Holgren, guardian of a Cause. And after he had defended it at Pomeroy Station, there would no longer be doubt of it.

The target he had chosen this time was an obvious one, given his lifelong familiarity with the area and the fact that even now, after years of agitation, security at the nation's atomic energy plants was still as lax and casual as ever.

He jogged on down the mountainside for another three miles until he came to the outskirts of the little village of Pomeroy Station, turned off the paved road onto a dirt lane, came presently to the modest cabin isolated among the pines. Janet was sitting idly in the sun, crooning some sort of rambling lullaby to John Lennon Peacechild, who was sleeping sprawled across her by now considerable lap.

"Have a good run?" she asked idly.

"Yes."

"Go by the plant?"

"Don't I always?"

"You really like that old plant," she remarked, still in the same idle way.

"What makes you think so?" he demanded, suddenly sharp; probably not a good idea, but she was too dumb to notice.

"You're always hanging around there."

"I do not 'hang around there,'" he said with a measured emphasis, "so forget it."

"Okay, okay," she said mildly. "Just noticing."

"Don't notice. People get hurt noticing."

"Okay," she said, finally sounding a little alarmed by his tone. "You don't have to take my head off. What are you going to do now?"

"Study," he said as he started into the cabin.

"You're always studying," she protested with a half-scornful laugh. "Anybody'd think you were going to be a lawyer, or something."

"Maybe I will," he tossed over his shoulder. "The world could stand a few good ones who believe in doing the right thing. There aren't too many of that kind who really care for the people."

"Lucky they have you," she retorted dryly. He stopped dead, turned on his heel and came back to the doorway.

"Don't be so God damned smart," he snapped. "I tell you, people get hurt like that."

"Just commenting," she said, retreating into the kind of shrugging indifference she showed when he lost his temper: which was more often as the appointed day approached. "You're getting awfully touchy, lately. Worried about something?"

"No, I'm not 'worried about something'! What would I be worried about?"

"I don't know," she said, turning to nurse John Lennon Peacechild, who had been awakened by his father's angry tone and was beginning to cry. "And," she added spitefully, "I don't care."

"Keep it that way," he said and turned and went in, slamming the flimsy screen door behind him.

There was silence except for an occasional pleased gurgle from the baby.

Just get over the next couple of weeks, he told himself.

Don't fly off the handle.

Don't get her curious.

Just keep it cool.

Keep it cool.

It was the only way.

"It doesn't say," the Chief Justice remarked when he finished reading the wire-service copy his chief clerk had placed discreetly in his hand as they entered the dining room, "whom he has in mind as our new Associate. Or"—he smiled at Justice McIntosh—"what gender. Next thing we know, we may have to establish a ladies' gym."

"I wouldn't mind the company," she said, "but I don't remember any speculation about a female appointee in the last few days. I think you men can continue to lord it over me."

"That will be the day!" Hughie Demsted exclaimed with an amused shake of his handsome black head as they took their seats informally around the dining table. "I thought Archie Gilbert of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals was the front-runner, Dunc."

"Sue-Ann and I were at Henry Randall's last night for dinner," Justice Pomeroy said, naming the shrewd legal mind who was senior Senator from Virginia and chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, "and the guessing there seemed to center around Taylor Barbour. For what it's worth."

Rupert Hemmelsford, who had been chairman of Judiciary himself before his appointment to the Court, blinked his eyebrows and assumed the disapproving look he got when contemplating the highly intelligent, highly effective, much-publicized forty-six-year-old Secretary of Labor. "Henry's a good weathervane," he said, "but I'm not so sure I can work very well with Tay Barbour. I don't anticipate he'll have any trouble with Senate confirmation, though. I'd guess two days of hearings and confirmation by about seventy to twenty-six, wouldn't you, Wally?"

"Higher than that," Justice Flyte said with a calculation harking back to his own Senate days. "More like eighty to seventeen, I hear. Tay has some problems, but I don't think they lie with the Senate."

"Things are running down with that marriage," Justice Wallenberg observed with characteristic bluntness. "It could affect his work as a Justice. It's not unheard of, in Court history."

"He'll subordinate it to the Court," Mary-Hannah suggested. "He won't let anything disturb his work here."

"You like him," Rupert Hemmelsford said, his tone almost an accusation. She nodded briskly.

"Very much, Rupe. Shouldn't I?"

Justice Hemmelsford sniffed. "You liberals always stick together."

"And you conservatives don't?" she inquired. "Anyway, you know this institution, Rupe. Today's liberal is tomorrow's conservative is next day's liberal is next day's conservative—you know how it goes."

"That's one of the great things about us, isn't it?" Hughie Demsted agreed with a grin. "Nobody can tie us down, not even our own past records. Once we come on this bench there's not a soul on earth can control us or be absolutely sure what we're going to do. That's one of our great strengths—infinitely better to have us sitting up here a bunch of unpredictable independent mavericks than it would be if we were just a gang of puppets for some transient in the White House. Right?"

"He wouldn't like to be referred to like that," Rupe Hemmelsford said with a chuckle. "Like all of 'em, he's got the idea he's eternal. Whereas in reality"—he gave his sly grin—"we are. But you're right, of course. It keeps him wonderin' and hoppin'."

"Which is all to the good for the country," Hughie Demsted said triumphantly, settling back to take a sip of his coffee. "If not, Ray, the law."

"The law has got to be consistent if it's to mean anything," Justice Ullstein insisted with his quiet stubbornness that often achieved more than another man's flamboyant dramatics.

"We're the law," Moss Pomeroy said with his usual irreverent grin, "and we're not consistent, half the time. So how can the law be?"

"It's got to be," Ray Ullstein said doggedly. "Or at least we've got to try to make it so. We've got to subordinate our personal feelings and problems, as we were saying about Tay Barbour earlier, to the needs of this Court."

"Well," Justice McIntosh said with some dryness, "we're important, all right, but I don't know that we're all that keeps the country from drifting. There's a whole complex of things—tradition, old habit, respect for and devotion to the Constitution, a basic respect for law and order among the great majority of our countrymen—"

"Who are about, as Dunc says, to take the law into their own hands and raise counter-hell with everything," Wally Flyte remarked dryly.

"Listen!" Justice McIntosh said, as sternly as though she were still dean of the Stanford Law School, which she had been for five years before her appointment to the Court. "Don't lecture me on the situation in this country! I know what it is. I also know that not an hour ago we voted five to three to deny certiorari to Evans v. Minnesota, a very pertinent case, and it wasn't my vote that kept us from considering it. The Chief asked us to face up to it. Well, we just didn't. What is it going to take?" she demanded with a concluding burst of indignation. "Will one of us, or somebody near us, have to be slaughtered or mutilated or something, before we come to grips with it?"

"Well, now, May," Dunc Elphinstone said soothingly, figuring it was time, as Rupert Hemmelsford often put it behind his back, "to spread on a little of the old snake oil," "I don't think we need to get personal about things. It's bad enough, as we all know. I'm hopeful," he added with a slight asperity that indicated he, too, was becoming impatient, "that in the next couple of weeks we'll find a case we can all agree on, grant it certiorari and get to it. We can't fiddle around much longer."

"I'm ready," Justice Wallenberg said, returning his gaze with a calm and unimpressed air. "But it's got to be a good case, not one we have to stretch for. Maybe South Carolina"—he turned and bowed sarcastically to Moss Pomeroy—"will provide us with something. It's already given us the Court dude."

"Clem, God damn it," Justice Pomeroy said, "will you stop sniping at me? I'm sick of it! Sick of it! Just because I have thirty years on you—or is it a hundred?—and a beautiful wife and lots of money and smashing good looks"—he began both to exaggerate and soften his tone and his usual charming grin began to break through—"and you're just a sour, wizened, nasty old sourpuss who's a liberal-conservative or a conservative-liberal or some kind of all-purpose Push me-Pull you for the Court—anyway," he concluded cheerfully as they all, even Clem, started to laugh—"what the hell are we talking about? The whole thing is too serious to fight over in chambers. Why don't you all come down to South Carolina and be my guests, and we can relax and forget it for a day?"

"What's the occasion?" Justice Wallenberg inquired in a still slightly prickly, but mollified, tone.

"They're dedicating the Pomeroy Station atomic energy plant," Moss said, "and you know why I'm involved. It's out west in the Blue Ridge on what was the original Pomeroy Grant in 1693, although we haven't owned the property for at least a hundred years, I guess. But because my name's still on it, and because I was governor when they started to build it, they want me there. I'd like to invite you all, if you'd like to come."

"Against atomic energy," Clem Wallenberg said shortly. "Wouldn't be caught dead."

"Scratch one," Justice Pomeroy said with unfrayed cheer. "I'm just as relieved as you are, Clem. Any more cop-outs?"

The Chief hunched forward and clasped his hands under his chin with a thoughtful air.

"As a matter of fact," he said, looking up and down the table, "we've already had some cases on the atomic issue, as you know, and inevitably we're going to have more. I really think it might be better if we all passed. With all thanks and respect to you, Moss. Does that make sense?"

There were unanimous nods and sounds of agreement.

"Now let me offer a counterproposition. Birdie and I would like to have everyone to dinner a week from next Friday. Just to wind up the session, as it were. And to officially greet Tay and Mary Barbour, assuming he's nominated and confirmed by then, as our two distinguished ex-Senators predict."

"That's the night of my trip to South Carolina," Moss said, "but the ceremony is at noon and Sue-Ann and I will be coming right back. The President's giving us a plane."

"Oh, I say," Justice Wallenberg remarked. "How jolly."

"Yes, isn't it," Moss agreed with a grin. "You see what you're missing, Clem."

"So, then," the Chief said, "a week from this coming Friday, eight p.m., in the dining room here, black tie—"

"God, must we?" Hughie Demsted groaned.

"You look divine, Hughie," Justice McIntosh said, "and you know it, so stop objecting. Men always look divine in black tie. Why do they always balk?"

"With spouses, of course," The Elph went on. "Or," he added, bowing to Mary-Hannah, "boyfriend, as the case may be."

She hooted.

"Darling," she said, "I am fifty-eight years old, in the sere and yellow leaf, and the last time I was unfurled was—" She stopped, blushed and started to laugh, as did they all.

"When, May?" Moss Pomeroy demanded eagerly. "Oh, do tell us about it! When? When?"

But she had collapsed in laughter and so their luncheon ended on a merry note as the Chief said with mock sternness, "And now, back to those damned certioraris. We'll be lucky if we get out of here by six p.m."

"I'm afraid so," Wally Flyte said, heading for the door. As he reached it there was a knock and it was opened from the other side so quickly that it almost hit him in the nose. A clerk thrust a piece of wire-service copy into his hand with an apologetic murmur and fled. Wally glanced at it hastily and spun around, holding it high.

"It's Tay," he confirmed. "By a landslide."