Kristine Kathryn Rusch writes in multiple genres. Her books have sold over 35 million copies worldwide. Her novels in The Fey series are among her most popular. Even though the first seven books wrap up nicely, the Fey's huge fanbase wanted more. They inspired her to return to the world of The Fey and explore the only culture that ever defeated The Fey. With the fan support from a highly successful Kickstarter, Rusch began the multivolume Qavnerian Protectorate saga, which blends steampunk with Fey magic to come up with something completely new.

Rusch has received acclaim worldwide. She has written under a pile of pen names, but most of her work appears as Kristine Kathryn Rusch. Her short fiction has appeared in over 25 best of the year collections. Her Kris Nelscott pen name has won or been nominated for most of the awards in the mystery genre, and her Kristine Grayson pen name became a bestseller in romance. Her science fiction novels set in the bestselling Diving Universe have won dozens of awards and are in development for a major TV show. She also writes the Retrieval Artist sf series and several major series that mostly appear as short fiction.

To find out more about her work, go to her website, kriswrites.com.

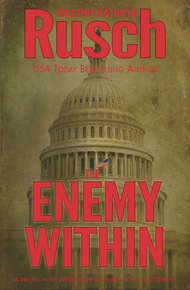

One of Kristine Kathryn Rusch's most acclaimed short stories becomes one of her most original novels.

February, 1964: Two men die in a squalid alley in a bad neighborhood. New York Homicide Detective Seamus O'Reilly receives the shock of his life when he looks at the men's identification: J. Edgar Hoover, the famous, tyrannical director of the FBI, and his number one assistant, Clyde Tolson.

O'Reilly teams up with FBI agent Frank Bryce to solve the second high-level assassination in only three months. Because in November of the previous year, someone assassinated President John F. Kennedy. The cop and the FBI agent must determine if the same shadowy organization committed all three murders. To do so, they must act quickly before some of the nation's most powerful men—from Kennedy's brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, to the President of the United States, Lyndon Baines Johnson—do something rash to keep Hoover's secrets from ever becoming public.

In our world, Hoover kept his secrets until long after his death. In Seamus O'Reilly's world, Hoover's secrets get him killed. The Enemy Within offers alternate history so plausible that only Kristine Kathryn Rusch could have written it.

Winner of the 2014 Sidewise Award for Best Long Form Alternate History.

Kris Rusch and her husband Dean Wesley Smith are both prolific writers, but also have served as mentors to countless writers, including myself. They've been the most influential in my own career and took my work to another level. This book features something I truly love: an alternate history. If you like those "What If?" books as they pertain to politics, you'll love The Enemy Within. It was voted "Best Long Form Alternate History" in 2014, winning the Sidewise Award. – Nick Harlow

"A dark, yet fascinating tale, The Enemy Within gives readers an intriguing look at what could have happened in 1964 New York."

– RT Book Reviews"Entertaining and well written."

– Gumshoe"Fast-paced from the moment the NYPD cops identify the victims, fans will appreciate this taut thriller as corruption at all levels of government leads to a need for a cover-up that makes a bad situation much worse."

– The Midwest Book ReviewOne

THE SQUALID LITTLE ALLEY smelled of piss despite the February cold. Detective Seamus O'Reilly tugged his overcoat closed and wished he'd worn boots. He could feel the chill of his metal flashlight through the worn glove on his right hand.

He had been working swing shift since Kennedy's assassination almost three months before. He'd volunteered. He wanted the night murders—the muggings gone bad, the 3 a.m. domestic tragedies, the knifings after last call—because he knew day shifts would get protection duty and the political cases. New York got its share of dignitaries, and after Dallas, all of them were afraid they'd be next.

He wanted straightforward crime, not babysitting so-called famous people. The kids were grown, and with Nola working nights at the hospital, swing seemed best for him as well.

Except at moments like this, when he stood next to a coroner's van outside a dirty little alley, and that feeling in his gut, the one he'd learned to trust at Anzio twenty years ago, flared so badly that he wanted to turn around and go home.

Instead, he glanced over his shoulder to make sure his new partner was behind him.

Joseph McKinnon was ten years younger, twenty pounds lighter, and six inches taller. He had the thick neck and broad shoulders of a former quarterback, and an all-American handsomeness that should have kept him out of undercover work. But it hadn't; he'd been one of the best vice cops in the city, and, as a promotion, he'd asked for homicide.

McKinnon was just beginning to learn that homicide wasn't really a step up. O'Reilly was just beginning to learn that having a new partner didn't mean he had a better partner.

McKinnon was looking at the surrounding buildings, his flashlight pointed down. The street was dark and empty. Which was not a surprise. Police presence made anyone who lived on this block vanish.

This neighborhood teetered between swank and corrupt. It was far enough from Central Park for degenerates and muggers to use the alleys as corridors and, conversely, close enough for new money to want to live with a peek of the city's most famous expanse of green.

So far, the new money hadn't overtaken the old ways—at least, not on this block. O'Reilly had handled four murders here since he transferred, but all of them were on the street itself, the bodies found by cops or delivery men. Someone in the alley might not get found for days.

On this block, most people looked the other way. One block north, they started watching out their windows. On the block across from the park, they might actually call the cops if they saw something going down.

But in this alley, it was amazing anyone had found the bodies at all.

Unlike the street, the alley wasn't dark. It looked like daylight in the small rectangular space. The coroner had set up his trademark battery-operated lights on garbage can lids placed on top of the dirty ice, one at the head of the bodies, the other near the feet.

O'Reilly wasn't going to look at the bodies—not yet. He liked to absorb the scene first. Sometimes, these few moments yielded the most important information. Impressions, feelings, seemingly small details often led him to the heart of any case he was working on.

Which was why he had one of the highest closure rates in the department, and why his bosses had fought his transfer to nights so hard.

The lights created crisp shadows on the brick walls. The two beat cops who had discovered the bodies were standing near the front of the alley, their shadows elongated and thick. The coroner's assistant stood behind one of the lights, next to the gurney he'd brought, so his shadow looked like someone had painted him in black. It was an eerie tableau, made eerier by the fact that the coroner—in the middle of the lights—had no shadow at all.

Thomas Brunner, the coroner, bent over the bodies. O'Reilly liked working with Brunner. They were the same age and had the same attitude toward work: Get it done, do the best job possible, and move on. Most everyone else in the department disliked Brunner. He was blunt, bigoted, and hard-nosed.

But he never messed with O'Reilly. They'd had a run-in the very first time they'd worked together—1946 or '47—right after both of them had come back from the war. O'Reilly's temper—hot, sudden, and violent—had won the encounter, but his willingness to forgive and forget had made the two of them if not friends, then at least amicable colleagues.

O'Reilly stepped into the alley proper. His dress shoes slipped on the ice, and he had to catch himself so that he wouldn't fall. Most of the sidewalks in the city were clear—a week of unusual warmth before this had guaranteed that the snow and ice would melt—but apparently the sun never got to this corner of the city.

And somehow that didn't surprise him.

The bodies, male and well dressed, sprawled side by side. They rested on their stomachs, heads facing north, arms bent as if they tried to catch themselves. One leg on each body was straight, the other bent at the knee, like the old white chalk images of dead bodies in black-and-white movies.

The entire thing looked like a movie set—like this neighborhood had looked not five years before when some Hollywood types filmed the exteriors for West Side Story. That had been one of the few times he hadn't minded doing protection—until he realized just how dull film-making could be.

He squatted beside Brunner. The dead men were white and fleshy, with manicured fingers and expensive wool coats. Too well dressed for this neighborhood. Maybe they'd walked down the wrong block.

Although that didn't explain how they got into the alley.

Their faces were mashed into the ice, their features distorted from the force of the impact. He wouldn't know what they really looked like until Brunner turned them over.

Clearly Brunner wasn't ready to do that. He was using his gloved hands to press lightly on the back of the corpse closest to him.

"What've we got?" O'Reilly asked.

"Dunno yet." The pressure from Brunner's hand caused blood to well out of a hole on the body's left side. The shot was perfect. It would have gone directly through a rib and into the heart.

"Looks like a good shot," O'Reilly said.

"Good shot, yeah," Brunner said. "Single shot. Matches the one on his friend here. They both died instantly."

"You sound unhappy about that."

Brunner kept his hand on the corpse's back, but looked at O'Reilly. Brunner was balding, his face whitish gray in the strong light.

"You see as many bodies as I do, you realize how rare it is for anybody to receive a perfectly made kill shot, let alone have two anybodies right next to each other get the exact same shot."

O'Reilly leaned forward. He didn't touch the bodies—he didn't have to—but he could see the blood soaking the other corpse, and the hole in the exact same spot as the one Brunner had just found.

"Christ," O'Reilly said. "You think these guys were targeted."

"I'm hoping." Brunner looked at him sideways, expression tight.

O'Reilly wasn't sure he'd heard Brunner right. "You're hoping they were targeted?"

"Damn straight. Otherwise we got a problem."

O'Reilly frowned, not quite following Brunner's point. At that moment, McKinnon came into the alley. He shined his flashlight on the darkened windows of the southern building's upper story.

Sometimes O'Reilly didn't understand his partner. Any more than he was understanding Brunner at the moment.

"What kind of problem?" O'Reilly asked.

"This ain't the only call I've had around here tonight."

"Really?" O'Reilly asked. "What else we got?"

"Some colored limosine driver shot a block from here." Brunner pressed on the back again. The blood stopped seeping. This corpse had to have a heck of an exit wound. "And two white guys pulled out of their cars and shot about two blocks from that."

O'Reilly felt a shiver run through him that had nothing to do with the cold. A limosine driver? Two white men pulled out of cars? Brunner was right; if these killings were random, then O'Reilly had a hell of a problem.

He asked, "You think the shootings are related?"

"Dunno," Brunner said. "But I think it's odd, don't you? Five dead in the space of an hour, all in a six-block radius."

O'Reilly closed his eyes for a moment. Two white guys pulled out of their cars, one Negro driver of a limosine, and now two white guys in an alley. Maybe they were related, maybe they weren't.

He opened his eyes, then wished he hadn't. Brunner had his finger inside a bullet hole, his favorite in-the-field way to judge caliber.

"Same type of bullet," Brunner said.

"You handled the other shootings?"

"I was on scene with the driver when some fag called this one in."

O'Reilly looked at Brunner. Eighteen years, and he still wasn't used to the man's casual bigotry.

"How did you know the guy was homosexual?" O'Reilly asked. "You talk to him?"

"Didn't have to." Brunner nodded toward the building in front of them. "Weekly party for degenerates in the penthouse apartment every Thursday night. Thought you knew."

O'Reilly looked up. Now he understood why McKinnon had been shining his flashlight at the upper story windows. Everyone in vice would have known about a party like that.

But homicide didn't.

"No, I didn't know," O'Reilly said. "No reason I should either."

"I thought everyone knew," Brunner said.

"Why would you think that?" O'Reilly asked.

McKinnon was the one who answered. "Because of the standing orders."

"I'm not playing twenty questions," O'Reilly said. "I don't know about a party in this building and I don't know about standing orders."

"The standing orders are," McKinnon said as if he were an elementary school teacher, "not to bust it, no matter what kind of lead you got. You see someone go in, you forget about it. You see someone come out, you avert your eyes. You complain, you get moved to a different shift, maybe a different precinct."

"Jesus." O'Reilly was too far below to see if there was any movement against the glass in the penthouse suite. But whoever lived there—whoever partied there—had learned to shut off the lights before the cops arrived.

"It's gonna take forever for the scene-of-the-crime guys to arrive." Brunner looked at his assistant. "I need pictures. Then we're rolling these guys over."

The assistant, a young man that O'Reilly didn't recognize, winced. He left the gurney in the alley and went back to the coroner's van.

Pictures would help, but they wouldn't give a real sense of this scene. The alley was small. With five men in it, as there had been a moment ago, it felt crowded.

The victims would have seen their shooter. Unless he hid. And the victims were lying lengthwise across the alley, head and feet pointing toward the walls. If the victims been trying to leave the alley, they would have been lying in the alley's narrow width. And if they'd been shot in the back while leaving, their heads would have pointed toward the street.

O'Reilly rocked back on his heels. The alley didn't have much. Two metal garbage cans—now without lids thanks to Brunner—and a pile of unmelted snow against a wire mesh fence marked the back end. The north building was all brick. On this level, there weren't even windows. The windows started about six feet up and continued on all six stories.

He squinted at the south building. A door, carefully painted to mimic the brick around it, was barely visible, and there was no stoop. Whoever stepped out of that door would drop nearly a foot to the ground.

Footprints had formed in the ice from repeated use, and the footprints faced into the alley. This was an exit, not an entrance, a fact confirmed by the lack of a doorknob or handle on this side.

This building rose eight stories, and the glass windows here actually looked clean. He had a sense that people were watching from above, but that might simply have been because of Brunner's talk of the private party.

The victims had come out of that door. They had dropped to the alley floor, taken a few steps, and then gotten shot.

O'Reilly rose and walked past the lights. He crouched near the wall. The ice here was smooth. He rapped it with his gloved knuckles. It was still hard too. Someone standing here wouldn't have broken through the ice's surface.

There were no cigarette butts, no gum wrappers, no crumpled coffee cups. No sign of waiting. There weren't beer bottles either, which he found odd on this block, and no empty needles.

There were also no shell casings. He still wasn't sure of the murder weapon's caliber, so he wasn't sure if the lack of shell casings was important or not.

The assistant had come back. He was using one of those Polaroid cameras to take pictures of the bodies. The flash glared.

"Don't you have a good camera?" O'Reilly asked Brunner.

"It's not my job to take pictures of the crime scene. I'm just doing it with the equipment we got so we don't spend all night in this alley."

The assistant walked around, taking photos, waiting for the sound of the film to be ejected, and then taking the next shot. O'Reilly made him take pictures of the ice behind the lights, although the assistant clearly thought he was crazy.

"Check the photos," he said to McKinnon. If they weren't clear, he wanted a reshoot before Brunner rolled the bodies.

McKinnon nodded.

O'Reilly went back to the door. Someone had deliberately hidden it. And if this wasn't a mugging gone wrong (and, judging by the perfection of those shots, it wasn't), then whoever had stood here had known that these victims or someone like them would come out of that door tonight.

O'Reilly stood and hovered near the brick. If he stood on the east side of the door, whoever came out would see him. But if he went to the west, the door—which opened outward—would hide him.

He could shoot—twice—before the second victim had a chance to turn around.

The shiver came back. He was convinced this crime wasn't random. He was convinced that the killer had been waiting for victims to come out of that door.

Which didn't surprise him. So-called degenerates who frequented famous spots in the city were vulnerable to all kinds of crime. If victims were mugged outside one of the men-only bars in the Village, they wouldn't call it in because they'd have to admit where they'd been.

He suspected this place was the same. If he wanted to mug some well-known men, this was the place to do it.

But to murder them? Was the killer practicing his accuracy or was he actually targeting someone?

"Photos are good enough," McKinnon said.

O'Reilly frowned. That was the other problem with a well-known party scene like this. Good enough became the watch-phrase. No one cared about solving the crime because the crimes were expected.

But O'Reilly didn't care who the victims were. They deserved the best he could give.

"Lemme check," he said and extended his hand. McKinnon carefully handed him each photograph, reminding him not to place one on top of the other. The emulsifier hadn't set yet, and the photos would stick together if they were placed on top of each other.

The photos showed the bodies from different angles, but didn't get a lot of detail. He wasn't sure the Polaroid was capable of the kind of detail he wanted.

At least the pictures would remind him of the scene.

That had to be good enough.

He handed the photos back to the assistant.

"All right then," O'Reilly said to Brunner. "Roll away."

Brunner grabbed an arm and shoulder on the nearest body and pulled it to him. The man's coat was buttoned, hiding the damage from the exit wound, although the ice below was stained black.

He was older—maybe sixty, sixty-five—with a receding hairline. His dark eyes were open. He'd been handsome when he was young; his high cheekbones and well-defined forehead remained. His nose had become bulbous with age and drink but his large chin balanced it.

He wasn't anyone O'Reilly knew.

So much for the celebrity guests at the party upstairs.

"Recognize him?" O'Reilly asked.

The men around him shook their heads.

"Still got his wallet?" O'Reilly asked.

"I didn't even check. I figured it was a mugging," Brunner said, "and forgot once I found that shot."

O'Reilly nodded. "Let's see if he has one now."

Brunner reached into the back pants pocket of the corpse and clearly found nothing. So he grabbed the front of the overcoat and reached inside.

He removed a long, thin wallet—old fashioned, the kind made for the larger bills of forty years before. Hand-tailored, beautifully made—or it had been, before it was covered in blood.

Brunner wiped the wallet on the end of the long overcoat, then handed the wallet to O'Reilly. O'Reilly opened it. And stopped when he saw the badge inside. His mouth went dry.

"We got a feebee," he said, his voice sounding strangled.

"What?" McKinnon asked.

"FBI," Brunner said dryly. Vice rarely had to deal with FBI. Homicide did only on sensational cases. McKinnon had probably never worked with an FBI agent in his life. He didn't know what pains they could be.

O'Reilly hated having them on scene, with their little notebooks and their sly questions. He had no idea what they'd be like with the death of one of their own.

He poked deeper into the wallet. "Not just any feebee either. The Associate Director, Clyde A. Tolson."

The driver's license listed a District of Columbia address. This man wasn't just an important FBI agent, he was here from out of town.

O'Reilly wondered how many people knew Tolson was in New York. And how many more would know he had come here.

McKinnon whistled. "Who's the other guy?"

O'Reilly handled this one. He gave the wallet to McKinnon, then grabbed the shoulder of the other corpse. He pulled it over, his eyes watering at the sudden stench of blood-contaminated perfume. Around him the others gasped, and for a moment, he thought it was because of the overwhelming smell.

Then he blinked the water from his eyes and looked at the corpse's face.

It was familiar. He'd seen it on countless posters, on Time Magazine's cover not too long ago, on the front page of The New York Times damn near every week.

Corpuscular and jowly with the rheumy eyes of a man heading into old age. Hair slicked back and clearly darkened with some kind of gel. He didn't look formidable anymore.

He looked old.

"Son of bitch," Brunner said. "It's J. Edgar Hoover."

"Hoover?" McKinnon asked. He sounded scared. "The Director of the FBI? That guy?"

O'Reilly nodded. He peered down at the familiar face. So much for the quiet swing shift. So much for anonymous crimes.

This was the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, one of the most powerful men in the entire world. Killed by a single bullet—a well-placed bullet—in a back alley in New York three months after the President of the United States, the leader of the Free World, had been assassinated in Dallas.

This case wasn't just political. It was as political as a case could be.

In a few hours, this case would be the focus of an entire nation. Maybe the entire world.

And O'Reilly would be at the center of it all.