Quincy J. Allen, a cross-genre author, has been published in multiple anthologies, magazines, and one omnibus. His first novel Chemical Burn was a finalist in the RMFW Colorado Gold Contest. He made his first pro-sale in 2014 with the story "Jimmy Krinklepot and the White Rebs of Hayberry," included in WordFire's A Fantastic Holiday Season: The Gift of Stories. He's written for the Internet show RadioSteam, and his first short story collection Out Through the Attic, came out in 2014 from 7DS Books.

He works as a Warehouse and Booth Manager by day, does book design and eBook conversions by night, and lives in a cozy house in Colorado that he considers his very own sanctuary—think Bat Cave, but with fewer flying mammals and more sunlight.

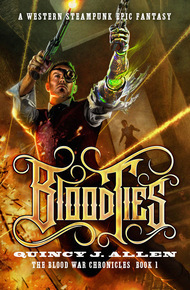

Clockwork Gunslingers • Chinese Tongs • An Epic Quest

THE BLOOD WAR CHRONICLES

When assassins jump half-clockwork gunslinger Jake Lasater, he knows the Chinese Tong wants to finally settle an old score. Unfortunately, Jake has no idea the Tong is just the first milepost on the road toward a destiny he refuses to believe in.

With his riding partner Cole McJunkins in tow and his ward Skeeter secretly hidden away, Jake squares off against a deadly clockwork mercenary from his past and a troop of crazed European soldiers who want him dead. Add an insane Emperor with knowledge of Jake's past and a mysterious noblewoman who desperately needs his help—and Jake is faced with a whole mess of trouble, with no end in sight.

Blood Ties launches an epic saga that spans worlds and threatens the human race itself.

Quincy Allen's Blood Ties starts off the Blood War Chronicles, featuring Jake Lasater, half clockwork, half human, and all gunslinger. This is a fun romp through an alternate America that recasts our own in interesting ways. I'm always a sucker for a Western setting, and I enjoyed this one. – Cat Rambo

"Blood Ties is an old-fashioned carnival ride in the best sense. A cross-genre steampunk shoot'em up full of vivid characters and a well-thought out world."

– Aaron Michael RitcheyChapter One

The Taste of Black Powder

"The Jake I knew was born of thunder, blood, and lies. It made him a better man, but at such a terrible price. And the villain who set it all in motion didn't realize what he'd done until it was far too late."

~ Lady Corina Dănești

Confederate irregulars—gutsy, pissed off farmers, really—had sniped at the camp for three days. Scouts reported some of the Rebs with repeaters, unusual for hog and cotton farmers. Under such circumstances, Union colonels normally did nothing more than post more guards and wait out the sniping. It was practically policy.

This time, however, as Captain Jake Lasater scraped stubble off his jaw with cold water and a dull straight-razor, Major Wilkes—a pudgy, brown-nosing weasel new to the regiment—stepped into Jake's tent without even the courtesy of clearing his throat before throwing back the flap.

"Captain Lasater!" Wilkes barked in a nose-pinched, New England accent.

Jake turned his eyes from the mirror hanging on his tent pole, his hands frozen in place with the blade angled across his jaw and a fresh nick leaking crimson down the razor's edge.

"Colonel Forsythe orders you to take your company along Rabbit Creek and up Jackinaw Ridge to engage Confederate irregulars we believe are encamped there. You are to attack immediately after breakfast!" Without another word, Wilkes disappeared through the tent flap. Not once had the little bastard looked Jake in the eyes.

It was a bullshit order.

Jake knew it. The weasel probably knew it. And Colonel Forsythe sure as hell knew it. Jake knew exactly why the order had been given, which made it that much worse.

Rich-man politics.

Over the years he'd seen far too many good men thrown into meat-grinders for no other reason than the whims of cowardly bastards with too much money, not enough brains, or an axe to grind.

Jake finished shaving, put on his uniform, and strode through camp up to the Colonel's tent, dead set on convincing Colonel Forsythe to either call off the attack or send more than just Jake's cavalry company.

Jake threw a salute barely deserving of the term to the guards, brushed the tent flap aside, and stepped in like he owned the place. He stood before Forsythe with his arms crossed and his feet set wide. The tent flap slithered closed with a hissing of worn canvas. Seconds ticked by as Forsythe continued writing the letter in front of him, the quill in his hand skittering across the paper.

Jake's heavy Missouri drawl carried piss and vinegar as he barked, "Colonel, the next time you want to give me a shit job, at least have the gumption to do it yourself. Don't send some Podunk, boot-licking major to do it for you."

The two men, old friends in the extreme, had gone round and round on orders plenty of times. Forsythe was the sort of man who wouldn't tolerate back talk from anyone under his command. But Jake was practically family. Forsythe and Jake's father had fought together in the Mexican-American war. Upon their return, Forsythe fed the little scoundrel and even changed Jake's diapers on more than one occasion. It was, in fact, a much younger Forsythe who had given Jake the nickname "Trouble."

The Colonel slowly raised his eyes from the tan parchment before him and gave Jake a blank, expectant stare. So began the dance. His Union blue jacket and hat were draped over the chair, but his pressed, white shirt was buttoned to the collar. He slowly laid the white plumed quill down upon the desk and took a pull from the cherry wood pipe angled out the corner of his mouth. As the silence drew out, Forsythe raised an expectant eyebrow. They were both masters of brinksmanship, and they'd done the dance more times than either of them would ever admit.

Jake got the message.

He stood straight and put up a salute considerably better than the one he gave the guards.

"Is something on your mind, Captain?" Forsythe asked in a Missouri drawl identical to Jake's.

"This whole thing stinks!" Jake blurted. He knew he was pushing his luck, but the salute and the question made it legal. Jake was a good card player and knew that if he pushed just hard enough he could get a straight story out of the Colonel and maybe get the decision he wanted.

Forsythe leaned back in his chair and placed his hands on the desk, deliberately forcing Jake to keep his arm up. The middle finger of the Colonel's right hand tapped out one second after another.

Forsythe finally returned a slow, mechanical salute, allowing Jake to lower his arm.

Forsythe's kept his tone level, but Jake couldn't miss the iron in it. "Why, Captain Lasater, I believe you'd like to discuss the order to take Jackinaw Ridge. Am I correct in my assessment of your intentions?"

"Hell, yes!" Jake nearly shouted. "Everyone in the regiment knows that one of those soldiers killed is the son of that pig-butchering war profiteer Cromwell."

Forsythe didn't hesitate. "Why, that's true, Captain. Mr. Cromwell did lose his son in a recent attack. Mr. Cromwell is also the man supplying both the grain and pork for the entire regiment. It's commendable that you keep apprised of current affairs. Are you also aware that our supply lines were cut by Confederate assault units three weeks ago?"

"Of course I am," Jake conceded. "I lost seven of my own men in that attack."

"I am pleased to know that you take such serious responsibility when it comes to keeping count of the soldiers under your command. What you have obviously failed to realize is this places me in the less-than-envious position of still keeping you and the rest of my regiment fed." Forsythe set his elbows firmly on the arms of his chair, laced his fingers together, and stared at Jake over the notch they made like they were the sights of a Winchester rifle.

Jake got a bad feeling—he wasn't going to win this one. Not ready to give up and unable to keep the surly out of his voice, he said, "Isn't it a little convenient that Cromwell showed up only five hours after the attack, offering to step in and supply the regiment … at a substantial markup, I might add."

Deep down he suspected Cromwell had a hand in aiding the mechanized units that cut their supply lines. It wouldn't surprise him if Cromwell had a Rebel heart. Half the regiment believed it. Unfortunately, there wasn't any proof, but Jake would be damned if he didn't at least hint at the allegation.

"Some would call Cromwell's situation fortuitous, and with the correspondence he received from his brother-in-law Senator Willey, giving him considerable leeway in his pricing, there's little I can do to alter the circumstances." Forsythe paused and took a long pull on his pipe. He blew the smoke out with a huff. "Now, knowing camp gossip as I do, you are probably also aware that Mr. Cromwell discussed the matter of his son with me last night. He requested that we immediately attend to the Confederate irregulars."

Jake knew in that moment Colonel Forsythe wasn't going to budge. "But—" he started.

Forsythe cut him off with a raised finger. "What will you be having for breakfast, Captain?"

The question took Jake off-guard. "Bacon and grits, same as yesterday … and the day before that."

"And where did they come from?" Forsythe asked slowly.

Jake hesitated before answering. "Cromwell." He felt like a zeppelin going down in flames.

"Precisely." Forsythe leaned forward and bored into Jake with narrowed eyes. "Captain Lasater, are you the most competent cavalry officer in this regiment?"

They both knew the answer.

"Yes, Colonel." Jake's tone held defeat not pride.

"Do I need to ensure that Mr. Cromwell remains content with our supply arrangement? Thus ensuring that you and my regiment continue to eat something for breakfast?"

"Yes, sir."

"Do I have any choice but to send a small force up that hill?" They both knew of Forsythe's obligation to go through the chain of command before moving more than a single company, which would take days Cromwell clearly hadn't offered.

"No, sir."

"Then buck up, Captain." Forsythe's tone was hardened steel. He took a long pull on his cherry wood pipe and gave Jake a steely glare. "I've read the reports, and Intelligence puts between forty and seventy irregulars up there, and they aren't even dug in. You can beat a bunch of pig farmers, can't you?"

"Those reports are three days old … sir. That's a hell of a long time for that ridge to get turned into a hornet's nest."

"And if it did, Captain Lasater, then I mean for you to burn it down. You have your orders. Dis-MISSED!" Forsythe slowly picked up his quill and returned his eyes to the parchment. The dance was over, and all Jake had were broken toes to show for it.

He wanted to argue but he knew he couldn't go any further, and he wasn't prepared to get busted down to a private—or worse. He saluted in proper, albeit somewhat exaggerated, military fashion, which Forsythe returned with eyes down and his quill again doing its dance across the parchment.

Jake turned on his heel and marched up to the tent flap.

"Jake?" Forsythe said with a hint of gentleness.

Jake paused before the worn canvas and waited.

"You know I don't have a choice, right?" Forsythe asked. It wasn't Colonel Forsythe speaking now. The question came from the man who had changed Jake's diapers, cleaned oatmeal off his chin, and helped raise the boy into the man that stood before him now.

Jake heard it. Hell, he even felt it. He didn't like it, but he had to admit it, and it left a sour taste in his mouth.

"Yes, sir," he said quietly. Without another word, Jake pushed through the flap and made his way slowly through the tents, campfires, and men that surrounded the colonel's tent. He suddenly wished he was back home and that the war had never started. For a fleeting moment he considered jumping on his horse, just heading out and disappearing into a western sunset, leaving the horror—and politicking—of the war behind him. He shook his head, wishing he didn't take his sense of duty and honor so seriously. If he cut and run he'd never be able to look at his father's grave without feeling ashamed. And, truth be told, he didn't want to let Forsythe down. The colonel was as close to a father as Jake had left.

He briefed his company with the bad news, and they all wordlessly ate a breakfast of grits and bacon. Every soldier in the company knew the score, and none of them wanted to talk about it. They also resented each spoonful of Cromwell's grits, every mouthful of bacon, but hunger is hunger and a man can't live off pride.

As Jake looked at his men, he realized the whole camp seemed more quiet than usual. The lull was broken only by a murder of crows gathered high above in the full branches of an oak. The crows chattered and chuckled amongst themselves. Their presence filled Jake with an uneasy feeling. He'd learned as a boy that crows were an omen of power and change, and he'd come to trust them. Unfortunately, they never made it clear whether the change was good or bad. The only change Jake could see ahead was probably a lot of good men killed. His guts churned with anger and frustration. He'd left Forsythe's tent with only the suspicion that he was in for a rough ride, but with the presence of the crows, he no longer had any doubt.

Jake stood, cast a forlorn glance at the murder above him, and nodded to his men. Then, like the soldiers they were, they mounted up and raced along Rabbit Creek as if the devil rode behind them. Jake hoped that a fast pace would keep the rebel emplacement from getting any warning. He cast fleeting glances at the company spread out around him in the forest and wondered how many of them would be dead soon. Politics, he cursed as he spurred his horse to an even faster pace.

The company cleared the trees at the base of Jackinaw only to discover a smokescreen between them and the top of the ridge. So much for hope. He had no doubt that scouts had been able to notify the rebels somehow, and it occurred to him that they probably had one of those new, wireless talkie rigs he'd heard about. If they did, then there was a hell of a lot more than just a bunch of irregulars dug in atop that hill. He didn't have time to do more than give it a passing thought, so he swallowed his fear. He was under direct orders from his commanding officer, and the Union hanged traitors and cowards alike.

Jake was neither.

He pulled his weathered ball and cap pistol and nodded to the man beside him. Clark, his bugler, caught the motion and pulled a gleaming loop of brass off the horn of his saddle. A clear peal rang out, and as one the entire company pulled their pistols and spurred their horses to a breakneck pace. Jake's company was a thundering wall of Union blue spread out to his left and right as they raced up the hill.

The acrid smell of smoke filled his nostrils. The world went hazy gray, with swirls arcing around his horse's head like water around a keel. They were only in the smokescreen for a few seconds, but those blind moments felt like an eternity. A single bullet screamed over his head, probably fired prematurely by a nervous recruit or hapless farmer. He looked quickly left and right, satisfied that each rider he could see through the smoke had nestled in behind his horse's head. The smoke thinned before him like the parting of a gray curtain.

As Jake looked up the hill, his heart sank. He knew in an instant that his entire company was doomed. The dark muzzles of a half-dozen cannons poked out from a sparse tree line, spread out in a wide fan, and each of them pointed down the hill at Jake and his men. In a clearing behind the cannons stood a gleaming Confederate assault unit, its hull a blazing pillar in the morning sunlight.

At fifteen feet tall, the machine towered over the troops ranged around it. The driver stood safely encased within a heavily armored cylinder that jutted up from a long chassis. Its power plant grumbled in an even more heavily armored compartment that bulged out behind the cockpit. The thing roughly resembled a man, but without a head to speak of, and its three squatty legs were designed to easily traverse uneven terrain and keep the heavy machine upright. Assault units were equipped with two thick, heavily jointed arms that could swing and twist in virtually any direction. Rather than hands, they had wide, vicious claws that Jake had seen cut through boilerplate. A large-bore anti-personnel cannon adorned its left forearm and could fire about twenty pounds of buckshot with each volley. The right arm supported a chain-driven Gatling gun. Jake had seen such assault units wreak havoc with infantry and cavalry alike.

Its arms rose, spreading wide as if to welcome Jake and his company like the God Almighty.

In the few seconds he had, all Jake could do was watch.

With a staggering BOOM! the assault unit opened up on the right flank with a blast from its anti-personnel cannon. Men and horses screamed. With a sharp staccato of repeating gunfire, the Gatling chewed into the left flank. A burst of white-gray smoke blossomed from the muzzles of all six cannons, and a deafening, multi-rifle report washed down the hillside. Jake felt the concussion hit his chest. He heard the whistle of incoming shells and the popping of rifles like kernels on a griddle. He closed his eyes, but he didn't have long to wait.

The earth erupted around him. His mouth filled with the taste of black powder as his whole world turned upside down.

O O O

Jake couldn't hear himself screaming.

He knew he was screaming. He felt his chest heaving, felt the rasp in his throat as he cried out in blinding anguish. The bloody, charred stump of his left arm flailed, and little remained of his legs below the thighs other than burned fabric, shreds of flesh, and the white glisten of exposed, shattered bone. Raw, seething horror tore at him, heart and soul. He felt his gorge rising in his throat and spilled what little he'd eaten upon green, dew-covered grass.

The sound of his screaming and heaving never made it past the cacophonous hiss that filled his ears. That one sound filled his world, wrapped itself around him like a soothing balm, and he was grateful for it.

The strange thing about battlefield trauma is that the mind plays tricks on a man. It does its level best to take him out of the moment, distract him from the reality of charred, bloody stumps, shattered bones, and an agony so intense it makes him vomit. That's how Captain Jake Lasater found himself pondering whether history would care that a pig-butchering war profiteer named Cromwell had ended his life at the battle of Jackinaw Ridge.