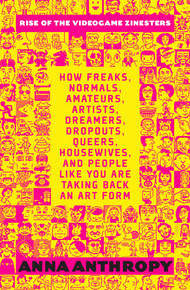

Anna Anthropy is a game creator, historian, and thirty-year-old teen witch. Her previous books include Rise of the Videogame Zinesters and Star Wench, which she recently made a ZZT version of. She lives in Oakland, California with her familiar, a little black cat named Encyclopedia Frown.

Rise of the Videogame Zinesters is a manifesto, a history, a D.I.Y. guide. How did videogames become so homogenous? How are non-professionals and non-programmers transforming videogames with personal creations? And how can you get involved?? Rise of the videogame zinesters is an instruction manual for changing videogame culture.

Rise of the Videogame Zinesters shows us why digital games have the potential to impact our culture in new, surprising, and vital ways, and how people like us—including and especially non-programmers, activists, and everyone outside the cultural mainstream—can take the leap from player to creator and join the coming aesthetic revolution.

"Anna gives the world of video games a crucial perspective from her seat of authority within outsider culture, and illustrates how essential it is for the space to empower voices of all kinds if it is to evolve."

–Leigh Alexander, editor-at-large of Gamasutra"These days, everybody can make and distribute a photograph, or a video, or a book. Rise of the Videogame Zinesters shows you that everyone can make a videogame, too. But why should they? For Anna Anthropy, it's not for fame or for profit, but for the strange, aimless beauty of personal creativity."

–Ian Bogost, director of the Graduate Program in Digital Media, Georgia Institute of Technology"Rise of the Videogame Zinesters is a great guidebook to understanding—and more importantly, participating in—this dynamically evolving culture."

–Jim Munroe, co-founder of the Hand Eye Society and the Difference Engine Initiative"Here, Anna Anthropy demonstrates how people from every background and walk of life are breaking free of the commercial cowardice of major publishers, and bringing their individual visions of the game to life … If game design is to be an art, as those of us who love games fervently hope, it must be rescued from its crushing commercial pressures. You can be a part of its future."

–Greg Costikyan, author of I Have No Mouth and I Must Design"Equal parts autobiography, ethnography, and how-to manual, this book concisely makes the case for the unique power of 'zinester' games."

–Adam Parrish, NYU's Interactive Telecommunication Program (Tisch School of the Arts), and author of the ZZT game Winter"Anna Anthropy is a key personality in the ongoing paradigm shift that is slowly changing the way videogames are understood, by creators and players, and by the wider culture."

–Patrick Alexander, Eegra.comSo, for the first time in the history of the videogame form, people who aren't programmers or corporations can easily make and distribute games. But why would they want to? Why make a game—especially when there already exist the means to write stories, play songs, film yourself for YouTube? What can we do with games that we can't do with those forms?

To begin, let's define what a game is.

You've played games and you have assumptions about what they are. Maybe when you read game you imagine a videogame; maybe when you imagine a videogame you imagine a big-budget run-jump-shoot game. Maybe you imagine Tetris. Since I'm more interested in games, digital and otherwise, that don't resemble games that already exist, I think a fresh definition is in order. I also think it's worthwhile to have a definition that isn't specific to digital games, because I'm interested in the commonalities between digital and non-digital games, and in connecting videogames to that much older tradition.

So here's my definition:

A game is an experience created by rules.

That's pretty broad, huh? I'm interested in as inclusive a definition as possible, though you might argue that mine is too broad: for example, you can use it to describe getting stuck in a traffic jam or paying your taxes. A tax form is nothing but a series of rules you follow to produce a final number, after all. But is it useful to think about your taxes as a game?33Not really. Do the rules on a tax form really create a strong experience, or are they just a method for producing a number?

A game is an experience, and that experience has a certain character. Maybe a game is a story, or maybe it's the experience of control giving way to panic giving way to relief. Maybe it's about taking something and making it grow bigger and bigger and bigger, or maybe it's about two rivals, equally matched, each trying to out-guess the other's plans. The experience that we identify as a game has character, and we can talk about what that experience is.

And if we're discussing an experience, then that implies someone is there to have that experience, someone we refer to as a player. We can't talk about a game without talking about the experience of the player playing that game, even if the playing experience we're talking about is often our own.

The experience we call a game is created by the interaction between different rules, but the rules themselves aren't the game, the interaction is! A game can't exist without a player or players: someone needs to be engaging with the rules for the experience to happen.

How does that work? Consider a game of Tag. Rules: One player is IT, and must tag as many of the other players as possible with a touch. Each of those other players is SAFE when she touches this gnarled-up oak tree. You can see the way the interaction between those two rules creates an interesting (and volatile) dynamic. The players who aren't IT want to reach the tree, but the player who is IT wants to stop them.

You can imagine a situation where the IT player is standing between two other players—one to her left, one to her right— and the SAFEty of the tree. Maybe one of them will make a break for the tree, maybe IT will be forced to pick one of the two to chase while the other gets to make a run at the tree, maybe a fourth player will take advantage of IT's distraction to make a run at the tree from behind. When we talk about a game of Tag, we're talking about this experience. But this situation (and it's a good, tense one) isn't explicitly defined anywhere in the rules. However, notice how these rules guide the creation of that situation. The rules set the players in opposition to each other, give most of the players a goal, and give the other player a reason to intervene, creating a tense dynamic.

What if we were to take either of these rules away: the SAFE location or the player who's IT? Without a SAFE location, players have no reason to stay nearby and interact with the other players, especially the IT player. The ideal strategy to avoid IT would be to go as far away as possible, and that breaks the tension and hence the experience of the game. What if there was no IT player? Then it'd just be people running around, and while a bunch of people running around has value, it doesn't have the character or dynamic of a game.

But there's certainly room to change the details of the rules. Tag, being a folk game, has been played by many people in many places with many, many different versions of the rules. In one version, a player might be done once she's tagged the SAFE tree. As more and more players tag the tree and leave the game, the players who are less fast become greater and greater targets because the IT player can focus less on monitoring the tree and more on pursuing them.

Alternately, what if a player who touches the tree isn't permanently safe—what if players are only allowed to be in contact with the tree for five minutes at a time? That keeps players vulnerable to IT and keeps the game from stagnating. Maybe a player who leaves the tree has temporary immunity to allow her to get safely out of IT's sight, or maybe it becomes a stand-off, where the escaping player has to wait for another player to distract IT's attention before she can make a break for it.

What about freeze tag? In this case, a player who's tagged by IT is "frozen" and has to wait for another player to come and "rescue" her before she can move again. This variation has much more direct interaction between the non-IT players. Instead of just depending on one another as decoys, they have to actively put themselves at risk to aid other players, which only adds to the tension of the game. And it creates a new dynamic between the non-IT players: I rescued you this time, but if I get tagged you're going to have to leave the tree and rescue me.

And that's what games are good at: exploring dynamics, relationships, and systems.