Nancy Jane Moore is the author of the fantasy novel For the Good of the Realm, the science fiction novel The Weave, and the novella Changeling, all from Aqueduct Press. Her short fiction has appeared in a number of anthologies and magazines and in her collection from PS Publishing, Conscientious Inconsistencies. She holds a fourth degree black belt in Aikido.

In other lifetimes she organized co-ops, practiced law, and worked as a legal editor. A native Anglo Texan, she lived in Washington, DC, for many years and now lives with her sweetheart in Oakland, California. Over the last few years, she has developed good relationships with her neighborhood crows. She is currently working on a sequel to For the Good of the Realm.

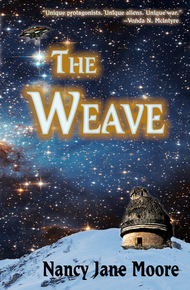

The Weave brings us a first-contact story in which humans, seeking to exploit the much-needed resources of a system inhabited by creatures they assume are "primitive" and defenseless, discover their mistake the hard way. Human Caty Sanjuro, a seasoned marine and dedicated xenologist, and native Sundown, a determined astronomer, struggle to establish communication across the many barriers that divide their species, at first because they share a passionate interest in alien species, but finally because they know that only they can bridge the differences across species threatening catastrophe for both sides.

Solid science fiction that blends adventure, greedy corporations, government cospiracies — all in space.The Weave takes the idea of the first contact novel and moves it into present day science fiction in a story that grabs and won't let go. – Cat Rambo

"Unique protagonists. Unique aliens. Unique war. Nancy Jane Moore's remarkable first novel drew me in and kept me reading and left me, at the end, knowing that Caty Sanjuro and Sundown the Cibolan continue their work and their lives and their friendship. My favorite kind of novel."

– Vonda N. McIntyre, author of Dreamsnake and The Moon and the Sun"In this accomplished first novel, Nancy Jane Moore dramatizes at least three great speculative themes: first contact, telepathic communication, and earthlings and aliens at war. In so doing, Moore narrates the compelling struggle of a brave human xenologist, Caty Sanjuro, to wring interspecies harmony from the chaos of interspecies misunderstanding and mistrust. Like Ursula Le Guin, Moore never settles for pat or clichéd extrapolations. Further, she treats each of her archetypal themes with adult thought-experiment thoroughness and all her characters, human and alien, with insight, respect, and compassion. Aficionados of real science fiction will love and celebrate this remarkable debut."

– Michael Bishop, author of A Funeral for the Eyes of Fire"Moore realistically and enjoyably describes the excitement of scientific exploration, corporate greed, conspiracy, telepathic conflict, and the desperation of natives determined to defend their home against invasion."

– Publishers Weekly"In The Weave, even the sense of wonder gives way to outright surprise: comic, tragic, or somewhere indefinably between. Much as Caty and Sundown strive to know The Other, they come from worlds so different they'll need to recognize – and discard –their most fundamental assumptions about existence, before they can begin to understand."

– Faren Miller, LocusPrologue

I

A small girl — maybe five years old — walks along a pedestrian lane in Demeter, the main city on the asteroid Ceres. Her left hand is firmly attached to her father; her right trails along the handrail, and she wears gravity boots. She is not native to Ceres and will not be there long, so she needs the boots most of the time to counteract the muscle decay that comes from living on a low-gravity asteroid. She doesn't argue about the boots, although they are clumsy and ugly and she much prefers the sensation of floating around you can get without them: her daddy told her to wear them, and she is a well-behaved child.

The father who walks beside her is not a tall man, but he has wide shoulders and powerful legs. His hand dwarfs his daughter's, but he holds hers gently. His skin is light brown, as is his daughter's, though her face shows more traces of Asian heritage than his. He, too, wears gravity boots, but they look less clunky on his feet and go better with his Marine uniform than they do with his daughter's shorts and t-shirt.

As they walk down the street — it's their first visit into the city since they arrived at the military base two days ago — several Ceresians come floating by. They use the handrails to pull themselves along.

They are young people, their hair cut and dyed in the furthest extremes of this year's fashions, their bodies showing implants chosen with care to shock their elders, their legs dangling. Their feet are bare, the toes curled under.

"Look, Daddy," the little girl says, staring in fascination. "Aliens."

Her daddy laughs. "No, honey," he says. "They are people, just like us. They just aren't wearing their boots right now." She isn't old enough to be told the whole story: that these people have adapted to the low gravity and their muscles have atrophied. In some ways, the father muses, they are becoming a new species. But that's too complex for a five-year-old, who means "non-human intelligent life forms" when she says aliens, even if she doesn't know it yet.

The child is disappointed. She very much wanted to see aliens. She tells her father — in that deadly serious tone young children use when they've figured out something important and need to educate their parents — "Someday I'm going to meet aliens."

And her father — to his credit — does not say, "There's no such thing as aliens." He says, "You bet you will, Caty. You bet you will."

II

On the fourth planet from a bright yellow star, someone sits staring at a small pane of ground glass, watching the night sky. Stars and planets abound: the night is clear, as it often is on this planet.

The pattern is a bit blurred. The being holds the piece of glass firmly with two hands, reaches down with a third hand, and up with a fourth, adjusting two knobs. The focus improves; the image is clear.

The being recognizes the patterns cast by the stars and planets, for it has watched this sky many times, knows the different ways it looks at the different times of the year. In one corner of the sky, it sees something that moves, something that does not belong. It watches the object for a while, notes its path and trajectory, and then sits quietly, eyes closed, in deep concentration, reaching out to others in the weave.

As the being sits, a younger one comes into the room and climbs into its lap. This one looks like the telescope watcher in miniature: both are covered in fur that evokes the pale gold of dawn or sunset. The first one does not open its eyes as the newcomer wiggles around to make itself comfortable, though it strokes the small one as a parent strokes a child.

The small one leans over the ground glass. The object that does not belong is still there, moving across the sky. From the child's mind come images of fantastic beings: wide fat things, with no arms or legs; horned creatures twice as tall as any creature ever seen.

The father is amused by these images. It strokes the child again, untangling a knot in its fur. But it can feel nothing from the sky object, and neither can the others with whom it is connected. Nothing with a mind. Nothing alive.

A debate — of sorts — begins to rage within the weave. An image of some kind of beings — like them but not like them — sending the object. Another one of rocks and matter, nothing tied to life. A protest that this object seems different from the meteors and bits of asteroid that they know. And from the small one — insistently — constant images of unusual beings, each one more improbable than the last. The debate continues without resolution.

A last image is introduced, one out of ancient history: many objects similar to the one in the night sky and beings landing, creatures that look neither like them nor like anything in the child's imagination.

The child can feel the adults' fear, but is more excited than afraid. Other worlds exist beyond this place; other beings populate the universe. Then and there it resolves to meet these others one day.

The father is engrossed in the discussion of what should be done, but spares a moment for the child's thoughts. And pats the small one gently, encouragingly, as if to say, yes, my dear one, yes, you will.