Stephen Knight was born in Hainault, Essex in 1951. He left school at sixteen to pursue a career as a journalist. He was a reporter on several weekly London papers and by age 20 had become chief reporter of one of them. In 1973, Knight met a man who claimed to know the truth behind the Jack the Ripper murders. Knight investigated the case, obtaining access to previously closed files of the Home Office and Scotland Yard. This led to his first book, the bestselling nonfiction work Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution. His first and only novel, Requiem at Rogano, appeared in 1979 to generally positive reviews, and a further nonfiction work, The Brotherhood, purporting to expose the secrets of the Freemasons, appeared in 1984.

In 1977, Knight began to suffer from epileptic seizures, and in 1980 he agreed to take part in a BBC documentary on epilepsy after seeing an advertisement in the newspaper. As part of the television program, a brain scan was taken, which revealed a brain tumor. Though surgeons removed the tumor, it recurred four years later, and Knight died in 1985 at age 33.

London, 1902. A string of murders committed by a killer the press has dubbed the Deptford Strangler has the police mystified. The victims seem to have nothing in common, and the crimes appear random and motiveless. Meanwhile, retired Inspector Brough and his nephew Nicholas Calvin, researching a book on the history of murder, unearth a series of killings committed in Rogano, Italy in 1454 identical in pattern to the present-day crimes. What possible connection could there be between these horrific events separated by over 450 years? Brough and Calvin are determined to find out—but they are not prepared for the terrible truth they will uncover.

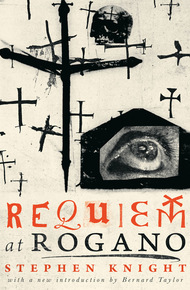

Originally published in 1979, Requiem at Rogano was the only novel by Stephen Knight (1951-1985), best known for a nonfiction bestseller that promised the 'final solution' in the case of Jack the Ripper. This new edition of Knight's novel, a page-turning supernatural thriller whose plot twists will keep readers enthralled, features an introduction by Bernard Taylor.

A historical, literate, and endlessly clever noir that shows the potential of the genre—any type of book can be noir, even historical crime. What if Umberto Eco wrote for scripts for Hollywood B-movies? A must! – Nick Mamatas

"A superlative thriller . . . I have not had such a good weekend with a thriller for years . . . I recommend this to all who enjoy literate crime fiction."

– Martin Seymour-Smith, Financial Times"A confident debut."

– The Guardian"Ingenious."

– The ObserverRetirement, thought ex-inspector Brough, is all very well if your heart is in it. He settled himself into his favorite fireside chair and looked out at the mist creeping slowly up from the Thames. The cabs rattling along Jermyn Street already looked indistinct and spectral in the December dusk.

An early edition of the Star lay open on his lap. "Fourth Man Strangled by Mystery Assassin" declared a headline at the top of the page.

Brough reached for his pipe and began to fill it.

"A university professor done to death in Camden Passage, the Yard running around in circles not knowing who to arrest next, and me sitting here sinking into my dotage," he muttered. "It just doesn't make sense."

Brough had been melancholy and shiftless for more than a month, ever since the strangler's first appearance at Deptford had sent the press into hysterics and the Yard into confusion.

My brain is as sharp as it ever was, he thought. But the great god Regulations is not concerned with brains.

Daily physical jerks and a few Sufi exercises learned during his army days in India kept his body as sound as his mind. He was as fit now as when he had taken over the metropolitan murder division of the CID back in '91.

But Regulations said an officer must retire at sixty, and no one—not even the commissioner—could defy Regulations. When, on the threshold of retirement, its depressing reality had at last become plain to him, he had tried hard to bend a few rules. But it was hopeless. He might just as well have sought the Holy Grail in the men's locker room. On his sixtieth birthday, not a day sooner or later, the ax had fallen.

Oh, he had tried to make the best of it. He had tried to tell himself that detective work was just another way of saying donkey work. And, to a point, that was true. Every startling solution that hit the headlines, every dramatic arrest, was the product of weeks or months of often tedious legwork.

Donkey work, legwork, bloody hard work.

But it was hopeless. All those arguments appealed to the mind. They didn't really touch him.

How could they? Reginald Arthur Brough had never troubled about hard work. He had savored every moment of it. In twenty- six years with the uniformed branch and eleven with the Detective Department he had earned the reputation of being one of the most single-minded men at the Yard. And donkey work or not, no man on the force had relished his duty more than Brough.

Never one to be defeated easily by misfortune, he had striven valiantly to fill the empty weeks and months of his retirement.

But that hadn't worked either. In eighteen months he had accomplished much of what he had imagined would take years. Since leaving the Yard in June of the previous year he had read the complete works of Mr. Dickens—apart from Bleak House, which he couldn't begin to get his teeth into; he had endlessly haunted the Natural History Museum; and he had photographed the scene of almost every notorious murder that had ever taken place in his beloved London. He had trudged from the splendid Kensington mews where Mrs. Cheyney-Loring had met her comeuppance in the shape of Spider Bill (to whom she had been married for twelve years without suspecting his identity) to the very house where the horrible Ratcliffe Highway murders had been committed, and he had taken hundreds of pictures en route. The sepia prints now occupied every inch of space on the walls, and, together with a formidable array of gruesome knick-knacks from a lifetime spent chasing criminals, they turned his gaslit rooms into a veritable museum of murder. He looked around him. Between the books and the murderers' bric-a-brac, strange Buddhist gods peered at him out of the shadows. He dropped his gaze to his hands and ran his eye along the crease that the palmists called the life line. How far have I traveled along it? he pondered. I see its beginning. And its end. And all its tributaries. But whereabouts is now?

God, how he ached to be back on the job. Other men, not yet sixty, nudged him in the ribs and chortled about the freedom of retirement. Well, they could have it. The only freedom he wanted was about the only freedom he couldn't have. Freedom, real freedom—carte blanche—to set up the machinery to snare this bastard strangler.

But what use were dreams? Sitting there alone in the flickering firelight of his rooms, he felt adrift like a dinghy that had broken its moorings. Botany, reading and amateur photography never had and never would replace the thrill of the chase. And learned men getting strangled in dark alleys miles from where they lived aggravated his dissatisfaction with life.

Such incidents made him yearn to wind back the clock and show these youngsters with three stripes on their arms before they were thirty how a criminal investigation should be handled. Dreams again. Empty, useless dreams.

Now with a little woman beside me, he reflected, I wouldn't feel so cut off from life. I wouldn't feel the need to fill my days with so much doing. Just being would be a fine thing.

He yawned. Troubled nights for the past few weeks had added to his misery.

He looked again at the unopened letter lying on the table by a plaster bust of his old sparring partner Charles Peace. It had arrived with the second post, but he had been so involved in developing some photographs that he had had no time to open it. Later, when the prints were hanging up to dry in his makeshift darkroom, he had been too immersed in mourning his lost past to give it a thought. Rising, Brough picked up the letter, walked to the window and opened it.

Grand Hotel de New-York

Palazzo Ricasoli

Florence

29 NOV 1902

R. A. Brough, Esq.

35a Jermyn Street

London W.

My Dear Uncle,

Forgive my using the typewriter, which at best seems cold and impersonal, but in three years of newspaper work my handwriting ability seems to have atrophied.

Journalism is a pretty precarious existence, as you warned me it would be—more so when you sell what you can on the open market rather than buckle down to an eight-to-seven drudgery with a regular employer. There's not a great deal more to be made writing books, as I found with King Teddy, but the odd literary venture does swell the coffers a bit. And perhaps more importantly it helps me keep my hand in with the king's English, which my twopence-a-lining for the dailies rather abuses. As an indignant professor of English told me before I came down from Oxford, any similarity between journalese and the English language is purely coincidental!

I know Teddy wasn't the hottest seller of the year, but it did moderately well and I have enough confidence to think my style will improve with experience, so I've decided to start work on another book.

How does the idea of collaborating with me on a History of Murder appeal to you? I realize I have been rather aloof of late and I must have seemed ungracious in my neglect of our old friendship, but life takes some queer twists and the course of our existence is so often outside our control, as you have told me often. No matter. I shall be lodging with my parents for the foreseeable future when I return home and for my part I should dearly love to revive our old association. And after a year and a half of forced inactivity you must long to get your teeth into something challenging and fulfilling. You might be out for the count as far as new cases are concerned, but who better than a man of your experience to tackle a proper account of the great murders of the past—and to have a crack at clearing up a few of the unsolved ones? Writers with no training in detection are producing books every year with ingenious and widely discussed theories on old mysteries from the identity of the man who wrote Shakespeare's plays to the riddle of the little princes in the Tower. Andrew Lang has made a career out of mystery.

As far as I can discover there has been no well-researched history of murder from the earliest times to the present day, and old Harris at Methuen & Co. thinks there could be a good market for it. Not knowing my plan to ask you to collaborate with me, Harris suggested that a foreword from you would give the book a sort of imprimatur. Imagine how the reading public will sit up and take note if the title page is inscribed "By Former Scotland Yard Inspector Reginald Brough. . . ."

I thought we could start with Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, who was clubbed to death in the Roman senate in 133 B.C., and document every notable murder that's been committed since—reporting facts, commenting, and where possible offering new explanations for stubborn mysteries. I have already done six months' work on a synopsis and I've been digging into some pretty bizarre cases.

I have stumbled on one case the like of which you've never seen. It must beat anything they ever handed you at the Yard. That's really why I am in Italy. If we can get to the bottom of this one it will be the highlight of the book.

I still have a lot to do here but I expect to be back in London by Wednesday, December 10th, at the latest. If I don't contact you before, I shall be at the Beggar's on Thursday the 11th at six if you should care to join me.

With great affection

Your nephew

Nicholas

P.S. I'm not staying at the Hotel de New-York. I just nipped in for a cup of tea and to pinch some stationery.

Nicholas Calvin. My God, it must be nearly two years.

Before Oxford, Nicholas had been Brough's companion through many long evenings. They shared a number of interests, notably the detection of crime, and each enjoyed listening to the other expound on his own subjects. Despite the thirty-odd years that separated them in age, a warm friendship had grown up between them. Nicholas was the only son of Brough's sister Alice, so the old man had known his friend almost since he had drawn his first breath.

There had been a grand reunion when Nicholas came down from university and another a short time later when his biography of the new king was published, but since then nothing. Brough was not so unsympathetic as Nicholas seemed to fear. He had treasured their friendship, but for at least four years before it ran down he had expected his place in his nephew's affections to be replaced, quite properly, by the tenderer charms of a young woman. As far as the old man knew, no serious love had as yet materialized. Doubtless there had been mistresses, but the lady in Nicholas' life had turned out to be his work, and Brough no more resented that than he would have resented a woman.

The letter had taken nearly a fortnight to arrive, and by Nicholas' calculations he would have arrived home last night.

A History of Murder. It was quite a thought.

Of course, Nicholas would have to do the writing. And Brough would insist that his own name came second on the title page—"By Nicholas Calvin and Reginald Brough."

But the unsolved murders of the past exerted a peculiar fascination. . . . As Nicholas said, it would be unique for a respected detective to turn his training to that sort of use. . . . Mr. Dickens and botany could go to the devil, or at least to the old folks' infirmary where they belonged. . . . The work involved would be immense. . . . But it would certainly put the mockers on this mental stagnation, this so-called retirement. Retirement? More like a slow march to death.