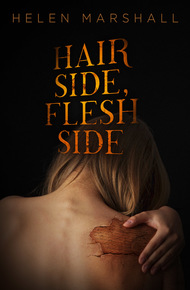

Helen Marshall is a Lecturer of Creative Writing and Publishing at Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge, England. Her first collection of fiction Hair Side, Flesh Side won the Sydney J Bounds Award in 2013, and Gifts for the One Who Comes After, her second collection, won the World Fantasy Award and the Shirley Jackson Award in 2015. She is currently editing The Year's Best Weird Fiction to be released in 2017, and her debut novel Everything that is Born will be published by Random House Canada in 2018.

A child receives the body of Saint Lucia of Syracuse for her seventh birthday. A rebelling angel rewrites the Book of Judgement to protect the woman he loves. A young woman discovers the lost manuscript of Jane Austen written on the inside of her skin. A 747 populated by a dying pantheon makes the extraordinary journey to the beginning of the universe. Lyrical and tender, quirky and cutting, Helen Marshall's exceptional debut collection weaves the fantastic and the horrific alongside the touchingly human in fifteen modern parables about history, memory, and cost of creating art.

I first met Helen when she worked for the excellent Canadian press, ChiZine Publications, and edited my second collection, Chimerascope. I didn't realize how lucky I was at the time. Helen has established herself as a master of the short form, and this, her first collection, is ample proof. Aside from being a finalist for the Aurora Award, Hair Side, Flesh Side also won the Sydney J Bounds Award. – Douglas Smith

"Stories subtle and unsettling: Helen Marshall clothes the uncanny in new flesh and then makes it bleed."

– Kelly Link, author of Get in Trouble"A tour de force of imagination, this remarkable debut collection uses the conventions of dark fantasy and horror as the framework for some of speculative fiction's most unusual stories. VERDICT Fans of experimental fiction and exceptional writing should find a wealth of enjoyment here."

– Library Journal, starred reviewBlessed

It was three weeks to her birthday when the big box came—each of the moving men taking an end, grunting and sweating as they heaved drunkenly to the spot where Chloe used to park her new two-wheeler. She had been told to move it to the backyard where it now leaned up against the fence, exposed to the elements, shining ribbons soggy from last night's rain. But that was okay, because she knew what this was, what it had to be, and she was so tingly with excitement that it didn't matter if the gears of her bike rusted out.

Chloe's parents took her by the hand, her mum on her right, her dad on her left, and they walked into the garage to see. "It's for you, honey," her mum—her other mum—said with her biggest smile, "it's just for you."

"It's from Italy," said her dad. "We brought it all this way to celebrate. We know your birthday's not for another couple of weeks, but, well, sweetheart, we wanted you to have something early—"

"—something from us—" her other mum cut in.

"—before you have to go back home."

And they looked at each other encouragingly and they looked at her encouragingly, but Chloe was hardly listening because she was looking at the box. It was very big—as long as her bed, made of thick wooden slats with HIC JACET SEPVLTVS written in bold red letters.

"Go ahead, sweetheart," said her other mum. "Go on and open it. Henry, tell her to open it."

"It's okay," said her dad. "Here, sweetie, fetch me the crowbar."

And Chloe brought him the large hooked crowbar, and he fit it into the lid of the crate and, after some more grunting and heaving, off it came with a pop. A kind of horsey smell filled the air, a smell like dirt and old things that made Chloe feel all warm and tingly. "Is it—?" she asked, but her dad was lifting her up onto his shoulders.

"Shh, honey, see for yourself."

At first, all she could make out was the layer of straw and the cloud of dust that leapt into the air as her dad began to root around. It glittered in the sunlight streaming through the garage door, but she still couldn't see what was inside the thing, not through the settling dust and her dad's rooting arms, and she had to hold tight around his neck so she didn't fall off. But then, then there was something peeking through, brown and leathery, something that might have been a football, except it wasn't a football because her dad was still clearing. And then Chloe saw it: a face, and more than that, a face with pale, stringy hair tangled up in the straw and a brown, leathery neck and thin, twiggy arms and thinner, twiggier fingers.

Her dad bounced her on his shoulders and then heaved her off again so she landed gently on the ground, and she stood tip-toed until she could see over the top of the crate. Chloe fingered the straw shyly, not daring to touch it yet, not daring to stroke the soft leathery skin.

"For your birthday, kiddo," he said in a warm, excited voice. "You're almost seven, and we wanted you to have this—"

"Lucia of Syracuse," her other mum interrupted. He gave her a look, but it was an affectionate look, one that showed he didn't mind much. "Died 304. A real, genuine martyr."

Chloe's mouth opened in a little "oh" of delight and then she reached out and let her index finger brush against the brown leather cheek. It was rough like a cat's tongue in some places and smooth as fine-grained wood in others, where the bone peeked through. "She was about your age, sweetheart, when they came for her. Wanted her to marry some rich governor who thought she had the most beautiful eyes in the world. But, oh no, she wasn't having any of that. Do you know what she did?"

"She plucked out her eyes," Chloe said, barely a whisper, as her finger traced the smooth curves of the eye sockets.

"That's right," her other mum beamed. "That's exactly right, sweetheart. Now there's a real saint for you, a saint to be proud of. Not just any martyr had that kind of panache."

Her dad nodded sagely, and Chloe nodded too because it was true, this was something, this wasn't one of those knock-off relics that some of the other kids got: there were about five girls in her grade alone who claimed to have Catherine of Siena, and that was nonsense, there was only one Catherine of Siena and they couldn't all have her. Melissa Johnstone admitted she only had a finger bone, and it was a hand-me-down from her older sister's Theresa of Avila anyway—her parents couldn't afford a whole new saint, not for their third kid.

But Chloe could tell just by looking that this was the real Lucia, that this little girl, a little girl her own age, had been good and kind and best beloved of all. And then, there, it happened. Chloe felt a warm rush of heat and all the hairs on her arm stood up. This was it, this was the moment! Out of the crate stepped a little girl the same age as Chloe, with long dark hair and olive skin and a beatific smile.

"You won't be lonely now when you visit, sweetheart," her dad said. "Lucia will be here waiting for you."

And afterward they took Chloe inside and Lucia followed serenely, smiling at her with only the faintest stains of blood on her neck where the Roman had stabbed her, but she didn't seem sad and so Chloe wasn't either. There was birthday cake and it was her favourite—double-chocolate with thick brown icing that seemed to fizz on her tongue—and she was even allowed a second piece. At the end of the night, when she had had as much cake as she could fit inside her, and her eyes were starting to drift shut, they tucked her into bed. They stood, one on either side: her other mum on the right, her dad on the left, and the third, Lucia, a faint ghostly little-girl shape by the window.

"Can she come home with me? Please, dad?" Chloe asked dreamily, but her parents shared a look, a special look, and her dad crouched down beside her.

"I need you to listen, sweetheart." He looked up at her other mum for support in the way he did sometimes. "You can't tell Clare—well, your mother, your mum back home—about this. Okay, sweetie? It's important. This is a special present. And because it's a special present you need to keep it a secret."

Chloe looked at her dad, and his eyes were so sad, so she promised. And when she fell asleep, she dreamed of Lucia, bathed in golden light with her beautiful blank eye sockets, and she forgot the sadness in her father's eyes and she didn't think about what it would be like to go home.

*

In the end, they let her take a finger—only a pinkie—from Lucia's right hand where the sinews were weakest with age; it snapped off like a broken twig. She just had to promise, cross her heart and hope to die, that she would keep it secret. "Your mother—Clare—at home, she wouldn't like it if she knew," her other mum said as they packed her overnight things back into the little pink suitcase she had brought with her. Her other mum was tall and beautiful with soft, soft hair that she sometimes let Chloe brush; her mother back home didn't like it when Chloe talked about her. "Your father said you were good, you'd be careful. And you'll come back, won't you, sweetheart? To see Lucia?"

"She can't see me, Mum," Chloe replied as she folded her pyjamas, "she gave away her eyes."

"Even so," her other mum said, and she kissed Chloe on the forehead.

Lucia went with her, of course, but with only the little boney finger she appeared as the faintest of faint outlines, barely more than a whisper of a shadow. Chloe didn't care though; Lucia filled her with a sense of light and warmth, and no matter how dark it was she never felt the night terrors with Lucia there. She kept the finger in her pocket when she went to school, and she only showed it to Melissa because Melissa had a finger too. "But you're not supposed to have one yet!" Melissa squealed with wide eyes. "It's not your birthday."

"It is too. My parents only see me once a month. It's my special present."

But Melissa only muttered darkly, "You're not supposed to. Now you'll get two because you have two mums, and I'll only have a lousy finger." She wouldn't look at Chloe for the rest of the day, and as Chloe sat in her desk, trying to figure out her multiplication homework, she could see the outline of red standing out darker on Lucia's neck and she knew there would be trouble.

Later that evening, her mother—her mum at home—received a call from Melissa's mum and that was it, she demanded to see the finger. "This was a gift from them, wasn't it? Well. That's just like them. They know you aren't properly seven yet and they're trying to get a present in early." She paced about the kitchen wielding a wooden spoon like Goliath's club. "I won't have any of that. I won't have any second-class finger-bones in my house." Chloe tried to tell her that they didn't mean anything by it and that it was all right, she didn't need a second saint, but her mother rounded on her fiercely. "That's what you think, is it? You don't want mine. Fine. You can make do without any." Then her mum snatched the finger out of her hand and threw it into the garbage disposal; it disappeared in a terribly grinding of gears so loud that Chloe had to cover her ears. The little ghost-girl—just like that!—vanished like a burst soap bubble.

"Oh, I bet you think you're so clever," Chloe overheard through her locked bedroom door that night as she hugged her covers to her chin. The dark seemed so much darker now, like it had all crowded into the room when her mother closed the door. "Saint Lucia—ha! What, because she's got your eyes? She hasn't, you know. They don't look a thing like yours and if they did, well, I'd pluck them out myself and send them to you. You think she likes saints, do you? I'll get her a saint. I'll get her Joan of bloody Arc—there's a saint for you, there's someone who really counted, not one of those timid little virgin saints."

And she did: it might have cost a fortune but her mother—her mum at home—had the Seine dredged for ashes and three weeks later on her birthday, she presented Chloe with a heavy glass pickle jar filled with Parisian mud.

"That'll teach him," she said, grinning sharply at Chloe. "You want to try martyrdom, try burnt at a stake." And they sat side by side, a half-eaten slice of carrot cake between them, the candle licked clean of icing, and her mother glaring at the jar, waiting for something to happen.

By ten thirty it was getting quite late, and Chloe was getting sleepy; it was past her bed time, but her mother gripped her wrist fiercely. "She's there, it just takes longer, she was roasted alive for Chrissake. But she'll come. She'll come, and you and I are going to wait here until she does."

And they did. And ten-thirty became eleven. And eleven became eleven-thirty. And when the last chime sounded for midnight, with a harrumph, her mother pretended not to look when Chloe slipped her arm away and climbed the stairs to her bedroom, closing her door herself, even with all the darkness crammed into the little room.

But in the morning when she wandered downstairs in her pyjamas for breakfast, there was a watery shape sitting at the table with close-cropped, boy-hair and a chainmail shirt.

"Good morning," Chloe said shyly as she took her seat, but the French girl stuck up her nose and refused to make conversation.

"Où sont mes ennemis?" she asked. Her mother made her carry a thermos full of mud to school that day, and all her friends wanted to know was it really Joan of Arc—all of her friends except Melissa, who made it quite clear that they weren't friends at all anymore, not if Chloe had two saints. And Joan didn't speak to Chloe, not even once, and she never smiled.

*

Chloe didn't like Joan very much. Oh, she tried to because here was another girl and she too was best beloved, but, well, Joan was fierce. She smacked Chloe's fingers with the flat of her sword when she reached for a cookie, and whenever Chloe tried to put on a dress, Joan would shake her head and scowl at the hemline; worst yet, on days when she was particularly cross she would set herself afire. Then she would writhe about as her skin went black and crispy. She would look at Chloe accusingly, her eyes burning with righteousness, as the flames consumed her hair like a halo.

Chloe tried to tell her mother—her mum at home—but she would only look on with approval. "That's the way it's supposed to be, isn't it? Real martyrs have standards; real martyrs won't put up with nonsense, no. It's good for you to have a little discipline in your life, really, Chloe. I won't be there all the time." And Chloe supposed she was right. Even so. At night, when the room was dark with shadows and Chloe could feel the night terrors coming on, she still found herself wishing that the fire in Joan's eyes helped just a little bit.

On Friday morning, Chloe packed up her pink suitcase and waited by the door for her dad to pick her up. She had been looking forward to the visit all week: she had been extra good and extra kind, and Joan hadn't had to immolate herself even once since Tuesday. Her mother, though, had taken to pacing in the kitchen: she was always like that the day of a visit, always tense and strange, prone to fits of tears followed by scolding followed by remorseful hugs that were always a bit too tight.

"Come here, Chloe," her mother said, and that thing—whatever it was that only came on visit days—was there in her eyes. She placed a glass of something black and sludgy in front of Chloe. "I want you to drink this, darling, I made it for you special."

"I'm not thirsty, Mum," said Chloe, but even though she didn't want to, she could see the tips of Joan's hair starting to light up like little fuses and so she closed her eyes. She gagged and she coughed and she sputtered, but she managed to drink it all.

"Good," said Chloe's mother, "there's a dear." And she hugged Chloe very tightly.

Then her dad rang the doorbell and Chloe ran to him and flung her arms around his neck. Her mother said nothing, she never did, but Chloe didn't mind because he was picking up her suitcase, and then they were out the door. But in the car, Chloe began to feel quite ill. "Would you like something to drink, sweetheart?" her dad asked, but Chloe said no, she didn't. "Are you hungry? Do you need to pee?" And Chloe still said no, but something strange was happening to her skin, first it started to itch and then it started to prickle with sweat and then it started to burn.

"Dad," she said.

"What's wrong, sweetie? Should I pull over?"

"Dad," she said again, but this time her voice sounded small and frightened and Chloe couldn't recognize it because all she could hear was, "Mon père, mon père."

Chloe spent the weekend in bed with a fever of 105 degrees. Her mum—her other mum—laid washcloths on her forehead but nothing helped, nothing stopped that feeling of fire licking at her skin, of her hair shrivelling up. Sometimes, she would catch sight of Lucia by her window, shaking her head sadly, serene, the blank spaces of her eyes as dark and as cool as a well. And then she could only whisper, "Mon Dieu, aidez-moi, aidez-moi." Then her parents would exchange glances between them and they looked so scared and small beside the bed. Chloe wanted to reach out to touch her other mum's hair, but she was afraid the flames that licked her fingers like birthday candles might devour her all up.

Chloe could hear bits of the phone conversation floating up to her through the floorboards, not even words anymore, but just bits of anger and sadness and fear and fury all tied into one. They couldn't take her home. They were afraid to move her. They didn't know what was wrong. And so on Sunday her mother came, and when Chloe saw her she didn't seem small like her parents. She seemed huge, hulking, massive; her legs were like two Ionic pillars, and her face seemed carved from marble, it was so firmly set. She glared until her other mum fled the room. "What have you done, Henry?" her mother said. And her dad hung his head miserably and he slunk out too. Chloe could feel the fire burning on her skin, searing flesh, blackening bone.

Her mother sat down by the bed where her other mum had kept the washcloths. She touched her daughter's hair the way she did when Chloe had been very young. "I love you," she said. "My little girl, my darling, and I'm sorry this is so hard. But it's not supposed to be easy, is it? Real love isn't ever easy. Sometimes it's hard and sometimes it hurts but if it's real love then you don't ever leave, you don't, no matter how much it hurts. I want you to know that. I'm here with you now, my darling, and I won't ever leave." And her mother stroked her face lightly with fingers that were hard and sharp as broken bones. "This is their house and they want you to pretend that it is yours, they want you to pretend that you are their child, that you belong to them. But you don't, love, you are my daughter. Your hands are my hands and your fingers are my fingers and your eyes, oh my darling girl, your eyes are my eyes."

And she cradled her daughter's head gently in the crook of her arms, and the pain was bad, it was very bad. But she loved her mother very much and she was willing to bear this pain for her mother, she was willing to let the fire devour her if that was what her mother wanted, because that was what love was: it was fire and it was torture and it was being hacked to pieces, and broken fingers and knives and hammers and pitchforks and spears, and it was being drowned and it was being suffocated and it was being locked up in dark, dark places. Chloe knew that, she knew that in the deepest bit of her. And she loved her mother enough to bear the pain, really she did, enough not to ask why or for how long she would suffer, for how long she must bear the weight of her love.

But even so. Even so. Chloe looked up through the halo of fire into her mother's eyes, wet with tears—real tears, because she hated seeing her daughter in pain. She reached up gently, shyly, and she felt the skin cool beneath her fingertips, and then—it was hard because she hated the darkness, and she was afraid, she was truly afraid, but she could see Lucia standing by the window, and Lucia looked so beautiful, calm, patient and kind, everything she had ever thought love was. And so Chloe plucked out the eyes from her skull, just like that, like a soap bubble popping, and it was done.