Zoë Jellicoe is a writer, editor and occasional producer based in Berlin but hailing from several places, most recently Dublin. Working as a journalist since 2010, Zoë has written about popular culture, festivals, fine art and videogames in publications in Brussels and Dublin. She is currently working on a performance art project in Berlin, managing the narrative design for an upcoming indie game and founding a VR collective.

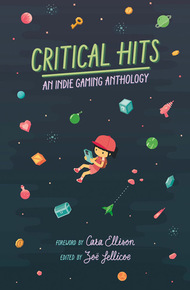

Critical Hits is a collection of original journalism from ten writers and developers in the independent gaming community, including Leo Devlin, Holly Gramazio, Joe Griffin, Owen Harris, Zoë Jellicoe, Dámhín McKeown, Katharine Neil, Emilie Reed, Austin Walker and Aidan Wall, with a foreword by Cara Ellison. Compiled and edited by Zoë Jellicoe, the anthology was created to reflect the diverse range of insightful and unusual voices in online independent gaming journalism and development, exploring everything from spatial design and existential fear, the digitisation of female care, procedural generation and the representation of dating through text-based mechanics.

"Available on eBook for the first time, these essays feature a whole bunch of smart contributors, from Holly Gramazio to Austin Walker & beyond, and some smart and affecting essays on culture & game design in the indie game community." – Simon Carless

"It seems a whole new generation of writers and thinkers have grown up and now want to give videogames the same robust treatment normally reserved for literature, film and art theory … It's about time, and seemingly leading the charge over here is editor Zoë Jellicoe."

– The Thin AirForeword

Cara Ellison

'My son plays videogames,' a mother stops me to tell me at the book festival. Anxiety wracks her face, the face that a Marvel superhero might have if someone was in trouble.

I try to read what she means by 'videogames'. Something is insinuated by the term. But what is it? People who make their living writing down what they think about 'videogames', for example, do not even agree on the term: is it two words, or a compound word? What is a 'video' game? Is it a computer game? Are 'videogames' and 'computer games' two interchangeable terms, or is one a subgenre of the other?

Does she mean big budget console games? Massive multiplayer online games? Does she mean the sort of videogames that newspapers demonise – the Grand Theft Autos, the Dooms, the Carmageddons? Is she going to accuse me, a bumbling and possibly misguided Edinburgh International Book Festival advocate for the 'videogame', of brainwashing her child?

Or does she mean what I mean when I say 'videogames'; a term that conjures up vast universes pocked with stars; islands surrounded by limpid tides; ten friends dotted across a globe controlling avatars with batwings and magic missiles; the sad strain of saving virtual people from disease; graphic neon murder simulators; graceful squirrelesque jumps; Japanese murder mystery Twin Peaks; lurid, idiosyncratic rhythm games; intricate Lego-like city-building simulations; grandly scaled Rube-Goldberg puzzles; wordless, tragic love stories; nest-like choose-your-own-adventure browser poetry; philosophic nihilistic lullabies; succulent gardening; odes to horror movies and pulp; meditations on the performance of movement; dancing engines; masturbation aids with controllers you can fuck; a parade of dragons approaching on a sunset horizon; anime girl visual novels; slapstick comedy-filled hallucinogenic dream-trips? Does she mean symphonies of sound and movement, that try to imitate the rage of living, then die having achieved nothing? Does she mean huddling around a TV screen with friends and racing a virtual car along a virtual road dotted with banana skins, until you all drop to the carpet in laughter?

I think, Is that it? Is that what you mean? Do you mean to say this, my medium, might be filling you with anxiety? Of course it does. It fills me with anxiety. 'Videogames' is so broad a term that I cannot explain it to anyone – least of all to myself. I feel nausea at having to write this foreword, if I am honest with you.

'My son plays videogames' could mean absolutely anything, and part of the frustration is that people who think games are dangerous and terrifying do not have the ability or inclination to investigate them first-hand. There are so many barriers to a parent opening up a videogame. The first one is that the technology involved is expensive and baffling. The second, as Charlie Brooker says, is that once you are inside the game, it uses a language of play and interface that is like trying to learn Esperanto for the first time.

Almost anything can happen in 'videogames' these days. It wasn't originally like this. The more I learn about them, the less I know I know about them. I thought I knew what they were when I just played Street Fighter II on 'a Nintendo'. In that era they were neatly arranged through tropes – 'fighting game' or 'shooting game' – and now, well, I'm aware that there's so much more to all this than I thought. It is one of the most overwhelming concepts in the English language. People constantly try to recategorise them. 'Interactive experiences' could mean bloody anything. Walking a dog down the street is an interactive 'experience'.

But back to the book festival. She continues: 'He plays League of Legends for hours and hours on end. I'm really concerned for him. He does nothing else.'

Some sympathy. I nod: this too was a thing for me. The game might be interchangeable, but I am familiar with this kind of obsession. It happened to me because I needed to use my brain to problem-solve, but there were no problems in front of me, in reality, that could be broken down into granular, bearable problems. There were only monolithic horrible ones, that seemed, at least in the face of the monolith, to be totally impossible to solve alone. Some games provide these granular problems, and they are more easily solvable than, say, getting a degree, or getting a job, two things which at a particular time in my life seemed unlikely to happen to me without some sort of celestial miracle. Asking the question, 'What is wrong with this human who constantly wants to ignore the insurmountable realities facing him?' is not really a question about videogames. Constantly playing videogames is probably a symptom, I consider saying, but I know that it probably isn't what she wants to hear. That would sound like I blame his support network or his environment, or even our godforsaken country's politics. And those seem like insurmountable realities that she herself would find difficult to solve, as do we all.

For a moment, I think about League of Legends. My first instinct is to ridicule this game, as it no longer lies in my genre of choice (I am British; I like to ridicule everything). But as I think more deeply about my experiences with it, there's a lot there: it is a game that requires a bird's eye view of the overall goal, as well as an encyclopaedic, zoomed-in knowledge of the intricacies of items, upgrades, play-by-play tactics. But most of all, it is a team game. It is a game played over the Internet, in which you rely upon the grace and camaraderie of strangers. You can make friends there, good friends. It requires that you talk, or at least type. It is a game about communication through text and action. Most of all, it is a game about reading what is happening, and the behaviours of your opponents. It requires that you fail, and then get back up after failing. It requires that you weather caustic, awful people with some composure. It is a miniature anthill of human thoughts. In some ways, it is a very good education.

I raise my eyebrows for a second.

'I wish games were shorter. Maybe an hour long, and then they're finished,' she says. 'But this one, it doesn't end.'

Ah. Well, this is more in my wheelhouse, I think. You're in luck.

One great thing the Internet has given us is the ability to make games and distribute them for free to anyone across the globe. This has meant, in the past few years, that the distribution lines for compact game experiences have been busted wide open, and now there are hundreds upon hundreds of what people are given to calling 'independent games', for lack of a better term. These are games that are made on a very small budget, often to express one neat, compact idea or mechanical function. Sometimes they are free, and sometimes they are commercial.

I tell her that there are those kinds of games out there, and if she thinks it will help, she should encourage him to look into them: short, interesting experiences that can be finished in a small amount of time. Games like Nina Freeman makes, like Fullbright makes, like Brendon Chung makes. Small, linear stories that give you something intense, and then end.

I forget to tell her that there are people like Holly Gramazio, who design analogue games for outdoor play, or text games like Cheated on You by Ric Cowley, or vast space exploration games like No Man's Sky that will probably exacerbate her son's problems with switching off. I forgot to tell her that people are applying Heideggerian theory to games, as Zoë Jellicoe does in this book. But those are just some of the things I forget to tell her.

Here, where I live, videogames can be anything you want them to be. I recommend this book as a glimpse into what that could be.