Hilary Foister Benford grew up in England. As a child, she experienced the blitz bombings of World War II around London. She has a degree in French literature from the University of London and also studied in Cambridge, Strasbourg, and Paris. As a student, she worked various jobs in France as a waitress, hotel receptionist, chambermaid, and switchboard operator. She taught English at a French high school for a year and then taught French in both England and California. She married an American physicist and they have two children.

She co-authored Timescape with her brother-in-law Gregory Benford in 1980.

She has traveled extensively in 40 countries and still loves to travel. She has made a point of visiting all the sites where Joanna, sister of Richard Lionheart, lived, from Fontevrault to the Holy Land, from Sicily to Toulouse. She has a lifelong interest in history, languages, the Middle Ages, and her hobbies include genealogy, cooking, crosswords, and reading mysteries.

She currently lives with her husband in the San Francisco Bay Area.

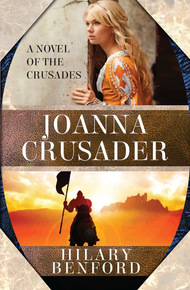

Joanna accompanies her brother, Richard the Lionheart, on the Third Crusade and is the only woman to visit Jerusalem itself (then held by the Saracens). She returns to France to learn that her brother has been captured and held hostage. With Richard's wife Berengaria, she works for his release. She marries for love, at a time when that was a rarity, but things go badly wrong when she finds that someone is trying to have her killed …

Crusade 1191

Chapter One

Joanna was furious. She was furious with the wind, with the waves, with her fellow passengers, and, especially, with God Himself. How could He allow this to happen? Did He not realize that they were sailing to defend His holy city from the unbelievers? Why would He risk the lives of the Crusaders at this juncture? She knew, of course, that she was being unreasonable. But being reasonable would mean being afraid, and she refused to feel fear. It was blasphemy, but she raged inwardly against God. All her life she had dreamed of seeing Jerusalem; God would not, could not, take that from her when she was so close.

The storm had come upon the Crusader fleet suddenly, around noon. The day had dawned fair, like all the others in the past fortnight. There was no sign of impending bad weather except for a brisk driving wind that bellied out the sail and lashed crisp peaked waves against the hull. Even the wide, slow-moving dromon with the women onboard surged forward and her brother Richard's swifter galley moved so far ahead it was almost out of sight, its scarlet sail a bright dot on the endless blue horizon. Then the dark clouds appeared, massed to the right, driven north from the coast of Africa. In a short time, the clouds overtook them and a wall of rain hit the fleet. The dromon lurched heavily and veered north, running before the wind.

Joanna was on the forecastle. When the rain burst upon them, she climbed hastily down the wooden ladder to take shelter beneath the forecastle, but there was no shelter there. She clutched at the railing, wondering why the Lord had sent this growling, purple-bellied storm at His holy warriors. The rain came low and angled across the deck. As the waves grew higher, the bow of the ship smacked into them, sending great arching sprays of water crashing and streaming over the whole vessel.

The sun had disappeared, leaving the sky dark from horizon to horizon except for a strip of blue far off to the east where Richard's red sail was no longer visible. A jagged streak of lightning cracked open the clouds and almost immediately, thunder banged and rolled overhead. The sailors crossed themselves and reefed the straining sail. The urgency of their movements focused Joanna's attention. Until that moment, the rain had been an inconvenience to be endured. Now she saw that the sailors were afraid and she shivered suddenly. The wind whipped her hood off her head and she dragged it back again, pushing wet strands of hair out of her eyes. With one hand she clutched her wool cloak at the throat and with the other clung to the post that supported the forecastle.

The ship pitched badly up the side of a wave and then down into the trough with a crash that sent a wall of water sluicing across the deck. In the waist of the ship, one of her women screamed as she slipped and fell. The tilt of the ship tumbled her across the rain-lashed deck like a sack of potatoes. Entangled in her wet cloak and skirts, she slid helplessly toward the stern as the boat climbed another wave. There was another flash of lightning followed by a corresponding crack of thunder that spread into rumbles all around.

Joanna's grip on the post tightened. They were so near now, only a week perhaps from the Holy Land, and this storm was driving them off their course, lengthening their journey, separating them from Richard and the main body of the fleet. She did not dare even think to herself of worse consequences, of shipwreck, of the mast struck by lightning, of the ship overturned and sinking through the dark churning water. The dromon was flat-bottomed, wide and stable: it would not sink. And surely they were under God's special protection, going as they were to recover His city from the hands of the infidels.

It was April, in the year of the Incarnate Word of Our Lord 1191. They had sailed from Sicily, which had been Joanna's home since her marriage to King William of Sicily at the age of 12. William had died in the winter of 1189, in the midst of planning to embark on this Crusade. God had not seen fit to let him live to sail with the Crusaders. Joanna remembered how envious she had been, listening to him making his plans. She would have given anything to go with him, but never for a moment believed it possible. His death had changed everything. Her lips tightened as she remembered the year she had spent as a prisoner in Panorme, confined to a few rooms of the royal palace because she would not support the bastard Tancred's claim to the throne.

But in the end Richard had come, as she had known he would. Of all her family, Richard had always been Joanna's favorite. Her first riding lessons had been given by Richard, the two of them sneaking out from the palace at Poitiers when everyone was at morning Mass. It was Richard who had defended her that time when she had interrupted the ladies and courtiers gathered in Queen Eleanor's rose bower at Poitiers when they were discussing whether love and marriage were compatible. Their mother had given in to Richard, as she always did, and allowed Joanna to join in their gatherings after that although she was only a child. Richard had defended and supported and teased her all through her childhood and she had worshipped him, her glorious, golden brother who loved being the center of attention, who could turn an aubade with the best of the troubadours and who had become the mightiest warrior in the West. When she left home at the age of eleven to marry the stranger, King William of Sicily, it was Richard who had ridden with her across France, down to the coast to Saint-Gilles where he had put her on King William's ship.

They had not known then, either of them, that one day Richard would be King of England. Their older brother Henry had been alive then and already crowned as their father's heir. Henry the Young King, poor handsome resentful Henry. He had died of a fever in 1183 and so Richard, who wanted only his beloved Aquitaine, had inherited the kingdom of England, the same year that Joanna's husband William died. Just a year ago Richard had sailed into Messina with all flags flying, forced Tancred to release Joanna and return her dowry, taken the city of Messina and built his insolent wooden castle of Mate-Griffon. It was in that castle at Christmas that he had broken his twenty-year long betrothal to the King of France's sister, and to that castle that their mother Queen Eleanor had brought his new bride, Berengaria of Navarre.

Less than a month ago they had sat there together, the four of them, Berengaria silent in a corner while Richard and his mother argued over the wedding date. Richard would not marry Berengaria then and there because it was already Lent. Queen Eleanor said in her usual brisk way, "Then you must take her on Crusade with you and marry her when you can." Richard was appalled at the idea. Had not he himself ordered that no women were to accompany the Crusade? Joanna felt sure that if she had not begged Richard to take Berengaria along, with herself as Berengaria's chaperone, he would never have agreed. But here they were, two thirds of the way to Acre to help the Franks recapture that city from the Saracens.

In the waist of the ship, at the foot of the tall mast, Berengaria knelt, surrounded by her Spanish ladies. With every lurch of the ship, the ladies wailed. Only Berengaria was silent. Lips compressed, pale, determined, she stared down at the crucifix she held in one hand. Slipping and sliding even on bare feet, the sailors lashed rope lines the length of the ship. The women were tied together like a string of ponies, one loop for each of them. They huddled together on the deck, clinging to their ropes, screaming and moaning. Their faces, open-mouthed and white with terror, seemed to rise above an undulating sea of sodden cloaks and skirts, pulled this way and that by the savage wind.

"Joanna! Look out!"

She heard Berengaria shout and half turning saw the wall of water that towered above them. She embraced the post with both arms and bowed her head as the water fell on her. The impact knocked the breath from her and the water, as it swirled away, tugged at her skirts and pulled her feet, but she clung firmly to the post, her arms locked around it, her eyes closed tightly.

The boat lurched sideways as the wind veered and there was a rending sound from the sail. Joanna opened her eyes and saw a great patch of the sail ripped across by the wind flapping in tatters. The mast bent before the wind's violence. Joanna stared up at it. At its head, Richard's standard streamed out, rigid. At the thought of Richard, she straightened involuntarily.

A sailor was beside her with a rope. He made to pass it round her waist but she snapped at him, "Take that away!"

"But my lady," he protested, "the master's orders are …"

"He orders me? I will not be bound like a sheep or a pig!"

The sailor hesitated, looking at her, but before he could speak again, another wave was upon them and he was driven against the side of the ship, still holding desperately to the rope. The women amidships screamed again. Joanna saw one reaching out for a sailor as she slid, bringing him down too to roll helplessly across the deck. The few knights they had with them were as abject as the women, she thought angrily, looking at them where they huddled beneath the aftercastle.

With a crack, the end of the yardarm snapped. The wind seized the dangling end of the sail and it tore away. The heavy wooden yardarm crashed to the deck, falling somewhere among the servants.

Beside Joanna, one of her women clutched at her hysterically.

"We shall die, we shall all die!" she screamed.

The women at the foot of the mast were screaming too. "We are doomed," she heard them wail.

Rage and energy rose in Joanna to meet the violence of the storm. How dare it do this to her, Joanna Plantagenet, daughter of the great Henry of England? She had a sudden vivid memory of her father standing on the prow of a ship, in a storm, though not such a storm as this. It was in the Channel; they were embarking from Normandy and King Henry uttered a prayer that sounded more as though he were defying God to sink his ship. Joanna could no longer remember his words, but she remembered Queen Eleanor's low laugh beside her and her sardonic comment: "Was that a prayer or a challenge?"

She and her mother had ridden out that same storm together across the English Channel when all but they and the sailors were seasick. They had not yielded to the elements then nor would she now. She would not die, she refused to die and these craven wretches were endangering them all. If they were all to pull one way in their struggles, they would break their ropes and tip the dromon. She shook her woman's hand from her arm. Another of the women was clutching at a sailor and he was struggling to free himself from her grasp. Without releasing her grip on the post, Joanna stepped forward and kicked her hard. The woman fell sideways, caterwauling, and the sailor lurched away.

"Pray, you blockhead!" Joanna shouted as the woman turned her face to her. Open-mouthed, the woman moaned and rocked from side to side. Joanna kicked her again. "Pray!"

Their minds were empty, the idiots, of all but terror.

"Deus noster refugium," she shouted but the wind whipped the words from her lips and hurled them away.

She leaned forward and bellowed at them. "Deus noster refugium!" Some more faces were turned to her now. They were her women, her responsibility, and it was up to her to keep their hysteria from spreading to everyone on board.

"God is our hope and strength," she shouted again in a break in the wind's howling. At the foot of the mast, Berengaria lifted her head and stared at her. Her eyes were huge and dark in her pale face, but her jaw was set. Joanna saw her lips move though she could not hear the words. Berengaria had understood and was following her lead.

"Therefore, will we not fear," Joanna went on, "though the earth be moved."

They had heard her now. One by one they picked it up. "Though the hills be carried into the midst of the sea; though the waters thereof rage and swell."

The waters were indeed raging and swelling and the wind was screaming and the ship creaking, but above the turmoil Joanna could hear them chanting with her. There was no screaming now. As though their lives depended on it, they shouted with her, "The Lord of hosts is with us; the God of Jacob is our refuge." The knights in the aftercastle had joined in, too. She heard them as a deeper sound underlying the shrill frightened voices of the women. The ship hurtled on through the waves, unpiloted as no pilot could steer it, tossing wildly.

The psalm had ended and they were all waiting for her. Another minute and they would be screaming and pulling at their ropes again. She needed a longer psalm to keep their minds occupied. What was the one about going down to the sea in ships? Another great wave fell across the deck and even as the first scream rose, Joanna found the opening line.

"Confetimini Domino … let us give thanks unto the Lord, for He is gracious …"

A furious energy possessed her, a spirit of defiance that would not allow the elements to steal from her, at its outset, this great adventure she had been longing for. Leaning forward from her post, she shouted the familiar words into the wind. "So they cried unto the Lord in their trouble and He delivered them from their distress." She no longer thought of what she was saying nor heard the chorus from the deck. She had to keep going, as though her words were driving them on, as though only her words could hold the ship together. She was free at last, free after years of being no more than an ornament at William's court. She was still young, and rich, now that her dowry had been returned to her, and she was sailing with the Crusaders, to see the Holy Land … Hastily she corrected her thoughts. Not for me, Lord, but for You, she prayed silently. They would free God's city, visit the holy shrines of His passion.

"For He brought them out of darkness and out of the shadow of death …"

Joanna's arms ached and her throat was sore from shouting above the wind.

"They are carried up to the heavens and down again to the deep … they reel to and fro and stagger like a drunken man …"

The ship was indeed lifted up to the sky and dropped again into the deep troughs, but no one was reeling and staggering. The sailors knelt on the deck, arms locked, braced against the rowers' benches. The women and servants crouched or sat along the center of the ship, lashed firmly together by ropes. In the stern, the knights knelt, too, and all of them faced Joanna, shouting with her.

"For He makes the storm to cease … and so He brings them unto the haven where they would be."

The master of the ship had come to stand beside Joanna. When the psalm ended, she stood there swaying, clinging to the post, unable to think of another. There was a pause and then a voice called, "Non nobis, Domine, non nobis," and they all joined in again, voices uplifted against the wind and the waves.

"I thank you, my lady," the master said.

Joanna had to bend her head towards him to hear what he said. His lips moved again but a rumble of thunder drowned his words. She looked up at him, a tall lean man with a dark beard. His eyes, narrowed against the cold rain, regarded her with admiration, even awe.

"What did you say?" she shouted.

He leaned towards her. Water dripped from his hair and nose and chin. "I said, now I see you are truly the sister of the great Lionheart."