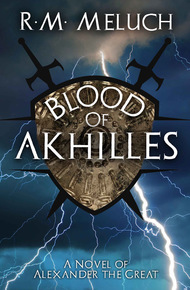

R. M. Meluch has been putting stories to paper ever since she could hold a crayon. She sold her first short story when she was seventeen. Got a big $7.50 for it. She is the author of the Tour of the Merrimack series with DAW Books. Her first story with WordFire was Dagger Team Seven in the Five by Five 2: No Surrender anthology. Originally from Ohio, she now lives in Pound Ridge, New York with her husband, Stevan Apter, and a bulldog, a Rottweiler, and a great white shedding thing.

King Philip lies dead in the theatre, struck down like a sacrificial bull on his day of triumph in front of all the subject nations of Hellas.

Twenty-year-old Alexander, son of Philip, must seize his father's throne and, harder still, he must hold it against his many rivals, who are Philip's veteran generals and noblemen, a royal cousin who was once crowned king in his infancy, and the secret conspirators who moved the assassin's hand, even as all the conquered cities of Hellas rise from under Philip's dead heel to reclaim their independence from the despised Makedones.

The task is overwhelming, but Alexander has complete faith in his own destiny and he quite literally changes the face of Hellas.

Born in the Dog Star's heat, on the sixth of the month of Loios, the very day that a wonder of the world, the great temple of Artemis at Ephesos, burned to the ground, Alexander was destined for immortality.

When such events collide, of gods and kings, such things are never coincidence.

Alexander is blood of Akhilles.

"R. M. Meluch is a terrific writer and I have long wondered why she is not better known. Like all of her books, the characters are finely drawn. The dialogue is witty and true-to-life. The plot is engrossing."

– Amazon ReviewWould that you had met your destiny

in the land of the Trojans and died there

while you enjoyed the kingly respect at your command.

Then all of Hellas would have made a monument for you

and you would have won great honor for your son thereafter.

But now, so it seems, fate decreed you be condemned

to a most appalling end.

–Homer, Odyssey, XXIV 30-34

Because he was blood of Akhilles, he was destined to die young. He did not fear it. He feared only to die old and forgotten, and no one remember the name Alexander.

He stepped out to the portico before first light. Behind him stretched the palace halls, black-shadowed, smelling of torch smoke and sea salt, quiet now but for the serving women, who moved like mice. And Alexander, accustomed to being first up, was last, but that was because no one else had gone to bed.

The wedding song had staggered on and off pitch half into the night, and by then it was time to go.

Alexander felt, couldn't see, the sodden heavens hanging low over him in the featureless dark. A chill breeze whispered with the breath of an early winter in the autumn just come.

He tried to fasten his cloak at his shoulder, the pin held in an awkward left-hand grip too close under his jaw. He could see nothing by the oil lamps' guttering flames. Shadows flapped, darker on darkness.

Distracted, rushed, he'd taken too thick a fold. Finally, he just rammed the pin at the wool.

The soft metal bent, turned in his hand, and jabbed hard.

He drew his hand back far enough to see what he'd done, and gazed in some surprise at the radiant gold sun pin neatly impaled in his palm.

There was no blood. The sun quivered slightly with his pulse.

He turned his hand over to see if the point had come out the other side. It hadn't.

A mantic would make something of it. There had been plenty of portents governing this day. He showed it to his companion.

"This one's easy," Hephaistion said. "The Makedonian royal house is in the palm of your hand. Securely enough, I'd say. You are your father's heir."

"It's in my left hand."

"I wouldn't stick it in my right hand to make it more lucky. The seer already said today is a good day. Here." Hephaistion grasped Alexander's wrist in one hand, pin in the other, pulled. Had to yank twice. The pin was in there harder than he'd thought. The sinews between the prince's fingers wrapped themselves around the metal and held.

"And just let anyone try to take it from you," Hephaistion muttered, yanked again.

The pin came out twisted.

A thin stream of blood ran down between Alexander's fingers and spread in a pattern like dead branches along the folds in his hand.

"Nothing has been easy." Hephaistion cleaned the pin on the edge of his own chiton where the red border extended below the leather kilt of his armor. "It's fate telling you what the king won't."

Alexander found a squat pail stowed behind a pillar. The pages had been purifying the palace in the wake of the queen's delivery. They had smeared all the halls with pitch, then washed them down with seawater. Barely got done in time for the princess's wedding.

Alexander dipped his hand in the pail, squeezed the sea sponge, salt water stinging.

A slow leak through the cracked clay left a spreading pool, so he stepped away carefully. He'd already skinned his knee on the glassy limestone steps earlier.

This was the old palace, its threshold stones worn to perfect smoothness by generations of foot traffic. The steps of the new palace in Pella—it wasn't even one hundred years old—those were marble, which was worse. When those got wet, you were better off barefoot.

Alexander shook the water from his hand. The slow bleed wouldn't stop. He made a fist.

"Put it over your head," Hephaistion said.

It was a trick they'd learned to slow bleeding, though neither could say with any real understanding why it worked.

Hephaistion straightened the sunburst pin, scraped its tip against a foundation stone to put some kind of point on it, then took it to Alexander's cloak, methodically working it through the dense stuff. When Alexander's mother wove him a cloak, she made it tight. Nothing passed easily through a web of Olympias's weaving.

"There."

Alexander moved to the rampart, set one foot to the low wall, and gazed into blackness.

Burnt smell clung to the fields, the harvest done, leaving the men free to make war.

Campfires spangled the plain below, like heaven turned upside down. And was it not? How else to explain an army that size without Alexander in it. He sensed the men out there, thousands of soldiers, though all he could see were the fires. He heard them like the murmurs of a distant sea, on this the last watch of the night.

All his life, since he could remember anything, the dream had been the same, to lead the greatest Panhellenic military expedition since the Trojan War. As he lived, the dream became a plan. The plan realized before his eyes.

He never once thought it would happen without Alexander.

Hephaistion drifted to his side at the rampart, his tall, gray-eyed shadow. Hephaistion was from Pella too. He had known Alexander all his life, the part worth remembering. They were, as near as they could tell, the same age, though they couldn't be certain. Only Persians kept birthdays. Hephaistion once asked his mother when he had been born.

"Middle of the night," her answer.

Everyone knew Alexander's birthday, as he had been born to be king. So everyone believed at the time.

A slight wind disturbed his blond curls. Alexander's hair always curled when it was cut too short.

Looks he had. Alexander's worst enemies couldn't deny that he was fair. He could have been taller. Real beauty required lordly height, and he didn't have it.

Persia's king did. Hephaistion did. Alexander stood no higher than an ordinary man.

Hephaistion leaned over the rampart with him. Low voices drifted up from the theatre carved into the foot of Aegai's acropolis hill like a giant broken bowl. The rising tiers had been filling in since midnight. Maybe earlier.

Kleopatra's wedding celebration was the biggest thing the kingdom had ever seen that didn't involve fighting for one's life.

Men conferred in low murmurs, afraid to break the charged stillness. Even the vendors, hawking breakfast honey cakes and figs, shouted only in whispers.

Torches lit the processional way that led to the theatre. In the shifting firelight Hephaistion could just make out the ribboned garlands of everlastings that cordoned the road. Hephaistion found them creepy, recalling the last wedding he and Alexander had attended, a disaster of thrown drinks, drawn swords, and a cold winter's exile in jagged mountains.

This wedding boded no better.

Alexander let his head tilt, his eyes fixed on the watch fires. "He gave the Companion Cavalry to Philotas." That command was always Alexander's, before the quarrel. "He said he forgave me, but he never gave the cavalry back." And he shivered, like the tremor in your arms when you've held the bowstring back too long. "So what am I? Which command is mine?"

The army numbered 40,000 men, bigger than most cities. Bigger than Athens, if you didn't count her women and slaves. Its front line could measure two miles across. Bivouacked, it took up the entire Emathian plain.

Tomorrow, the whole thing would be gone, nothing left but trampled grass, black fire pits, rubbish, and a lot of crows.

"Maybe he means you to be regent when he's gone. That can't be so bad. You keep saying the Triballoi will attack as soon as the army goes."

"He already named Antipater."

"Did he?" Hephaistion felt stupid for saying it.

Alexander nodded down, added in a moment, "I don't think he trusts me at his back."

"Then that means you're going to Persia with the army."

"As what? To leave me behind at the first hill town we liberate? I won't be proxenos of nowhere. I want my cavalry."

"It seems he means to surprise you."

And Hephaistion suddenly faced down a gaze so direct it startled. "Hephaistion, he doesn't have any plans for me. Everything he planned counted on Eurydike bearing a boy. Now he has to make something up in a hurry."

Alexander was capable of amazing stupidity regarding his father. A brilliant youth—beyond brilliant—Alexander concentrated all his idiocy around that one being, and could be boar stubborn about it. Boars can't back down. They'll run straight up your spear—which was why boar spears have those extra prongs on them, to keep the dying fury from running itself clean through and ripping you to bleeding slices.

"You have a seat next to the king in the theatre in front of absolutely everybody," Hephaistion said. "That has to mean something."

"What does it mean, Hephaistion? Exactly?"

"I don't know! Something important. We march to the sea tomorrow, so you'll need to know today. Whatever it is. By the end of this day you will know exactly what's meant for you."

"Then let's have done with it." Alexander pushed himself from the parapet with his foot and strode away.

Hephaistion's place this morning was in the cellar, guarding the treasury. His cavalry squad had a station in the parade, but Hephaistion had been pulled out and posted to a dark corridor. It was meant to be some kind of punishment. Not that Hephaistion had done anything wrong. He was the other half of Alexander. When the king was angry with Alexander, Hephaistion was in the cellar.

Hephaistion didn't want anything to do with the procession. The king had done him an inadvertent favor.

He watched Alexander go, and he spoke a parting softly after him. Didn't think Alexander heard, but in a moment Alexander circled back for something neglected in anger and haste. "I'll find you later. When your shadow is the length of a sarissa. Be nearby. You won't forget? Find me. If I'm still alive."

"Alexander!" Hephaistion cried against luck so foul even the speaking of it had its own power.

"I just—" Alexander opened his hand. "Feel my blood spilled on the ground today."

Hephaistion spat. "Horse shit." Spat again to be sure. "Only if you hold up Philip's parade. He'd skin you then. Get out of here."

Hephaistion listened as Alexander's running footsteps diminished into the perfect darkness that descends just before the light.

They would never know what his father intended for him this day.

O O O

I am the son of a harpy and the west wind.

I was foaled on the Ilion plain, and I was immortal. They called me Balios, for my coat was dappled then, in the days when Xanthos and I dragged Hektor's body three times around the walls of Troy.

I might have lived forever. I drew the chariot of the greatest warrior who ever lived. But I did not die with him, so my name fades, becomes as the wind, spoken now and then and quickly forgot. Do you remember the name Balios?

For one's name to live forever, one must die. That has always been the choice—if it is ever offered to you.

And to me was given what comes to few—a second chance.

After more than a thousand years, there would come another warrior like Akhilles. And it was asked of me: Will you live long and hollow as the wind or die with the new Akhilles and your name live bright and shining forever?

I chose. I said I would carry this new Akhilles to everlasting fame.

And I was transformed.

I am mortal.

My new coat is black and shiny as the night water. I am grand and tall and strong. I have a white blaze on my forehead. They say it describes the head of an ox. Well, they may say. I have seen it in reflecting pools. It looks like a daub of very white paint that ran a bit. And I did not get my name for the white blaze. Alexander has no such imagination in choosing names, and he's not the sort to see oxheads in a patch of white hair.

What I am named for I don't like to think on. You see, all heroes go to hell, and I took that journey.

No sooner was I become mortal than the ropes bit my skin. Metal stung my mouth, and hobbles bound my legs. When I tried to run I fell thrashing in the dust.

The men who caught me weren't warriors. They'd crept up on me while I stared at the strange darkness at my feet.

My shadow.

That was a surprise. I never cast a shadow when I was immortal wind. I had become a physical being. With a shadow.

It was my shadow that delivered me into slavery.

And I knew I had been tricked by whatever power with whom I had made this unholy trade. My life. My eternal life I had given up for dust and pain and metal bits.

You who have never been immortal cannot know my horror. The horror of a wish come true that should never have been made. I had bargained away everything.

And those brutes who tried to ride me! Such scum and low-borns that ought never have been conceived. They imagined themselves worthy to touch my back!

I would not have it.

I was peddled from idiot to idiot. No man could ride me.

As they loaded me onto a ship, pressed against senseless brutes, I screamed to heaven. I wanted to kill the god who had done this to me.

And I heard an answer, raging. Not the voice of a god, but an immortal nonetheless.

Xanthos!

Xanthos, who had shared the yoke with me and who had drawn Akhilles's chariot with me.

Xanthos's furious bugling carried on the wind out to sea. I got my head above all the other captives and saw him there, yellow Xanthos, rearing on the mound where Akhilles's and Patroklos's mortal ashes are buried.

Xanthos's voice followed me over the horizon: I will find you!

I truly thought he meant to.

At the end of the nightmare voyage, the ship put in at the port of Phthia. I had never been there, but Akhilles spoke of it. This was Hellas. Phthia was Akhilles's home.

Hope rose in my despairing heart. Was I then home?

But only more horror followed. Some cruel twist of destiny taunted me with this look at Akhilles's home.

I was driven overland to Corinth. Or Qorinth, as it was when the Hellenes used to spell the city's name with a koppa. The Hellenes don't use the koppa anymore.

Not as a letter. That mark is still in use. The koppa is also called an oxhead.

They use it to brand horses.

I remember the glowing metal brand coming at me. I who had never known a scar. They pressed red iron into my black hide. That stench filled my head. The pain. And rage, rage as only Akhilles has ever known. I crumbled to my knees, sick.

And rose up, broke the ropes. Turned on my keepers. Killed one of them. I thought my mortal heart would burst for all that I had lost. And I cursed that it did not. My heart drummed on, captive inside my chest.

I tried to find which god to curse. Who had offered me an immortal name and brought me instead to this?

I recognized what tears were when I shed them.

And, because I was mortal, eventually I had to sleep.

Then I was bound for auction. There would be a king at this auction. Such a king! they said. My captors counted the coins they might fetch for my magnificence, because this king was a powerful king. And I dared hope that he could be the promised one who would ride me to everlasting glory.

All the other horses at the auction were senseless brutes.

I shivered, waiting my turn.

They called at last, "Bring out the koppatia! Bring out the oxhead!"

I was nearly mad by that time, and went wholly mad when I saw their king. Their mighty king.

That. That could not be he. That was just a man. That was Philip, King of the Makedones.

My soul dropped out of my body.

Philip was a one-eyed brawny brute. Strong perhaps, wily as Odysseus perhaps, but no Akhilles.

He wasn't immortal. And no one would ever tell stories of Philip's horse.

I would not be ridden by that.

I lashed at him with my hooves, then pounded my shadow, that mark of my solidity. It was the stain of my betrayal. I wanted to be deathless wind again. I tried to stamp my shadow out of existence and become wind again.

Into my fury and despair came a young god. I hadn't seen him at first, for he was only a child then. A boy of just twelve, and not majestically tall for his age. He had golden hair and a voice as soft as a girl's, at least when he spoke to me.

When he took my head, I think I meant to kill him. But I felt the sure strength in his hands. And I knew. His strong calm was like water to the mortally thirsty.

This was the one. I had not been forsaken. It had only been a very long road here. I am for him and he for me.

Alexander has no creativity with names, so my name is still Oxhead. Boukephalos.

For as long as Alexander's name shall live, so will mine.

Since that day many men have seen the divinity in Alexander—after our first battle in the hills, after he founded his first city when he was still sixteen years old, after Chaironeia when he defeated the famous Theban Sacred Band.

We will live forever.

So it was that I knew, when Alexander came to me that dark new year's morning in Aegai. I knew that we had arrived at another kairos, a critical moment, a point on which the cosmos turns.

This was a crossroads in time. And crossroads are always dangerous.

Philip had contrived for big events to converge. Some mortals engineer their own destiny. And so Philip did on this, his day of days.

That morning Alexander called me from my pasture, and we set out over the dark, damp fields without bit or bridle or saddle or even halter. I carried him to where the wedding procession mustered on the plain.

A white bull lowed at Zeus's altar, awaiting the knives. The Makedonian royal house was god-sired. It was right that the procession began here in the god's temenos.

I high-stepped a path between gaily-ribboned oxcarts, milling celebrants, and nervous, giggling girls.

Torch flames dragged long with our passing, then snapped, flinging my shadow everywhere. My shadows don't scare me. I know that mortality is the price of eternal fame.

We found the king, Alexander's father, that hairy satyr dressed in a god's white robe. He wore a golden wreath on his black curls. Alexander hailed him. "Philip."

Alexander is a direct descendent of Akhilles, but not through this man. Alexander is blood of Akhilles through his dam. His sire is blood of Herakles. The get of Herakles are legion. And they're all drunkards.

A press of Alexander's knees brought me to a halt before the king. The ground was dew damp under my hooves. I stamped, ducked my head, and lifted with a guttural mutter.

I hope Philip did not suppose that was a bow.

Philip had wept tears of joy the first time he ever beheld Alexander on my back.

No tears, no joy, no pride on this, the last time he would ever see us.

Alexander kept his left hand still clenched to contain the bleeding from when he had run his hand through with a sunburst pin this morning.

Philip saw only the fist.

The eye raked us up and down, head to hoof. I think he coveted me, but he knew I was not for him. His own pretty white steed must have looked royally magnificent before I arrived.

And Philip's first words for his son were, "You can't ride that."

That. That was me. I was too grand.

Immediately Alexander swung his leg over my crested neck in a cavalryman's dismount. He pushed me at Philip's attendants.

These oafs found nothing to hold. I had come here naked. Alexander needed no tack to control me.

Philip's poor minions tried to get a rope on me.

I lifted my head up, my nostrils flared wide, and I reared. Showed them my teeth. I bugled and pawed the air. You must know I am a warhorse. My broad hooves are filed to a razor edge.

The men shrank back. The king's paltry white stallion danced, jerked its head against the tasseled reins of its royal headstall. It screamed at me. For all I care for the challenges of mortal brutes! That hack was nothing next to me.

And that was the problem.

Philip couldn't afford to have me next to his lesser mount. An annoyed gesture from the king bade Alexander assist his attendants with me.

Alexander took my head between his hands, and made me give attention to him alone.

We don't need them, I thought at him.

Alexander ground his teeth as if he had a bit between them.

He reached a hand out behind himself without looking back. A boy placed a makeshift halter into his hand. Alexander stroked my eyes shut and slid the leather straps over my face.

"Don't just come up and try to put something over his head," Alexander told the boy. "He thinks he's in battle."

And he gave my lead to the boy. To me he said, "Go with him. You're too grand, you know."

I knew. I heard it on the wind. This was Philip's day of destiny. I left him to it.

O O O

Alexander received in Boukephalos's stead a common sorrel, smaller than the king's snowy mount. Brushed, caparisoned, docile, gelded.

The king's right side was reserved for the bridegroom, Alexander Neoptolemou, king of Epeiros.

Alexander, son of Philip, would ride on the king's left. Whether this was to honor the bridegroom or to keep Alexander on the side with the sighted eye, no one said.

The story had gone round several times now that Philip lost his eye while spying on his wife as she coupled with the serpent that fathered Alexander. Though Philip never actually witnessed such an act, he didn't doubt the truth of the fucking snake. But as for its begetting Alexander, the boy was already well got before Philip lost the eye. It was a bolt at the siege of Methone, not a god, that had done the damage.

Alexander had been little more than a baby when Philip came home with that wound. A strange man Alexander didn't know, a distant rumor called Father, Philip, the King, who was away at war. Then, to the babe who lived in the doting world of women came a booming voice, a bristly black-haired face with a gaping red hole in it where should have been a second eye. Alexander remembered the smell. He'd just been told a story and he screamed, "Cyclops!" as best he could pronounce it.

Philip said he didn't remember that.

Alexander also remembered Philip telling him, urgently, "Don't ever lose, son. They'll eat you alive if you lose."

Here on the plain with his armies, Philip caught sight of Alexander before Alexander saw him. Alexander was difficult to miss. Golden-haired, easy as a centaur on that giant stallion of his as he came, collecting adoring glances from everyone he passed.

Alexander's eyes were full of melting softness for his horse in farewell. The soft gaze iced over hard when it turned on Philip.

Philip had met less malice across a battle line. Where had the boy got those eyes?

Philip was grateful that he'd never seen a blue-eyed snake.

On a normal day Alexander was as talkative as a magpie. From him now came only that glare. Philip mistrusted his son's silences. Alexander had a deep well for wrath. His bloodline was famous for it.

Philip prodded. "Have you nothing to say to me, boy?"

Alexander's face looked every bit as cold and hard as his carved marble likeness at Olympia.

"What do you want from me, Philip? Did I forget to congratulate you on the birth of a legitimate Makedonian daughter?"

"You mean-spirited cur pup," Philip breathed.

"I see the ribbons over the door are royal purple," Alexander said.

Ribbons for a girl.

They should have been olive boughs. It sickened Philip to see all those olive branches thrown into a trash pit. Hundreds of them.

He'd been so sure the child was a boy. It had to be a boy.

There'd been a hideous, humiliating scramble for ribbons to announce yet another princess.

The ribbons' color need not have been royal purple. But there they were.

"Her mother is the queen," Philip snarled at Alexander. Philip was not setting his new queen aside just for that. And he wasn't taking back Alexander's mother for anything.

"So who would be riding at your side today if you'd hung olive boughs over the door?" Alexander asked.

"It's a girl, not a boy!" Philip owned his defeat. "So you pray louder than I do! Why are you rubbing my nose in it on my day?"

"You meant to replace me."

Philip's mouth dropped open to startled silence, then stammered to get something out. "Replace you! Replace you? I wish I could! It's a curse! All my sons as they get older suddenly get stupid!"

He was shouting at the end of it.

The sound rang from the resonant barrel of his chest, and damped down all the surrounding murmurs.

Musicians, maidens, high-ranking Royal Companions, pages turned to look.

"Why would I have you here at all if I could replace you!"

"To break my mother's heart."

The boy's mother, Olympias, was in Epeiros, the land of her maidenhood, a place of wild mountains, murmuring oaks, wolf dogs, and golden eagles. Clouds brushed the jagged spine of mountain peaks that walled off the kingdom of Epeiros from the rest of Hellas. Its sunless valleys hugged bitter shadows.

The gates of hell were in Epeiros.

So was Alexander's mother.

This wedding forged a new bond between the Epeirotes and the Makedones. This wedding meant Philip would never bring Olympias home again. Ever.

Philip bawled, "What makes you think that what I do has anything to do with your serpent-infested mother!"

Alexander's gaze, so cold it could burn, found the bridegroom, the king of Epeiros. He was yet another Alexander, but everyone called the Epeirote king Neaptolemou for his father.

Philip's son Alexander spoke at Alexander Neapotolemou's eyes. "Mother has always been surrounded by serpents."

"Don't talk past me, boy! You are talking to me. Talk to me!"

"Why am I here, Philip?"

"You are here because you are my son. My least idiotic son. If you don't want to be here, go be Myrtale's son!" Philip roared.

And watched the boy's face go bloodless.

Philip almost wished he could take it back. He'd meant to hit him hard, but Alexander suddenly looked like a man with a spear in his gut. Well, the boy had asked for it. It would teach him who was the absolute ruler here.

O O O

The ground heaved under Alexander's feet without actually moving. He was still finding his balance when someone sidled up to him on a black gelding.

Perdikkas's crooked mouth made him look like he was always smirking. He usually was. Perdikkas, lord of the Orestids, was ten years Alexander's senior, a seasoned general.

Brash, reckless, full of his own noble privilege, Perdikkas would poke a wounded badger to see how much life was left in it.

"Alexander! What did he say to you?"

"My mother's name is Olympias." The words escaped from Alexander's stone white lips.

"Of course it is," Perdikkas said. "Don't speak in dark sayings. I never get 'em."

"Her name has been Olympias since the day I was born."

"Oh. Well. That explains it," Perdikkas said, all at sea. "Alexander, what did he say?"

Huge eyes lifted to Perdikkas. The black disks of his pupils nearly eclipsed the surrounding blue. "He denied her name."

The deposed queen had been called Olympias for so long that Perdikkas forgot that Olympias had ever been named anything else.

She used to be Myrtale.

Philip had given her a new name when his chariot won at the Olympic games. He'd re-named her Olympias and acknowledged her newborn child, Alexander, as his son and heir.

Now she was back to being Myrtale again.

"He called me a bastard," Alexander said, just in case Perdikkas didn't get it.

Perdikkas got it.

"No. Philip just—" Perdikkas searched, sputtered. "You are such an easy target! And if he threw a javelin at you, would you just stand there and eat it?"

"He should learn not to throw at me."

"Not going to happen. He's Philip. That's how he is."

And Philip was moving back in, on foot, shoulders hunched in a charging-bull posture.

Even rash Perdikkas, who had more courage than sense, fled the battleground, never one to eat javelins.

Alexander didn't wait for whatever Philip was coming back to say. Alexander sat tall on his mount and cast first. "To my face, Philip. Deny me to my face."

Came the low rumble of fire within the mountain: "Don't dare me. Get down here."

Alexander swung his leg over his gelding's neck and dropped to face his father.

"There it is, Philip. Let's have it. Put someone over me! Who have you got?"

Philip grabbed his own balls. "I got lots where you came from, you yapping Epeirote mutt! Sons! Lots of them left in here. Taller ones! Grateful ones! And you are swallowing all this!"

Philip flung his beefy arms wide to heaven. "You are gullible as a girl! Look at the color of your cloak! That is royal purple. You are riding at my side today. My side. Your seat is next to mine in the theatre in front of all the Hellenes. I didn't divorce you! Now go collect your wits wherever you left them this time and come with me. They're ready for me at the altar."

Alexander remained rooted to the spot. The man could change on him as sudden as the sea. And Alexander never had any special love for the sea.

"Or don't come!" Philip flapped his arms. "Leave the purple chair empty! Do what you will. You always do anyway."

The gaze stayed fixed on Philip, frighteningly near to tears. Alexander's nostrils quivered. The boy was full of words, but saying none of them.

"What?" Philip heaved.

"I need to know."

"You need. You need. I'll tell you truly who is my heir. Do you want to know? Do you? Come here." Philip waved him in. "Come."

Alexander advanced like a tree walking.

"I swear to you by—by any collection of gods you like—"

"By your own balls."

"By my balls. This is the truth: My kingdom shall go to the strongest."

"And who do you imagine that is?"

"He is who he is, and that is my last word."

"You won't name me."

"My last word."

And harpies take him, he'd gone silent again! Philip stalked away.

I will be jubilant today!

How the soil bent the seed that there should be so much of her in him. Olympias was as vicious and evil-tempered as the horses from that jagged land. Would that he had got Alexander on some other woman!

The boy was headstrong. Arrogant. And Philip would not love him otherwise.

What a son he had made!

It gnawed at him like Prometheus's buzzard that he hadn't been able to do it again.

He spun back. Thundered. "I will not hand you the kingdom as a gift! There will be other sons! Rivals will be good for you! You can work for what you want! If you get this kingdom, you will earn it on your own!"

As Philip turned away he felt the hatred at his back.

The wrath.