T. Kingfisher is the vaguely absurd pen-name for children's book author Ursula Vernon. This is the name she uses to write books for grown-ups. Under various names, she has won the Hugo, Nebula, WSFS, Mythopoeic and Sequoyah awards. She lives in North Carolina with her husband, dogs, cats and chickens, and when not writing, she likes to wander around the garden and try to photograph weird bugs.

When Gerta's friend Kay is stolen away by the mysterious Snow Queen, it's up to Gerta to find him. Her journey will take her through a dangerous land of snow and witchcraft, accompanied only by a bandit and a talking raven. Can she win her friend's release, or will following her heart take her to unexpected places?

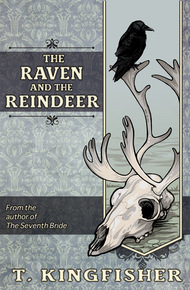

A strange, sly retelling of Hans Christian Andersen's "Snow Queen," by T. Kingfisher, author of "Bryony and Roses" and "The Seventh Bride."

T. Kingfisher is a multi-award-winning writer with a taste for odd tales. The Raven and the Reindeer offers the well-loved fairy tale ingredients of witchcraft, talking animals, a daring quest and the Snow Queen... I love strange, quirky tales and was delighted to secure this one for the bundle. – Charlotte E. English

"…the research into Finnish customs and Scandinavian living is excellent, and blended perfectly into the narrative without becoming pedantic. It's just such an indulgent joy to be part of Kingfisher's worlds. I want nothing more than for her to take on every single one of Hans Christen Anderson's stories (and the Grimms', while we're at it) and remake them in her own style, so that I can go on indulging in them forever."

– GeeklyInc.com"Simply magical. If you haven't read this one yet, it's the ideal book to curl up with a cup of hot cocoa and a blanket and read on a cold winter's night."

– SFBluestockingOnce upon a time, there was a boy born with frost in his eyes and frost in his heart.

There are a hundred stories about why this happens. Some of them are close to true. Most of them are merely there to absolve the rest of us of blame.

It happens. Sometimes it's no one's fault.

This boy was named Kay. His eyes were blue when he was born, pale as a winter sky. The frost glittered in them, in little flecks of silver around the pupil.

"What lovely eyes!" his grandmother said, rocking the baby on her knee. "He'll be a devil, with eyes like that."

"Lots of babies have blue eyes," said her best friend, who was knitting baby clothes. "They mostly grow out of it."

His grandmother clucked her tongue. "You won't say that when your grandbaby's born."

"I will, too."

"You would, wouldn't you?" Kay's grandmother laughed at that, and her friend smiled. "They'll be great friends, our grandbabies."

"If they don't grow out of that, too."

"Oh, you…" Something displeased Kay and he screwed up his face and squalled. "There. Your eyes will stay blue. Don't listen to that old sourpuss."

The old sourpuss in question only laughed.

The granddaughter was born a few days later, and her eyes were brown. They named her Gerta. She was chubby and good-natured and slept easily through the night.

Kay grew up tall and slim and his eyes stayed pale blue with a ring around them, like the eyes of a sled dog. His grandmother had been right about that.

Whether or not she was right in her other prediction was an open question.

Gerta would have said that Kay was her best and truest friend, that they could tell each other anything and they would take on the world together.

Kay would have said Gerta was the neighbor girl. "She's all right. I guess."

In fact, he did say this, on a number of occasions.

There are not many stories about this sort of thing. There ought to be more. Perhaps if there were, the Gertas of the world would learn to recognize it.

Perhaps not. It is hard to see a story when you are standing in the middle of it.

But if Kay had a sled-dog's eyes, Gerta had a dog's loyalty. It did not matter that he ignored her sometimes, or said "It's just the neighbor girl" to the other boys in the town. Those boys did not know what Gerta knew.

When it was cold (and it was often cold) when the snow was piled four feet deep under the eaves (and sometimes higher) then Kay would open the window in his family's garret and Gerta would open the window in hers. They were separated by less than three feet, and there was a little bit of a bridge between them, where Gerta's mother had set up a windowbox.

Then one or the other would step across the gap and into the other one's home. On cold days, the stove would be on and there would usually be something delicious on it—lingonberry juice or mulled cider or a plate of gingerbread.

The two of them would play together for hours as children. They were not much alike. Kay liked puzzles with pieces that you could fit together, and Gerta liked making up stories of heroes and gods and monsters. Gerta was only taller than Kay for three glorious months, when she got her growth spurt and he didn't. Then Kay shot up past her and Gerta never got any taller.

"That's just the way it is," her grandmother said. "We're short, sturdy people. Keeps us below the level of the wind."

"I'd rather be tall and beautiful," said Gerta.

"If wishes were fishes, we'd have herring for dinner."

"We're going to have pickled herring anyway," said Gerta.

"Well, then who knows?" Her grandmother winked at her. "Perhaps there's some point to wishing after all."

As they got older, the children would talk—or Gerta would talk and Kay would comment occasionally, his slow sentences falling quiet as snowflakes.

"Sometimes I think that snow could be alive," he said once. "Like a hive of bees."

"I always think of feathers," said Gerta. "Like what if a snow goose flew over us and all the down shook out of its feathers?"

"It would have to be a big goose."

"Or a whole flock of them," Gerta agreed. "A whole flock of geese over the town, flapping their wings, and that's why it's windy too!"

Kay smiled faintly.

Another time he said, "I like the world better when it's snowed. You can't see all the ugly bits. It's all pure white."

He did not know that Gerta treasured these statements, saving them up and repeating them to herself at night. They were her great comfort. In summer, when he went around with the other boys and pretended to ignore her, she remembered his words.

She thought, I bet he doesn't say things like that to the other boys. That's the part of himself he only shows to me. That's the important bit.

Which only goes to show that you can be both right and completely wrong, all at the same time.