Gray Rinehart is the only person to have commanded a remote Air Force tracking station, written speeches for Presidential appointees, and had music on The Dr. Demento Show.

Gray retired from the U.S. Air Force after a rather odd career. He began as a Bioenvironmental Engineer, became a project engineer, then became a space and missile operator. Over the course of his career, he kept rocket propulsion research operations safe, fought fires as head of a Disaster Response Force, trained Air Force ROTC cadets, refurbished space launch facilities, "flew" Milstar satellites, drove trucks, processed nuclear command and control orders as an Emergency Actions officer, commanded the Air Force's largest satellite tracking station, protected militarily critical space technologies, and wrote speeches for top Air Force leaders.

Gray is a Contributing Editor for Baen Books, and his fiction has appeared in Analog Science Fiction & Fact, Asimov's Science Fiction, Orson Scott Card's Intergalactic Medicine Show, and other venues. Through a quirk of fate, his story "Ashes to Ashes, Dust to Dust, Earth to Alluvium" was a finalist for the 2015 Hugo Award for Best Novelette. He is also the author of a variety of essays, articles, and other nonfiction, and a singer/songwriter with two albums that feature science-fiction-and-fantasy-inspired songs.

Gray's "alter ego" is the Gray Man, a famous ghost of Pawleys Island, South Carolina. For more information, visit graymanwrites.com.

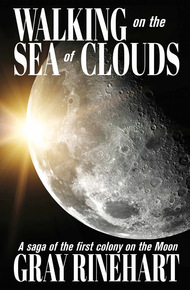

Before permanent lunar encampments such as Clarke's Clavius Base (in 2001: A Space Odyssey) or Heinlein's Luna City (in The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress) could be built, there would have to be the first settlers—the first people to set up shop and try to eke out an existence on the Moon. Walking on the Sea of Clouds is the story of such lunar pioneers: two couples, Stormie and Frank Pastorelli and Van and Barbara Richards, determined to survive and succeed in this near-future technological drama about the risks people will take, the emergencies they'll face, and the sacrifices they'll make as members of the first commercial lunar colony. In the end, one will decide to leave, one will decide to stay, one will put off deciding … and one will decide to die so another can live.

"This is hard SF at its hardest—by which I mean that not only is the science spot on and largely off-the-shelf, but the characters conform to the emotional and psychological limits of folks we interact with every day. There are no galactic crises to be overcome, no interpersonal conflicts that erupt into homicidal rage, and no cast of quirky tycoons, femme fatales, or wise-cracking test-pilots. This is the Moon as it's likely to be in the early days of colonization, where even the smallest problems have impacts far beyond what living on Earth has trained us to anticipate."

– Charles E. Gannon, author of the award-winning Fire with Fire"There is a very rare and special pleasure that comes from reading a beautifully written book from a true expert in his field. In reading Walking on the Sea of Clouds, it immediately becomes apparent that Gray Rinehart is intimately familiar with the field of near-future space exploration. He understands what it will take to get mankind to the moon and beyond. He writes about the military as only someone who has been in the military can. He writes about bureaucracies and funding in the way that someone who has struggled with them does. When it comes to astronauts and space exploration, his characters ring undeniably true."

– David Farland, author of the NYT-bestselling Runelords novelsWisdom Has Nothing to Do with It

Sunday, 29 October 2034

It should have been a perfect Santa Barbara Sunday.

It seemed like a perfect Santa Barbara Sunday, but all day Stormie carried a ticklish feeling in the pit of her stomach that something was about to go wrong. As the day progressed she let herself relax, but when the crisis came she rushed in—"ahead of those frightened angels," as her grandmother used to say—and learned how badly doing the right thing can backfire.

The morning started perfectly. They woke early to watch the colony setup team launch on the Asteroid Consortium feed, and Frank distracted her in his not-so-subtle way. Sweaty and spent, she lay with her head on his chest and dismissed the nervous tickle as a sympathetic reaction, anticipating their own launch still six months away. It was low in her gut, as if she could feel the subsonic rumble when the engines ignited even though they were 7500 kilometers away from the French Guiana launch site.

The afternoon offered its own version of perfection. They strolled down the TechnArt alley along East Beach, invigorated by the clear, cool day. Musicians vied for their attention as they passed ingenious tech-infused artwork and multisensory productions; they paused frequently but bought only a three-in-one piece the artist called a "digital triptych." Stormie credited the twinge in her belly to disappointment that the only art they could take with them was digital.

She relaxed enough to enjoy their early supper at Bucatini—superb, if a little pricey compared to the restaurants they frequented back home in Houston—and did she feel a bit of indigestion when they came again to the beach to catch the last of the sunset?

The winter solstice was still eight weeks away, so the Sun wasn't as far south as it would eventually go, but it sank into a magnificent ocean vista, turning the low, thin clouds vivid orange.

"Red sun at night," Frank quoted.

The cool breeze massaged Stormie's bare arms. Frank had offered her his coat, and Mother Mac's voice in her head—"Don't wanna catch cold, child"—urged her to accept. But with Frank's arm around her she had warmth enough.

"I hope they're okay," she said, the tickle inside her a counterpoint to the thought of "sailors' delight." By now the team should be close to boosting out of Earth's orbit into cis-lunar space.

"Should we check?" Frank asked, though he did not reach for his CommPact. He traced a pattern on her upper arm, his fingers strong and gentle.

She wanted to, but said, "No, if something had gone wrong someone would have called."

Frank nodded. With his free hand he scooped up some sand and squeezed it; Stormie enjoyed the smooth tension of his muscles as he involuntarily held her a little tighter.

"Yes," he said, "I am certain James would let us know."

Stormie smiled at his formal speech; his teachers had emphasized very proper English, and Frank always learned his lessons well.

The breeze strengthened, and brought a heavier hint of winter cold. Stormie dug her toes deeper into the rapidly cooling sand to get them out of the wind. She huddled closer to Frank, more for company than for comfort.

"Would you like to go in?"

"No, let's see the Moon come up."

They talked about the day, the art and music and dinner, always circling back to the lunatic dream—in the purest sense of the word—they had been pursuing together. Gradually stars emerged in the twilight, but only those bright enough to shine through the high haze and penetrate the ambient light from the city behind them. The old oil wells in the Channel provided their own version of romantic illumination from the still-burning platform lights and gas flares, but that didn't help with seeing the stars.

The last vestiges of twilight fell away into night, and the waning gibbous Moon, just two days past full, crept upward behind the cloud layer. It should be close to lunar high noon over Mercator Crater, their eventual home on the southern edge of Mare Nubium.

As the silence lengthened, Frank recited from Noyes' "The Highwayman." "The Moon was a ghostly galleon—"

"That's what you always say."

"That is what I always think, when the Moon is in clouds like that. Have you found another verse, a better one?"

She shook her head. "No, and not for lack of trying. I should be able to come up with something, but I can't." It was a game they played from early in their dating life—

Motorcycles tearing up and down Cabrillo Boulevard drowned out whatever reply Frank made. They faded in the distance, and Stormie closed her eyes and listened to the gentle, soothing waves.

"A shekel for your thoughts," Frank said. The words rumbled through his chest; Stormie felt as much as heard them. She didn't mind his interrupting her reverie.

"I'm just listening to the water. It's nice to sit here—out in the open, I mean. It'll be hard to leave this behind."

In his slow, rolling cadence, with the distinct Kenyan rhythm that comforted her, Frank said, "Yes, it will. But even if it is hard, I do not think it will be so very bad. We are committed now."

Or we ought to be. "Do you really think we're doing the right thing?" she asked.

"I have no doubt. How many people get to be pioneers?" His words blended into the rolling waves, and he dropped the remains of more sand she had some moments before dribbled into his hand.

"You didn't always sound so sure," Stormie said, wondering as she often did if she had asked too much of him. To some degree her passion for the project had influenced his.

"That is true. But … it is one thing to tend to plants and trees on a living world, to help sustain it, and quite another to try to bring a dead world to life." He brushed his hand on his pants.

Stormie smiled. "We should go back soon. Then let's get up early to see the sunrise."

"I think we can do that, and still meet James for breakfast. And even if we are late, I am sure he will not begrudge us—after all, we will soon use up our allotment of sunrises. I hope our new ones are splendid enough to make up for having only one a month."

"I just want to be done with all the prep," she said, and her stomach tightened. In a few weeks they would undergo one final test to see if they had what it took to live on the Moon: ninety days in long-term isolation, buried with other trainees in an underground center. Anticipation and frustration swirled together inside her; she wanted to launch now, not wait any more or go through more training. After so many months of preliminaries, to have to go through one more phase seemed almost impossible. Maybe that was the point: it was a marathon rather than a sprint. But she'd always been a sprinter. "I can't believe it'll be almost two years by the time we launch."

Frank laughed. "Imagine how much longer it would have been if we worked for the government. But even so, it has been much longer than two years, my love."

Stormie counted back the months, and shook her head. "Maybe if you count setting up the company, two years ago next month. Then, if we launch in May, that'll be twenty-eight months." Although we started talking about it right after Jim's accident, and that was over three years ago. "I was counting from last August, when we won the contract, so it'll only be twenty months."

Frank shook his head, and swayed with the motion. "No, my love, you have forgotten. I am sure we have been talking about this as long as I have known you—six years or more. On our second date, if I recall, you talked about some nanoparticle breakthroughs in one of the orbital stations. And I believe you mentioned on our third date how much you wanted to fly away into space."

She smiled, but only at his lilting diction. She had forgotten both of those conversations; if they had just started dating, that would've been when they were in that astronomy elective together. She vaguely remembered the station experiments as being one of the more profitable ventures for either Low-Gee or OrbiTech; that would've been a reasonable topic, just an extrapolation from their coursework. But … she gave Frank a soft jab to the ribs. "No, I didn't."

"Oh, yes, my dear. And on the one-month anniversary of our first date, which I still do not comprehend the meaning of a one-month anniversary, you gave me an article about the move to enact a new Space Treaty—"

"I don't think so, Frank."

"And you wanted to write it into our wedding vows.…"

Stormie looked up into Frank's face. In the shadows only the whites of his eyes were visible. If you felt like I was badgering you, why'd you ask me to marry you in the first—

Frank smiled then, and his teeth were almost bright enough to blind.

Stormie leaned in and kissed him. The evening seemed warmer still, and the flutter in her stomach was anything but apprehension. Her enthusiasm buoyed her, and she held on to Frank for fear she might float away to the Moon without him.

* * *

A little later, they walked east along Cabrillo toward their hotel. Frank had insisted that Stormie wear his sport coat, and it hung on her almost like a short dress.

His words were drowned out as two black-clad daredevils on crotch rockets sped past them up Cabrillo.

"What did you say?"

"I said, perhaps we should go dancing." To emphasize his point, he raised her hand and, touching it lightly, revolved himself around her like the Moon around the Earth.

Stormie didn't break stride, but she chuckled at him and shook her head. "It's been a long time," she said. "And I don't know where we could go."

"That is fine, my love. We can dance right here." He danced another turn around her as she walked, and started a third as the motorcycle jockeys came roaring back the other way.

Just in front of her, Frank slowed, with a puzzled look on his face, as her mind registered unexpected sounds: brakes; an impact and then another, louder one; the crunch and groan of crumpling metal; the distinctive crackle of breaking glass. Puzzlement turned slowly to surprise on Frank's face and his momentum carried him halfway around her.

Stormie turned with him, and the tickle in her stomach solidified into jagged granite.

A little silver Ford—one of the new fully-automated Dragonelle turbine/flywheel models, just like their rental—and a black or very dark blue older model Nissan had hit headlight-to-headlight a dozen meters away. A thousand sparkling bits of glass littered the street around the cars. To the left, a minivan was up on the sidewalk, resting against one of the palm trees lining Cabrillo. A black-clad figure lay unmoving on the pavement.

By the time Frank came to a stop, he had pulled Stormie halfway around. She glanced at him, looked back at the crash, and took a step toward the vehicles. Frank tightened his grip on her hand to hold her back.

She pulled against his hold. "Come on," she said, "we have to help."

He kept his grip on her. "Do you think that is wise? We have to—"

Stormie shook her head. Wisdom has nothing to do with it. "We have to help, if we can. Now. I'll see if that biker is okay, and you call 9-1-1." She tapped her right foot, twice, then pressed it down a little behind her as if she were settling into her old starting blocks.

Come on, Frank. If we don't help, no one will. No one ever helps.

"Very well," Frank said. He held Stormie's hand a second longer. "Be careful. No unnecessary risks." He kissed her hand; she squeezed his, trusting him to move when she did.

She sprinted toward the dark shape on the street.