Steven Poole is the author of Rethink: The Surprising History of New Ideas, Unspeak, Trigger Happy, You Aren't What You Eat, and Who Touched Base In My Thought Shower? He writes on science, language, and culture for the Guardian, the Wall Street Journal, and many other publications, and writes a monthly column on videogames for Edge magazine.

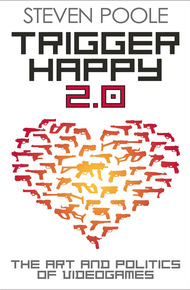

Why can't a wargame be anti-war? Why does "gamification" spit on the downtrodden? And why do so many videogames take the form of boring jobs? Investigating the aesthetics, politics, and psychology of modern videogames, the mini-essays in this long-awaited follow-up to 2000's Trigger Happy are an edited and revised selection of Steven Poole's much-loved columns for Edge magazine. In it, you'll find out why the Tomb Raider series is like the oeuvre of Mark Rothko, why Nietzsche might have enjoyed Donkey Kong, and what "self co-op", "cognitive panic" and "unreliable agency" mean when you're gripping a joypad or clawing at a mouse.

"The Edge columnist presents edited and revised versions of some of his vintage columns for the notable video game magazine - beautifully thought-out musings on culture & games." – Simon Carless

"Throughout Trigger Happy 2.0, Poole demonstrates the imagination to see things in an unusual way and the confidence to know that he's right, and that slam-dunk accuracy is his secret weapon … wildly energising… If you read about games, it's focused literary joy."

– Eurogamer"Splendid… witty, comprehensive and passionate"

– The Times"From the design standpoint, I haven't seen any better history of the game industry, and more importantly what that history means, than Steven Poole's Trigger Happy"

– Ernest Adams, GamasutraNational-Security Ideology

News just in at the time of writing: speculative venture capitalist and "hater of our freedoms" behind telegenic acts of mass murder shot in the face by Navy SEALs flying in on stealth helicopters into a secret compound next door to Pakistan's main military academy. Target's mangled face identified using secret "face recognition" software; body dumped in the ocean. Nothing to see here; move along.

Not exciting enough? Now you can play it yourself. The news that the shooting in the face — or what a friend of mine took to calling the "very brief capture" — of Osama Bin Laden was almost instantaneously turned into a downloadable Counter-Strike map seemed to me a heartwarming demonstration of the creative irreverence of the videogaming world.

If Barack Obama had really wanted to take the nephritically challenged Christopher Lee lookalike alive, the President should have demanded that the SEALs be armed with guns featuring those videogame-style reticules that turn into an X when you point them at someone you're not allowed to shoot, disabling your trigger for good measure. (Human nature being what it is, whenever I get such a reticule I start pumping the trigger hysterically, so that when, without warning, I am suddenly granted shooting privileges again, I find myself spinning round in an unsurgical frenzy of "happy firing", the joyous loosing-off of AK-47 ammunition that traditionally accompanies Afghan weddings, sometimes with tragic results.)

If taking Osama bin Laden "dead or alive, or, you know, dead" in his mazelike Abbottabad "lair" had really been a videogame — as implied by the Photoshopped pictures that quickly circulated of Obama watching the raid while holding an Xbox controller — the cadaverous white-robed boss would hardly have just been standing there unarmed in the final room. He would have been surrounded by hundreds of explosive wives and children, rolling fast towards the player in earthshaking waves, while the big man himself beamed orange incendiary lasers from those haunted deep-set eyes and occasionally spin-attacked around the room like some pirouetting razor-bearded maniac on fast-forward.

Compared with such dramatic possibilities, the reality disappointed, as it so often does: indeed, as the official story morphed and corrected itself, the mission to kill or capture (or, you know, kill) bin Laden seemed increasingly tawdry and one-sided. What Navy SEALs are tasked to do in real life is not much like what they do in videogames. (For a start, in games you are always part of a small squad facing massive numbers of hostiles: in reality, commanders prefer to establish a scenario in which you are part of an overwhelming force.) But the whole episode, with its refreshingly impious Counter-Strike coda, might also cause us to reflect anew on how what one might call "national-security ideology" is uncritically internalized in so many videogames today.

Take Splinter Cell: Conviction. Periodically throughout the game you meet a person whom you are not allowed to shoot (hello, white-X reticule) but must instead "interrogate", basically so that you know which door to go through next. Pressing B in response to the repeated on-screen prompts to "interrogate" each such person results in your character performing various acts of close-up violence: smashing a guy's face into a desk; pinning him against a wall and choking him; kneeing him in the stomach, and so forth. This kind of thing is what the Bush-Cheney administration called "enhanced interrogation techniques"; or, in other words, torture.

Of course we are not meant to take these scenes in Splinter Cell seriously: the torturee's symbolic role is merely that of a malfunctioning vending machine, which needs to be slapped a few times with the action button so that it dispenses the appropriate informational token. And one is hardly going to weep for these characters, given the hundreds of others one mercilessly necksnaps or headshots. But it's the very fact that such "interrogation" scenes are so automatic and unproblematized that reveals how deeply the game is immersed — or, to use an appropriate buzzword about the relationship between war and the media, embedded — in national-security ideology: the proposition that, when it comes to anything that can be labelled "terrorism", any and all behaviour is not only acceptable but morally necessary.

The bin Laden boss might have been defeated, but national-security ideology is always on the lookout for a new monster. The British police now keep tabs on a category of citizens called "domestic extremists": not obsessive vacuumers and washers-up, but activists for various causes who have never committed any violent action. Videogames can surely learn from these developments to create exciting new fantasy justifications for violence. Personally, I can't wait for the game that has you "interrogate" campaigners for animal rights and gay marriage, or "kettle" a crowd of peaceful anti-cuts demonstrators. After all, you never know: they might be about to turn into zombies.

Edge 230, June 2011

Postscript, 2012: As someone on Twitter pointed out to me with alacrity, a kettling game already existed.