Mahvesh Murad is a book critic & recovering radio show host. She writes for multiple publications and hosts the Tor.com podcast Midnight in Karachi. She was born & raised in Karachi, Pakistan, where she still lives.

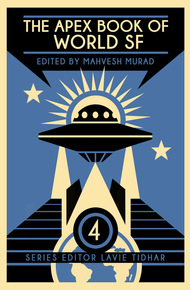

Now firmly established as the benchmark anthology series of international speculative fiction, volume 4 of The Apex Book of World SF sees debut editor Mahvesh Murad bring fresh new eyes to her selection of stories.

From Spanish steampunk and Italian horror to Nigerian science fiction and subverted Japanese folktales, from love in the time of drones to teenagers at the end of the world, the stories in this volume showcase the best of contemporary speculative fiction, wherever it's written.

Featuring Saad Hossain, JY Yang, Nene Ormes, Tang Fei, Zen Cho, Isabel Yap, and many others.

Editor Mahvesh Murad collects the latest in cutting-edge speculative fiction from around the world, including the first story from Pakistan to ever win the Bram Stoker Award, and stories from Africa, Asia, Latin America and Europe. Includes some of my favourite new writers! – Lavie Tidhar

"The fourth in a groundbreaking series highlighting international speculative fiction, ABWSF4 offers a fantastic introduction to some of the best writers alive today and encourages us to seek out more non-Anglophone works of spec fic."

– SFSignal.com, Rachel Cordasco"Different styles of storytelling, different perspectives to what you might find western speculative fiction. Some have slow reveals, others get to the point. Some are subverted, others with the typical short-story reveal at the end. There really is something for everyone. Nothing seems tired or clichéd."

– Geek Syndicate"If provoking a "sense of wonder" is one of the primary effects of the genre, there's wonder and strangeness enough in the anthology, which also manages to elude the cozy middle-class trappings of privilege that usually make "standard" science fiction so boring and predictable."

– LA Review of Books"A truly unforgettable collection, showcasing the best of speculative fiction that the world has to offer."

– Strange Horizons"The Vaporization Enthalpy of a Peculiar Pakistani Family"

Usman T. Malik

Usman T. Malik is a Pakistani writer currently living in Florida. His work has appeared in Tor.com, Nightmare, Strange Horizons, and elsewhere. The following story won the 2014 Bram Stoker Award and was nominated for a Nebula Award.

1

THE SOLID PHASE of Matter is a state wherein a substance is particulately bound. To transform a solid into liquid, the intermolecular forces need to be overcome, which may be achieved by adding energy. The energy necessary to break such bonds is, ironically, called the heat of fusion.

On a Friday after jumah prayers, under the sturdy old oak in their yard, they came together as a family for the last time. Her brother gave in and wept as Tara watched, eyes prickling with a warmth that wouldn't disperse no matter how much she knuckled them, or blinked.

"Monsters," Sohail said, his voice raspy. He wiped his mouth with the back of his hand and looked at the sky, a vast whiteness cobblestoned with heat. The plowed wheat fields beyond the steppe on which their house perched were baked and khaki and shivered a little under Tara's feet. An earthquake or a passing vehicle on the highway? Perhaps it was just foreknowledge that made her dizzy. She pulled at her lower lip and said nothing.

"Monsters," Sohail said again. "Oh God, Apee. Murderers."

She reached out and touched his shoulders. "I'm sorry." She thought he would pull back. When he didn't, she let her fingers fall and linger on the flame-shaped scar on his arm. So it begins, she thought. How many times has this happened before? Pushing and prodding us repeatedly until the night swallows us whole. She thought of that until her heart constricted with dread. "Don't do it," she said. "Don't go."

Sohail lifted his shoulders and drew his head back, watching her wonderingly as if seeing her for the first time.

"I know I ask too much," she said. "I know the customs of honor, but for the love of God let it go. One death needn't become a lodestone for others. One horror needn't—"

But he wasn't listening, she could tell. They would not hear nor see once the blood was upon them, didn't the Scriptures say so? Sohail heard, but didn't listen. His conjoined eyebrows, like dark hands held, twitched. "Her name meant 'a rose'," he said and smiled. It was beautiful, that smile, heartbreaking, frightening. "Under the mango trees by Chacha Barkat's farm Gulminay told me that, as I kissed her hand. Whispered it in my ear, her finger circling my temple. A rose blooming in the rain. Did you know that?"

Tara didn't. The sorrow of his confession filled her now as did the certainty of his leaving. "Yes," she lied, looking him in the eyes. God, his eyes looked awful: webbed with red, with thin tendrils of steam rising from them. "A rose God gave us and took away because He loved her so."

"Wasn't God," Sohail said and rubbed his fingers together. The sound was insectile. "Monsters." He turned his back to her and was able to speak rapidly, "I'm leaving tomorrow morning. I'm going to the mountains. I will take some bread and dried meat. I will stay there until I'm shown a sign, and once I am," his back arched, then straightened. He had lost weight; his shoulder blades poked through the khaddar shirt like trowels, "I will arise and go to their homes. I will go to them as God's wrath. I will—"

She cut him off, her heart pumping fear through her body like poison. "What if you go to them and die? What if you go to them like a steer to the slaughter? And Ma and I—what if months later we sit here and watch a dusty vehicle climb the hill, bouncing a sack of meat in the back seat that was once you? What if…"

But she couldn't go on giving name to her terrors. Instead, she said, "If you go, know that we as we are now will be gone forever."

He shuddered. "We were gone when she was gone. We were shattered with her bones." The wind picked up, a whipping, chador-lifting sultry gust that made Tara's flesh prickle. Sohail began to walk down the steppes, each with its own crop: tobacco, corn, rice stalks wavering in knee-high water; and as she watched his lean farmer body move away, it seemed to her as if his back was not drenched in sweat, but acid. That his flesh glistened not from moisture, but blood. All at once their world was just too much, or not enough—Tara couldn't decide which—and the weight of that unseen future weighed her down until she couldn't breathe. "My brother," she said and began to cry. "You're my little brother."

Sohail continued walking his careful, dead man's walk until his head was a wobbling black pumpkin rising from the last steppe. She watched him disappear in the undulations of her motherland, helpless to stop the fatal fracturing of her world, wondering if he would stop or doubt or look back.

Sohail never looked back.

Ma died three months later.

The village menfolk told her the death prayer was brief and moving. Tara couldn't attend because she was a woman.

They helped her bury Ma's sorrow-filled body, and the rotund mullah clucked and murmured over the fresh mound. The women embraced her and crooned and urged her to vent.

"Weep, our daughter," they cried, "for the childrens' tears of love are like manna for the departed."

Tara tried to weep and felt guilty when she couldn't. Ma had been sick and in pain for a long time and her hastened death was a mercy, but you couldn't say that out loud. Besides, the women had said children, and Sohail wasn't there. Not at the funeral, nor during the days after. Tara dared not wonder where he was, nor imagine his beautiful face gleaming in the dark atop a stony mountain, persevering in his vigil.

"What will you do now?" they asked, gathering around her with sharp, interested eyes. She knew what they really meant. A young widow with no family was a stranger amidst her clan. At best an oddity; at her worst a seductress. Tara was surprised to discover their concern didn't frighten her. The perfect loneliness of it, the inadvertent exclusion—they were just more beads in the tautening string of her life.

"I'm thinking of going to the City," she told them. "Ma has a cousin there. Perhaps he can help me with bread and board, while I look for work."

She paused, startled by a clear memory: Sohail and Gulminay by the Kunhar River, fishing for trout. Gulminay's sequined hijab dappling the stream with emerald as she reached down into the water with long, pale fingers. Sohail grinning his stupid lover's grin as his small hands encircled her waist, and Tara watched them both from the shade of the eucalyptus, fond and jealous. By then Tara's husband was long gone and she could forgive herself the occasional resentment.

She forced the memory away. "Yes, I think I might go to the City for a while." She laughed. The sound rang hollow and strange in the emptiness of her tin-and-timber house. "Who knows? I might even go back to school. I used to enjoy reading once." She smiled at these women with their hateful, sympathetic eyes that watched her cautiously as they would a rabid animal. She nodded, talking mostly to herself. "Yes, that would be good. Hashim would've wanted that."

They drew back from her, from her late husband's mention. Why not? she thought. Everything she touched fell apart; everyone around her died or went missing. There was no judgment here, just dreadful awe. She could allow them that, she thought.