Trista Payte

Trista is an overworked and underpaid adjunct lecturer living in the suburbs of Los Angeles with her partner and two children. You can find her most days at California State University, Northridge, her alma mater and her home base where she teaches Literature, Composition, and Humanities, while helping to run the on-campus writing center. When she isn't fostering and facilitating the writing of others, her own writing sometimes happens, although it is mostly done in the notes of her cell phone these days. She has been published multiple times (The Northridge Review, Chaparral, Uno Kudo, and Angel City Review to name a few) and once upon a time was featured in the Los Angeles New Short Fiction Series. Her kids are teens and they still think she is cool, which has nothing to do with her academic/writerly life, but is a pretty big achievement nonetheless.

Christian Cardenas

Christian lives in the Los Angeles environs with his beautiful wife, where he teaches English at a private middle school and high school. He constantly works to infuse film, television, comics, and video games into his ever-evolving curriculum, or really anything that'll liven up the classroom experience. Having received his BA and MA in Creative Writing from Cal State Northridge, Christian passionately explores the conversations happening in and around games. Select Start Press, launched with his pal Dylan Altman, is his dream-come-true project intended to champion evolving perspectives on video games and what they can offer as cultural texts.

Dylan Altman

Dylan is an adjunct professor at what feels like every community college and state college in Southern California: CSUN, Los Angeles Valley College, and Oxnard College. When he isn't in his car, driving from one university to another, he is playing video games, grading student papers, writing strange fiction, spending time with his wife and his dog, and trying to make the movies that he would like to watch. He is one of the co-founders of Select Start Press and is the first person to admit that the only thing that he truly knows is that he knows nothing.

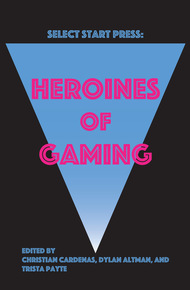

Heroines of Gaming is remarkable anthology exploring and celebrating female video game characters and their position in the gaming pantheon. Featuring a foreword by Keza MacDonald, this compelling collection of essays examines the impact that women in games have had on the lives of so many players around the world.

An entertaining compendium looking at lady heroes and protagonists in games - from Carmen Sandiego to Pokemon Crystal's Kris & far beyond. – Simon Carless

"In its second offering, Select Start Press puts forth an engaging and thought provoking collection of essays on the "Heroines of Gaming," the ways in which they embodied feminist/queer ideas, and how these characters influenced the development of the authors' sense of self and awareness of patriarchal power structures"

– Amazon Review"they have proven that video games and its culture are far more than just about passive entertainment."

"This is an excellent read for anyone looking to explore the types of roles that women have played in numerous video games and how they have impacted the authors of each of the essays."

– Amazon Review" this book addresses some rather fascinating questions regarding a sense of ownership and agency as players explore relationships between the gaming experience and leading female roles."

"It's refreshing to read about differential experiences of learning through female heroines without a mundane game review structure; and for that reason alone, I highly recommend giving this book a read."

– Amazon Review"Their love for gaming and their roles in academia pushed CSUN alumni, Dylan Altman and Christian Cardenas, to work on projects that raise the level of discourse about video games. Altman and Cardenas released their new book "Heroines of Gaming," an anthology that delves into female characters in video games and the impact on players."

– CSUN SundialStart

Keza MacDonald

Aged ten or eleven, I am wrestling with one of the most idiosyncratic control systems ever devised in an attempt to liberate Lara Croft from an icy cave, turning down the volume so that the sound of her dual-pistol gunshots won't escape the room. The original Tomb Raider (1996) is the first game I have ever managed to play that has guns; a combination of protective parents and a Nintendo-powered childhood ensured that I hadn't so much as sampled a GoldenEye (1995) deathmatch yet. But we've got a new family computer and my parents don't know that it came with a pack-in copy of Tomb Raider, already quite an old game by that point. My furtive tomb-exploration sessions with Lara felt all the more tense for the possibility of my parents walking in and discovering me playing it.

That isn't the only reason that Tomb Raider is vivid in my memory. It is the first game I can ever remember playing as someone of my own sex. I'd controlled little red plumbers, cuddly monkeys, sentient gloves, boys, bears, planes–but never an actual human woman. Sometimes as a kid, without any girls to play as, I would make them up: in my head, the Link of The Legend of Zelda: Link to the Past (1991) was either gender-swapped or genderless. Thinking back on my childhood gaming experiences, I spent a not-insignificant portion of my time projecting and pretending, and stubbornly entering my own name on RPG screens instead of going with the male default. So as I furtively made my way through the first two Tomb Raider games in the little computer cupboard off our living room, I really felt a connection with Lara Croft. I looked up to her because Lara Croft was all I had.

Inside of the game, she was an adventurer, and archaeologist, a female Indiana Jones–a badass. Outside of the game, though, as I would discover later, she was a marketing tool, a sex symbol, a big-breasted model used to lure young men into making a purchase. The version of Lara Croft that existed in the game and in my imagination did not line up with Lara Croft as she existed in suggestive adverts, Playboy spreads and, indeed, the games magazines I used to read. One line from a review of one of Croft's early adventures read, memorably, "Lara gets on our tits as much as we'd like to get on hers." By the time I got my first job in the video games industry in the mid-00s, the first female game character I had ever controlled had come to symbolise the frustrations of being a woman in that field: no matter how much of a badass you were, sometimes it felt like nobody really took you seriously.

My experience is typical of any woman who grew up playing games in the 90s. There weren't that many female characters around, and those we did have were often relentlessly sexualised in an attempt to appeal to a presumed adolescent-male "gaming demographic." Despite the slim pickings, though, we found our female characters to aspire to. Whilst I idolised Lara, the author of one of the essays in this collection, Cindy Watkins, latched onto the mysterious Carmen Sandiego, the antihero star of a whole series of infotainment games that could often be found on school computers in the 1990s by bored kids in after-school clubs. Now and then there would be an awesome female supporting character or party member in an RPG, like The Secret of Mana's (1993) Primm, who became an early example of female autonomy and self-determination for Jacob Euteneuer.

On the rare occasion that a game let us choose whether to play as a boy or a girl, it was a bit of a revelation. What seemed like a superficial choice to any boy took on enormous significance for girls starved of representation in video games. Kris, Pokémon Crystal's (2000) otherwise unmemorable female character option, was a formative gaming memory for Meg Eden, who examines in her essay how much that simple choice can mean.

Later, when we gaming girls of the 1990s grew up and became gaming women of the 2000s, we would comb through endless tropey, subtly or overtly sexist female characters in search of the odd woman we could make a case for as a positive representation–as Tina Thai does for Metal Gear Solid's Meryl Silverburgh in this volume. Throughout the 2000s, game developers responded to audience demands to include more interesting female characters (because–guess what?–gaming's audience actually isn't exclusively or even predominantly adolescent and male, and a lot of data suggests that it never had been). Unfortunately, this second wave of female game characters fell foul of sexist tropes as often as they escaped them. Mounawar Abbouchi uses Dragon Age's Morrigan as an example, a character who though personable, interestingly-written, and powerful, ends up as a victim of her female body. Often, defending video games from a female, let alone feminist, perspective felt like we were tying ourselves in knots. But hey, at least we had something to argue about.

Thankfully, girls today have a much wider palate of heroines to choose from. Most games for younger players feature wide arrays of playful and playable characters, be they boy, girl, or fantasy monster. Indeed, technology now allows you to create and customize a character however you might want; to quote Dark Souls' character creation screen, "gender has no bearing on ability." My daughters won't have to do the projecting and pretending that I had to do; they won't have to think of Link as female, because Zelda herself has evolved from damsel into capable and interesting heroine in her own right, as Shay Leiss explores in the final essay of this collection. I've gotta say, I'm quite jealous.

This mirrors a general shift toward better and more prominent representation of girls and women in pop culture, from comic books to TV and movies. I might have had Mulan and Buffy the Vampire Slayer, but girls now get Moana, Wonder Woman, and the Lumberjanes. Now and then, modern games are actually better at female characters than the older comics and movies that inform them, as Jordan Puga argues in reference to Batman: Arkham Knight's (2015) portrayal of Barbara Gordon.

Teenagers, meanwhile, have even more to enjoy. I was blown away by The Last of Us: Left Behind in 2014, because it was the first real-feeling, relatable depiction friendship between girls I'd ever seen in a game. It was followed the very next year by Life is Strange, starring Max and Chloe, whose arrestingly intense relationship reminded me so strongly of the experience of being a teenage girl that I called my mother to apologize.

And as a grown woman in 2017, I too now have more interesting women to get to know, like Uncharted's Chloe Frazer and Nadine Ross, or the Dishonored franchise's Emily Kaldwin, profiled here by Sarah Zaidan. A lot of the time, these women are sharing the spotlight with a leading male–Ellie has Joel, Evie Frye has Jacob Frye, Emily Kaldwin has Corvo–but they are, finally, participating fully in games' stories and adventures, rather than being almost exclusively relegated to supporting from the sidelines. Games have also started allowing for non-binary and queer expressions and explorations of gender, as Brandon L. Sichling of the Fire Emblem essay points out–a fascinating subject that could fill a whole other book of essays.

Over the years we've heard every imaginable excuse and justification for not including female playable characters in games. Data has slowly broken down most of those arguments, many of which were nonsense in the first place. Games are mostly played by men, so games starring women just won't sell: nonsense. Animating or writing women is somehow harder than doing so for men: nonsense. Usually, including two playable character models rather than one involves effort and expense on the part of game developers, but increasingly they are willing to put in that effort. Not every modern game features prominent women, but hey, nobody was ever asking for every game to feature prominent women. All we were ever asking for was for more than two or three games a year to give us the option.

This has, finally, happened now. From my perspective, games have come a long way since I was a child. Anyone who doubts the importance of including these female characters in video games need only look at how positively girls and young women respond to them. And yet, in some areas of the gaming business there is still residual reluctance to accept girls and women as part of the club–and, unfortunately, from a small but particularly vocal segment of gamers who seem to feel greatly threatened by the presence of women players and female characters in their treehouse.

To those stubborn relics, I say: sorry, dude, but we're here now, and we're not going away. Actually, we've always been here, playing games and thinking about them, which is why more and more women are making their way into video games development and criticism, creating and commentating upon the diverse, interesting new female characters that are appearing in our games. We're nowhere near gender parity in the video games industry workforce, but greater diversity amongst developers and critics has already given us more interesting characters to get to know. That trend will only continue.