Dayna Ingram received her MFA from San Francisco State University and her BA in Creative Writing from Antioch College. Originally from Cincinnati, OH, she currently lives in Northern Kentucky with her wife and son. They are owned by three dogs and six cats. When she isn't writing or working her day job, Dayna enjoys short-distance running, long-distance reading and mid-distance Netflix binges. She is currently seeking agency representation for her dark fairy tale LITTLE DAUGHTER.

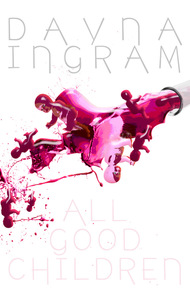

ALL GOOD CHILDREN was a finalist for the 2017 Lambda Literary Award, and was named one of 2016's Best Books by Publishers Weekly (Science Fiction category) and Kirkus Reviews Indie (YA category).

Everyone tells 14-year-old Jordan Fontaine not to worry about the summer camp that isn't really a summer camp, not to worry about the survival statistics she's been calculating since elementary school, or about the quickly averted eyes and frowning mouths of her peers when she tells them her Liaison is coming to visit her family. She does not dare to tell anyone that her pulse quickens when she looks at the beautiful Liaison. But the Liaison, whose role is to supply their inhuman masters with bodies, is being manipulated by another. And Jordan will be drawn into a dangerous coup of which she is unaware. This is a world where women are bred like cattle, ensuring the continuation of the human race—or, as they are known to the malevolent Over, sustenance. Perhaps some children need to be seen and heard.

Ingram's deadly dystopic future, in which Earth have been brought under the control of the buzzard-like Over, is all the more chilling for the ways most people lead relatively untouched lives. But a few people must pay the price for this safety, and it's never quite clear who will be chosen, or why. I loved Jordan, the rebellious daughter, sullen and complicated and so very real, but I also loved that her mother is given a voice, and an arc of her own. – Melissa Scott

"Ingram uses this beautifully written novel to bring Jordan and her family's fears to life—separation, the possibility of aliens taking over the world, and the frightening but enticing idea of a revolution. This new and invigorating addition to the YA category spotlights the bond of family and explores women's rights."

– School Library Journal"Ingram has invigorated the apocalyptic genre with a tightly woven story brimming with atmosphere. This novel is at once refreshing and thoughtful, and a great addition to the genre." -

– Publishers Weekly (starred review)"The atmosphere of adolescent angst develops around fraught conversations, from Jordan's anguished exchanges with her parents to her sullen mouthing off in group therapy; the result feels like a mashup of The Hunger Games, "The Lottery," Girl, Interrupted, and Auschwitz, with malevolent buzzards thrown in. Ingram gives her story a realism and emotional depth that make the reader care about her protagonist's fate."

– Kirkus Reviews (starred review)Prologue – Twenty-Six Years Earlier

Through the bars on his kitchen window, Dominick Silamo watches Pretoria's greatest suburb burn. It is a large window and the house is built into the hillside; he can see the whole of the downtown shopping center and the roadblocks trailing off into the smoke-filled horizon. Molotovs and pipe bombs have exploded shops and houses, cars and military vehicles. The smoke is dark and fathomless, and somewhere deep inside it creatures beat their wings like izulu, hunting. Although mythology insists fire is the only means of destroying izulu, the impossible birds-of-prey defy this, swooping and diving through the smoke as the fire consumes all that lies below them.

Silamo rinses his hands in the sink. He just had this faucet installed two months ago; stainless steel and modern, a symbol of the type of household his family would create here. The faucet handles are diamond-shaped cut glass. The refrigerator is new, too, and the cabinets are refinished, polished mahogany. Marble countertops were meant to be installed next week. He hadn't decided about the kitchen floorboards yet; they are scuffed and splintering in loose spots near the table. He was waiting until next week to look at tile samples for possible replacement.

The fires haven't yet reached the hillside; the small cul-de-sac is safe from them for now. The street has not, however, been able to avoid looters and opportunists. He hears alarms sounding off in his neighbors' identical two-story houses. No one has tried to break into his home. He is the chief of police. Things will have to grow a little more dire before they dare to explore his place.

He cannot think—does not want to think—how things could grow more dire. There are izulu in the air, straight out of storybooks and into their city, perhaps not summoning bolts of lightning but still as deadly. They swoop down into the streets and skewer citizens with their talons, lifting them up and up and up and then dropping them down and down and down. Bullets do not stop them; they are indifferent to bullets. No one has gotten close enough to try a knife, least of all him. Some folklore enthusiast thought of fire, and now here is Silamo, sweating in his unfinished kitchen, taking a break from packing the last of his bags.

Silamo selects a mug from the rack above the window and fills it with water. His gulps are greedy and loud. He wipes his forehead with the back of his wrist. Though the fires seem confined to the commercial centers, the heat has risen with the ash-black smoke. Silamo has stripped to a white sleeveless undershirt, nearly translucent with his sweat, and porous cotton slacks cinched with a plain belt. In his front pocket he carries his badge and identification, a small roll of large bills and his wedding band. In the living room next to the couch are three duffel bags filled primarily with underwear and socks, a bit more money, a compass and a road map of South Africa. The keys to his Jeep are on the table by the front door. He is almost ready to go but he must do this one last thing.

He saw them coming up the abandoned street while packing the final duffel bag upstairs. The Lieutenant General of the National Defense Force and two of the izulu. Just walking, strolling even, slow and steady strides with the smoke curling like a beckoning finger behind them. Lieutenant General Zuma led the way; the creatures kept pace behind him. Silamo's heart stopped then sped up. As they drew closer, he found himself studying the lieutenant general's uniform: pressed olive green suit adorned with silver and red military medals that gleamed in the sun; stiff octagon of a hat stamped snug over a sweating forehead. The suit was fitted, it moved with Zuma's body, sighed when he sighed, tensed when he tensed, sweated when he sweated. Silamo couldn't process it. He needed a drink of water.

There is a knock on the door. They actually knock. Silamo stands in his kitchen, mug of water in one hand, the other pressed against his fleshy stomach. He wonders what will happen if he pretends not to be home, but they must know already he is here or they would not have walked all this way. He sets the mug on the lip of the counter and moves for the other room but the mug has been precariously placed and it topples. As he exits the kitchen, he hears it thud and crack simultaneously against the floorboards, and he reflexively issues a stern hiss—"Shh!"

Silamo places both palms against the heavy front door, whispers a quick prayer, pulls back the bolt locks and opens the door.

The izulu enter first.

They tower over him, a man his mother always lovingly referred to as a giant, her little giant. They tower over him and make him feel like a child again, plaintive cries for his mommy tickling the back of his throat. Nine feet maybe, they have to duck under the doorframe and hunch slightly so as not to graze the ceiling. Their faces are the most striking, bald as they are against the coarse feathers that sheathe their bodies. The skin is pale and appears riddled with gooseflesh, something you want to touch but don't want to touch. It crinkles around the eyes and smoothes around the protrusion of the beak. These two have similar but different beaks, and Silamo wonders, while he can still muster enough unclouded thought to wonder, if the beaks of all izulu are different. The one on the left is serrated along its under edge and pointed at the tip, its nostrils placed about halfway down the shaft. The one on the right is sharp-edged but smooth with a tip that hooks downward. The color of the left is as peach pale as the bald head, the color of the right melds from pale to coal black at its hooked end. Their eyes are different too, though Silamo doesn't linger too long on them; the left's are red, the right's are a jaundiced yellow.

They push through the doorframe and Silamo backs up into the living room, ankles nudging his wife's old knitting rocker. He watches them walk into the space, an awkward shuffle on their taloned feet, so unused to such movements. What they really want to do is fly. What they really want to do is pierce his shoulders with those talons and lift him into the skies and fly and fly and fly until he grows too heavy. But what they do inside his home is shuffle to either side of the living room's arched threshold and turn their disturbing faces toward Lt. Gen. Zuma.

Zuma walks between the sentries with his hands clasped casually behind his back, his dark face filled with a toothy grin. His own eyes are rheumy with age, the green irises once vibrant, faded after forty years of military service. He has seen so much, Silamo knows; a hero as Silamo himself was growing up, yearning for someone to emulate. Silamo recalls meeting him for the first time at a fundraising event four years ago, the summer he became Chief of Police. He was so struck by the upright brilliance of the man then—how straight and tall he stood, even so close to retirement age; how magnificently he smiled, with his entire face, at each guest and shook every hand—that only after several liters of strong beer could Silamo even approach him. He remembers looking into the old lieutenant general's eyes and being jealous of the wisdom reflected in them; now all he sees in the man's eyes is a cool denial and a willingness to forget.

"Chief Silamo. I trust we have not come at a bad time."

Standing between the izulu, the living room becomes small, suffocating. Silamo feels his throat closing around the acrid meat-rot stench of the beasts. "Little bit, actually," he says. "Little bit of one, yes."

The lieutenant general's grin stretches his jaw line as he laughs. "Forgive me, then. This interruption won't last long. I am correct in assuming you are still active chief of police here, yes?"

The izulu to Zuma's left unfurls a hand from its folded wing and scratches its hooked beak. Silamo has seen these hands; surprised at first, yes, because the carrion-eaters these creatures so closely resemble in body do not possess hands, but the izulu they are at heart, of course, do. The skin is leathery and pale, like their faces, rippled like faded scar tissue; their wings seem stitched into the arms, he can see where these stitches begin and then are obscured by the dark feathers. Unlike the three-pronged talons of their feet, their hands are small and five-pronged, like fingers, though they are also talons. In the center of the hand—the palm—something crimson stains the paleness but Silamo can't see it clearly. The tip of what would be the izulu's index finger scratches at its beak, then disappears beneath its wing with a sound like a tent-flap closing.

Silamo remembers when he was last active as police chief, his first tactical maneuver when this all began, three weeks ago: to evacuate downtown Pretoria, primarily the university and administrative district, which were being hit the hardest with what early reports claimed were guerrilla attacks of unknown origin. Civilian witnesses swore to seeing bombs dropped, non-exploding bombs, they said, or silent exploders: one second a dark streak through the sky, soundless, and the next a body on the steps of the courthouse, or what was once a body, all the things that made it a body now splattered outside of it in a bloody sea. Silamo assembled a team and went in with his lofty goals of establishing perimeters, setting up road checks, rushing the injured to waiting mobile medical units. There were no injured, of course; the izulu left no injured.

The SANDF were still mobilizing air-strike units, so until then all Silamo was meant to do was get the civilians to safety and attempt to positively identify the bombers, the shooters, whomever. As the carnage seemed localized at the university, Silamo moved in on the campus with a small contingent of officers. They swept the place, clearing out students who had taken refuge under desks and inside closets, staff who had barricaded themselves in their offices with ineffectually stacked waste bins and orthopedic roller chairs. There was no damage inside the buildings, no terrorist waiting with bombs or guns. The remnants of the attack were smeared along the main building's steps, the sidewalk, the streets for three blocks in every direction. Bodies moldering in the afternoon sun, attracting flies and rodents with the collective allure of decay.

His officers met no resistance inside the university nor throughout their respective sweeps of the three-square-block radius. Silamo made the call to load up the civilians and take them out of the strike zone. He was ready to report to the SANDF that there would be no need for an air unit; whoever had perpetuated these attacks was gone now, damage done. Van doors slammed closed around him as he stood next to his vehicle, trying not to look at the bodies in the streets, or to breathe too deeply through his nose. He would have to call in a cleaner, and of course the coroner would have to examine what was left of the bodies, to determine cause of death. What sorts of bombs were these? What sort of people launched an attack in this manner?

He waited beside his vehicle while the others evacuated, smoking a cigarette. His wife was always trying to get him to quit, for Heaven's sake. He felt the things he'd seen today warranted at least one cigarette, maybe two.

As he opened the car door and stamped out the cigarette stub, he caught movement in the shadows of a bank across the street. He waited a moment, squinting into the darkness of the alley. There, he saw it again. His hand moved to the pistol at his waist, and he closed his door and started across the street. From behind him, a woman's voice shouted, "Help me!"

He turned and saw a slender woman crawling on her elbows from beneath a truck parked four cars down from his. She appeared unhurt but she was shaking badly and her face was red and puffy from crying, her hair and light blue pantsuit dirty from having hidden under the truck for so long.

"You, there!" He called to her. She was trying to stand up, using the truck to brace herself, continuing to shout for help. He strode toward her, saying, "I'm here. I'll help you."

One second it was not there, and the next it was. It was on her in a blink; he could not even say if he had blinked, but there it was, like an apparition. She was stooped, her hands groping the hood of the truck as she struggled to stand. Then the talons were in her, stabbing just beneath the shoulder blades. The massive thing was something Silamo was unable to comprehend; six feet away from it and he couldn't describe it as anything other than the mythological izulu, though it was a vulture, a mutated bird of prey, as he would later tell it, and a devil, a demon, a bad dream.

It could have disappeared with the woman as quickly as it appeared on top of her, but it lingered. It pushed its wings against the air and pulled her from the truck, from the safety of the ground. Silamo felt the wind move around him with the movement of the thing's wings, a span that doubled its size. It hovered over the truck, looking down at Silamo; Silamo was certain it looked down at him. Its orange eyes saw him. It beat its wings slowly, purposefully, and it let the woman in its grasp squirm and scream, and it made no sound, no sound but the wind. It was Christ-like, Silamo will remember thinking later: the spread of its wings, the sun glaring behind it, its extreme calm and severe intention as it hovered there, seeing Silamo, making sure Silamo saw it.

Another non-blink and it was gone. Only then did Silamo bring up his pistol. Only then could he move; only then could he feel the warm trickle of urine down his thigh.

That was three weeks ago. He knew he should have died. The thing should have grabbed him. It let him live, which frightened him. Because it was purposeful, calculating. They wanted him to know they were back so that he could report it to the SANDF. A civilian, a mass of civilians, could be discredited, ignored, accused of madness or attempting to incite panic. But he was chief of police. Someone would listen to him. Someone important would listen, and they would know: the izulu had declared another war.

Back in the house, Lt. Gen. Zuma's bemused remark pulls Silamo into the present: "My apologies if the question is too difficult."

Silamo's chest aches with the breath he only just now realizes he has yet to release. Painfully, he exhales. Forcing himself to look at Zuma, he concedes, "Yes, I'm still the chief. What can I do for you?"

"How about a cup of tea?"

"Yes. Yes, of course. All right."

Silamo steps backwards through the kitchen archway, and Zuma finally catches on. "Oh my," he says, "I forgot. Do they bother you that much? Very well, they'll stay here."

The izulu remain as sentries in the living room while Zuma follows Silamo—who still does not turn his back on the lieutenant general—into the kitchen. Zuma's boots click across the hardwood. Silamo remembers himself enough to pull out a chair for him. His own heel knocks into the dropped mug and crunches the chipped-off ceramic handle.

Zuma looks down, then back up, that disarming smile still stitched on. "Not too careful today, are we?"

The back of Silamo's neck begins to sweat. He attempts to smile but then drops it. Bending down to retrieve the ceramic pieces, he says, "My mind has been on other things."

Zuma sits at the corner of the table, resting his hands, wrist over wrist, across the top, and crossing his right leg over his left thigh. His back is straight, his eyes steady, his smile constant. He does not remove his hat. His eyes shift over Silamo's shoulder and he points a lazy finger. "Incredible view."

Silamo places the mug shards in the sink and looks out the same window. The smoke has thickened and is rising higher. Sounds from the street are rising too: screams and cries, angry shouts, car alarms, things breaking. The smell of sulfur is beginning to seep into the house as well. Fire and brimstone, Silamo thinks. He feels uneasy with his back to Zuma so he grabs two fresh mugs and turns around.

"What type of tea, then?"

It seems the most absurd question anyone could ask in the midst of a war, but if Zuma insists on these sorts of pleasantries, Silamo is determined to play along.

"Rooibos. Always been my favorite. You have it?"

Zuma's eyes, and his smile, never leave Silamo as he fills the kettle with water and starts the gas burners. He places two tea bags in the mugs, pulls out a chair for himself across the table from Zuma and sits. He is careful to keep his hands on the tabletop so the lieutenant general can see he has no secrets. If he turns his head even slightly to the left he can see both izulu through the archway. He focuses on Zuma.

"I stopped by headquarters before coming here," Zuma says. "It's completely barricaded. Are there officers inside?"

"Some. It was their choice. Others I've sent to Jozi to assist with military operations. As per your orders."

"Going to ground." Zuma shakes his head. The lip of his hat shadows his eyes. "Unwise. Do they think to wait it out, as if this were a common storm?"

"There do not seem to be many wise decisions left to us, Lieutenant General."

"You are right. What can we do? Fight. Flight. Those are the rock and the hard place, as far as I see it. Neither offers salvation. Strange no one has yet chosen surrender."

"Strange?" Silamo folds his fingers together so as not to make fists. His knuckles whiten with the strain. "You would have us surrender? What does that mean to them, other than death?"

"What does it mean to whom?"

"Them." His eyes flick left without seeing much more than amorphous shadows. "The izulu."

Zuma's eyes linger on the creatures before turning back to Silamo. His smile appears even more bemused. "Izulu, you say? That's delightful. Our people have many names for them. Demon is most common. When they first rose—what was it? twenty years ago?—the popular term was vampire, which is closer. Vulture, of course, works best as far as resemblance. I think it's regional, the names. Certain ones stick better than others. I must admit 'izulu' is new to me."

Silamo struggles for a nonchalant shrug. "What do you call them?"

"They prefer to be called 'the Over.' It derives from Nietzsche's übermensch. Over men. You've heard of this? They have a mild preoccupation with our human philosophies." Zuma chuckles.

Silamo has trouble catching a breath long enough to ask, "How do you know this?" When Zuma only smiles into the question, Silamo suggests, naïvely—but, god, how he longs to be naïve—"Do you control them?"

Zuma outright laughs; his mouth opens and his shoulders move with the boisterous sound, but his eyes remain steady and fixed on Silamo. It makes the hairs along Silamo's arms stand up.

The laugh is cut off by the sharp cry of the tea kettle. Zuma says, "I'm quite parched."

Silamo makes no move to get up from the table. He is afraid his muscles will prove too weak for the task. He wipes sweat from his brows with his fingers, and slides his hands into his lap under the table.

"Allow me," Zuma says.

He rises and goes to the stove. Silamo listens to him pour the tea and open the tins on the counter, searching for sugar cubes. The lieutenant general begins to whistle. A light smell of herbal sweetness fills the room.

Zuma places a steaming mug in front of Silamo and retakes his seat at the other end of the table. He stops whistling and sips from the mug, making a satisfied sound as he puts the mug back down.

In the silence, something large and nearby explodes outside. Neither man flinches; they are staring at each other. One of the house's old floorboards begins to moan, and Silamo says, "So you have surrendered."

"You misunderstand," Zuma says. "I have not given up; I've defected. And you will, too, by the end of this conversation."

While Zuma talks, Silamo eases a small blade out of its sheath on the underside of his belt. He holds it against his thigh. "Convince me, then."

Finally, Zuma abandons his false smile. "You know this is not a war, don't you? You have always been a smart man, a prudent man. Pretoria, Jozi, the whole of Gauteng—this isn't even a battle, not to them. It's practice, a rehearsal; it's training, it's recruitment, it's preparation for the Big Show. Not far off, that. You know what Australia was? A failsafe. They'll always have Australia. That sounds like a song, doesn't it? Is it a song?"

Silamo's sweat runs cold along his skin. Suddenly, he feels calm. Zuma is insane, he thinks. An insane man who has given up. A man of high rank, which makes things difficult. But not lost.

"Perhaps a movie," Silamo says.

Zuma slaps his palm on the table, shaking the mugs a little. "A movie! That's what we're missing. That is something that would take the fear out of it, isn't it? To memorialize in film the colossal failure that was the War for Australia. The entire continent a nuclear wasteland, unfit for human habitation. Exactly how the Over planned it."

"You seem excited."

"That's a side effect of the mind control." Zuma twists his back toward Silamo, and Silamo's arm goes rigid, his fist tightening around the blade. But then Zuma removes his hat and bends his head forward enough for Silamo to see the large hole at the base of his neck. A glossy membranous film covers the wound's two-inch diameter, the skin around it an irritated pink. Silamo's mouth slacks open and he has to work hard to close it.

Zuma twists back around. "How does it look? I haven't seen it myself. It's a mite fresh."

Silamo struggles to work up saliva. "You let them do this to you? I would have died. I would have fought them. I would have died fighting them."

"Is that why you packed those three bags at the door?" Zuma's smile returns. "Full of weapons with which to fight your enemy? I know you are running, and that is smart, Chief Silamo. In fact, I want you to run. The Over want you to run. But they would prefer if you took a select group of citizens with you."

"I'll do nothing for them."

"Will you listen? Listen to yourself. Only when backed into a wall do you find your strength, your bravery. I'm hefting you over that wall. I'm giving you the tools to—"

"—to be mind-fucked?"

"—to climb over. Mind-fucked? You're killing me, Silamo. May I call you Dominick? Formalities seem silly at this point, do they not?" Zuma sips at his tea again, although by this time it has cooled enough to gulp. "I misspoke. Mind control isn't exactly correct. I admit, I wanted to shock you. I see it worked. But no, it's not that exactly, it's…a pathway. A communications link. This way, they can speak to me. I can know them, the way only a handful of us are beginning to know them. It's, well, it's a form of trust. They trust me. They trust me to be their Liaison, to begin negotiations of their treaty."

"I don't believe this."

"No need to take it on faith, dear Dominick. They'll be more than happy to show you. They've already shown me so much. They've shown me the future, Dominick, and it certainly isn't here. No, we must sacrifice our holdings here, for the survival of our species. That's what they're offering us, after all, survival. Not only that, but—listen, the treaty will be signed, I've no doubts. Our president has already signed it. All the leaders will. And when we explain it—you and I and all the other Liaisons—to the citizens, the world will understand. They'll see it is not so great a sacrifice, the things the Over ask of us. A few will die, certainly, but look out your window, Dominick—look at the city burning, the people burning it. Can we survive much more of this? Can we?

"I know you have a knife on you."

Silamo plays Zuma's bluff. "Yeah, and a sharp shooter outside with you in his sights. I have nothing, Zuma. I have nothing."

"The Over tell me it's clutched in your right hand, and when I turned my back to you a moment ago, you nearly raised it to throw at my neck. Let's not play games anymore, Dominick, shall we?"

"Do not use my name," Silamo growls. He brings the knife up to the table and rests his knuckles against the edge. "I'll kill myself before I let them take me."

"Don't be so dramatic." Zuma laughs and throws up his arms, shaking his head at nothing. He fits his hat back onto his head, looks into the living room and hooks a thumb at Silamo. "This guy." He looks back at Silamo. "Are you shaking? I am trying to tell you, Chief Silamo, that there is no need for shaking. No need for fear. Listen. All I need for you to do is evacuate the people on this list." From his breast pocket, he produces two sheets of folded paper and slides them across the table to Silamo, who does not reach for them. "You'll have to take them to Jozi and use the rivers to the Indian Ocean. There'll be a naval ship waiting at Durban. The Over will not attack you; it's not them I'm worried about. But our citizens are panicking. They no longer fear our human consequences, if ever they truly did.

"The names on this list, these men and women are important. They're vital to the Over's treaty negotiations. Failure of this mission is not an option. That is why you need to be made a Liaison, Silamo. Total trust."

"I think you had it right, Zuma. It is mind control. A touch of madness hasn't helped your case so much either. No man with any honor would strike a deal with demons."

"It's a good deal," Zuma says. "Ninety percent of the world's current population will be spared. And that's a worst-case scenario—if the negotiations take longer than expected, if certain world leaders try their nukes again, or chemical warfare. But with full cooperation, we may only lose one or two percent. A token number, in the grand scheme. As I said, they've shown me the future. It's a controlled future, certainly, but it allows us to keep many of our familiar freedoms. It isn't communism. There will be systems in place so the Over will get what they need, and what they need is us. Humans. We are life to them. Life. Let me show you."

Zuma rises once again, and Silamo rises with him, knocking his chair back in his haste. He presses the edge of the blade to his throat and says again, "I'll kill myself. I want no part of them. I'll kill myself, I swear it."

"Dominick" Zuma frowns, and for a moment his eyes appear genuinely sad. "You disappoint me. Very well. If you cannot find it in your heart to care about the billions of lives you will save by joining the Over, I think you can find some compassion for your wife and daughter."

"They're dead," Silamo says. "They died in one of the first riots. There is nothing you can threaten me with, Zuma. My only choice is death now."

"Die now." Zuma picks up the list of names and holds it out to Silamo. "Or die later. Die a coward or a hero. The people on this list are counting on you. You are their salvation. Surely you can sacrifice your own life for something greater than spite?"

Silamo's eyes blink to the izulu—the Over—standing in the living room. They haven't moved, but their heads are tilted identically, as if they are listening though they have no ears. The floorboards creak again.

Silamo lowers the knife and sets it on the table. He takes the list of names from Zuma. "All right. I'll do it. This one last mission. Only…only not here. The fires, the bombs, they're getting closer. We'll go somewhere safer. Then I'll do it."

Zuma clamps a heavy hand on Silamo's damp shoulder. Silamo fails to turn his grimace into a smile, but Zuma smiles wide enough for both of them. "Good man," he says. He stretches an arm out in front of them. "After you."

Silamo's body tenses as he walks beneath the archway into the living room. The sentries watch him; his mind flashes a memory of watching a movie with his daughter only—what? last summer? earlier? In it, a young boy on a quest must pass through a guard of giant golden sphinxes, whose eyes are closed. As he walks, their eyes open and they fire lasers at him. He makes it through, but only just. Silamo closes his own eyes as he walks past the izulu; if they do laser him to death, he prefers not to see it coming.

He doesn't open his eyes until his foot bumps into one of the duffel bags. He looks down at it. No need for it now, not for him. He stuffs two fingers into his pocket and fishes out his wedding band. He drops it onto the duffel bag as he moves to the front door.

Outside, the wind has picked up and the world feels as if it exists inside an oven. Everything is closer, pressing in: the shouting, the crying, the breaking, the burning. Maybe Zuma, despite his insanity, does have a point. If the treaty can stop this violence, can save billions, as Zuma claims it can, maybe it is worth it. Maybe it is worth giving up the world.

Zuma walks out of the house, closing the door behind him. He adjusts his hat to best shield his eyes from the glare of the sun, straightens his unruffled shirt front, and marches to Silamo's side. "A car is waiting for us at the bottom of the hill, if it hasn't been bombed yet." His white teeth burn through Silamo. "Shall we?"

"The Over." Silamo looks back at the house. "Aren't they coming?"

"Oh my, I thought I'd explained clearly. Being a Liaison to the Over requires total trust. You broke that before you even began. They couldn't just let that slide. It wouldn't be fair."

From inside the house, a child's scream rips open Silamo's gut. He shouts for her, "Heaven!"

The heel of Zuma's hand crashes into Silamo's nose. The world blinks out and gravity rushes away from him. Pressure mounts inside his head, and he is squinting at the sky, the sun an evil eye burning out his sins. Zuma's dark head bends into his field of vision. He can feel the blood streaming from his nose into his mouth, down the back of his dry throat. He can hear his wife crying, and the sound of something else, some vital thing being pulled apart.

"Pity," Zuma says, a drop of spittle falling onto Silamo's eyelid. "You were my first choice for this mission. Remember that god awful charity gala? We had some laughs. I had hoped to spare you. Well." Zuma lifts his heavy boot above Silamo's face. "I'll find someone else."