Melissa Scott is from Little Rock, Arkansas, and studied history at Harvard College and Brandeis University, where she earned her PhD in the Comparative History program. She is the author of more than thirty original science fiction and fantasy novels, most with queer themes and characters, as well as authorized tie-ins for Star Trek: DS9, Star Trek: Voyager, Stargate SG-1, Stargate Atlantis, and Star Wars Rebels. She won Lambda Literary Awards for Trouble and Her Friends, Shadow Man, Point of Dreams (written with her late partner, Lisa A. Barnett), and Death by Silver, written with Amy Griswold. She also won Spectrum Awards for Shadow Man, Fairs' Point, Death By Silver, and for the short story "The Rocky Side of the Sky" (Periphery, Lethe Press) as well as the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer. She was also shortlisted for the Otherwise (Tiptree) Award and the Midwest Book Awards. Her latest short story, "Sirens," appeared in the collection Retellings of the Inland Seas, and her text-based game for Choice of Games, A Player's Heart, came out in 2020. Her solo novels, The Master of Samar (2023) and Fallen (2023) are both available from Candlemark & Gleam.

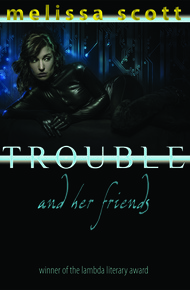

Only a little while from now, the forces of law and order cracked down on the virtual world. India Carless, alias Trouble, saw the end coming, and slipped away, retiring from the hacker's life to run a small network for an artist's co-op. Now someone calling themself "Trouble" has returned to thenets, and the real Trouble has no choice but to deal with them herself, before she's dragged back into the criminal life she thought she'd left behind. Once the fastest gun on the electronic frontier, she's faced with one last fight. And it's a killer.

The title and the ending of this novel coalesced as I walked the dog around a tidal mill pond, and for all the glitter of the nets, the story is grounded in the steely chill of the New England coast in spring just before the world turns green again. And I think that's fitting: this novel is as much about not being able to escape the physical world as it is about the excitements of the virtual, and about turning that perceived disadvantage into a source of strength. I think that theme, as much as the queer characters and community that dominate the story, is what makes this one of my queerest books. – Melissa Scott

"Both excellent and thought-provoking"

– Analog"Provocative, well written, and thoroughly entertaining, Trouble and Her Friends marks a new high in Melissa Scott's impressive career."

– Philadelphia Inquirer"Scott's talent as a storyteller continues to grow, as evidenced by her sizzling prose and carefully balanced plotting."

– Library Journal"Scott's best work: vivid, fast-moving, and startlingly erotic."

– Nicola Griffith, winner of the James Tiptree, Jr. AwardIt was very quiet in the apartment, too quiet, just the distant sound of wind and the occasional rattle of the fire escape in the other room. Cerise winced, and reached for the main remote, jabbed at the buttons until the media center lit. Trouble had left the main screen tuned to the news channel, and the blare of the announcer's voice filled the room.

"—top story, the Senate today voted to override the presidential veto of the Evans-Tindale Bill, joining the House in handing the president a resounding defeat. Marjorie Albuez in Washington has more on the story."

"Thank you, Jim. By accepting the compromise bill sponsored by Charles Evans and Alexander Tindale, Congress today seems to have ensured that the United States will remain the only industrial nation that is not a signatory to the Amsterdam Network Conventions."

The voice droned on, but Cerise was no longer listening. She swung back to face the linked computers, the remaining files forgotten, and reached for the dollie-cord snugged into its housing at the base of the dedicated brainbox. She tiled her head to fit the cord into the dollie-slot behind her right ear, but did not launch herself directly onto the nets. This was why Trouble had left. She had been talking for months about what would happen if the U.S. rejected the Amsterdam Conventions, about how even the supposedly benign Evans-Tindale Bill would destroy the cracker community, bringing them all finally under an alien, ill-conceived, ill-fitting law. For a moment, Cerise almost believed those prophecies of doom. No one had believed that Congress would buy Evans-Tindale, it bore no relation to virtuality—

"—completes what the so-called Nunberg Act—the Industrial Espionage Act, as it is more properly known—attempted to provide two years ago." That was a new voice, but Cerise didn't turn to identify the speaker. "The Evans-Tindale Bill codified the various provisions of the Nunberg Act, and creates a new entity within the Treasury Department that will have law enforcement responsibility on the nets, replacing the patchwork system currently in place. In a nutshell, Evans-Tindale, like the Nunberg Act before it, redefines so-called cyberspace as a particular legal jurisdiction, and establishes a code of law governing these electronic transactions."

Which means, Cerise thought, that we're all screwed. She sat for a long moment, staring at her screen, at the distorted image displayed in its central window. That map no longer mattered, because now there was no reason to keep those secrets, at least not in the legal world of the bright lights: there was a new law out there, and one that could be enforced in the real world. And for the shadows—the illegal world of crackers and grey- and black-market dealers, the world where she had lived ever since she'd run away from her home, her true name, and the secretarial school that had been her second home—it meant the end of an era. It would no longer be possible to dodge the law in one jurisdiction by claiming that you, or your machines, or your target, were located elsewhere; it would no longer be possible to argue that there was no theft where there was no real property. All that had been decided, and by fiat, not the nets' own powerful consensus. And Evans-Tindale also meant that there was no longer any possibility of legalizing the brainworm. The old-style crackers and the legal netwalkers had proclaimed their innocence by blaming everything on the brainworm and its users, and no one in authority seemed to know enough to know that they were lying.

She reached for the safety, cupped it in her left hand, hesitated, and wound the cord twice around her wrist, just in case. If she pressed that button, or its virtual analogue, the system would shut down instantly and automatically, dumping her back in the safety of her own home system, her own body. She took a deep breath, fighting back despair, and used her right hand to touch the sequence that opened a net gateway. The brainworm responded perfectly, its impulses overriding the merely physical input of the apartment, and she flung herself out into the glittering perpetual night that was the net.

Alice in Wonderland, Alice down the rabbit hole, Alice out in cyberspace, flung along the lines of data, flying across fields of light, the night cities that live only behind her eyes. Power rides her fingers, she moves from datashell to datashell, walking the nets like the ghost of a shadow, her trail vanishing behind her as she goes. She carries power in the dark behind her eyes.

And she needs it, tonight, in the chaos that whirls between the islands of the corporate spaces, their boundaries marked by heaps and new whorls of glittering IC(E).The bulletin boards, the great sink of the BBS where all the lines of data eventually meet and merge and pool into a sink of slow transfer, limited nodes, and low-budget users, are in upheaval. The familiar icons and signpost-symbols that guide the unwary are cone completely, erased by their owners or remade in new and somehow threatening form. Icons whirl past her, some representing people she knows, has worked with. She smells fear sharp as sweat, hears the constant rustling murmur of the transactions that surround her as the brainworm translates what is truly only electrons, data transferred from computer to computer, to sensation in her brain. She glimpses a familiar shape, a hint of flowing robes that move against the current of the datastream that enfolds them, and tries to follow. But the crowding ions—balled advertising, jostling users, once a virtual pickpocket, groping for useful programs in other people's toolkits—block her way, and she loses the robed icon at the main exchange node, where the data flows down from the outer nets like a waterfall of lights.

She turns back toward the center of the maze that i the BBS, following the shape of the underlying structural spiral rather than the illusion of shops and storefronts and tented stalls—unfamiliar shop-icons, old names and symbols blanked or greyed or simply missing—heading for a node where someone will surely know where Trouble has gone. Trouble will have left a message there, if she left anything at all. This is free space, unprotected, and the air stinks of it, the salt sea-smell the brainworm gives to undefended bits of data. At any other time, she would stop to taste, to savor, to see what news is drifting in the wind—and maybe especially tonight she should stop, listen to the whispers and shouts and read the posts that fill the message walls, but Trouble is gone, and that matters more than any law. She can hear voices, snatches of conversations, names repeated, no her own, but familiar nonetheless: the netgods have spoke, the oldsters who built and managed the first nets, and they've thrown their weight behind Evans-Tindale. Cerise sneers at that, and doesn't care that the brainworm broadcasts that emotion. The old netwalkers are out of touch with the new conditions, with the better, faster, and wider-band dollie-slots and especially with the brainworm; of course they'd support this law as a way to keep their own power supreme.

In a blank mirror that was once the center of a pair of swinging doors, she sees herself reflected, her icon blonde-girl-in-blue-dress-and-pinnie, the child she never should have been, and then the mirror empties and she puts her hand through it just like Alice and walks, her feet barely touching the illusion of a floor, into a temporary space.

Inside the mirror is a cave of ice, not the warm wood saloon she had expected, lined in IC(E) to keep out the intruders; the cowboys and the piano player are all missing, vanished into chill white silence, and a personal icon stands in the center where the bar had been, a woman-shape dressed like a dance-hall girl in snow-white velvet and silver fringe and silver-spangled stockings, the cloth drawn back into a bustle, cut down at the bodice to reveal breasts like hills of snow. Cerise feels the chill of the IC(E) on her skin, tingling down her spine like danger; she smells a tracker program, sharp as burned cloves, can almost taste the candy-sweet data that lies like shards of glass below the illusory floor. Miss Kitty deals in that data, stolen, borrowed, invented, even imagined, and in the commerce of messages passed unread.

*I'm looking for Trouble,* Certise says, and waits.