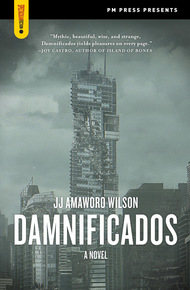

JJ Amaworo Wilson is a German-born, British-educated debut novelist. Based in the U.S., he has lived in 9 countries and visited 60. He is a prizewinning author of over 20 books about language and language learning. Damnificados is his first major fiction work. His short fiction has been published by Penguin, Johns Hopkins University Press, and myriad literary magazines in England and the U.S.

Damnificados is loosely based on the real-life occupation of a half-completed skyscraper in Caracas, Venezuela, the Tower of David. In this fictional version, six hundred "damnificados"—vagabonds and misfits—take over an abandoned urban tower and set up a community complete with schools, stores, beauty salons, bakeries, and a rag-tag defensive militia. Their always heroic (and often hilarious) struggle for survival and dignity pits them against corrupt police, the brutal military, and the tyrannical "owners."

Taking place in an unnamed country at an unspecified time, the novel has elements of magical realism: avenging wolves, biblical floods, massacres involving multilingual ghosts, arrow showers falling to the tune of Beethoven's Ninth, and a trash truck acting as a Trojan horse. The ghosts and miracles woven into the narrative are part of a richly imagined world in which the laws of nature are constantly stretched and the past is always present.

"Should be read by every politician and rich bastard and then force-fed to them—literally, page by page."

– Jimmy Santiago Baca, author of A Place to Stand"Two-headed beasts, biblical floods, dragonflies to the rescue—magical realism threads through this authentic and compelling struggle of men and women—the damnificados—to make a home for themselves against all odds. Into this modern, urban, politically familiar landscape of the 'have-nots' versus the 'haves,' Amaworo Wilson introduces archetypes of hope and redemption that are also deeply familiar—true love, vision quests, the hero's journey, even the remote possibility of a happy ending. These characters, this place, this dream will stay with you long after you've put this book down."

– Sharman Apt Russell, author of Hunger"Only a rare and special talent can take contemporary realities—sad, joyful, infuriating, inspiring—and spin them into legend. In a narrative rich in danger, adventure, humor, romance, and risk, JJ Amaworo Wilson raises essential questions without succumbing to earnestness or didacticism."

– Diane Lefer, author of Confessions of a CarnivoreTHE SKYSCRAPER WAS THE THIRD-TALLEST BUILDING IN THE CITY AND FROM THE HIGHEST floor you could look down on the backs of birds gliding on air. One muggy August afternoon Rolo Torres tried to parachute from the fiftieth floor. The chute stayed shut and he landed face first in a refuse pile.

"At least we don't have to dig a hole to bury the dumb shit," said the mayor.

The building had stood empty for a decade, pockmarked by bullet holes, paint peeling in the sun, flaking away like a layer of skin, and a posse of graffiti artists had looped their messages in cartoon writing on the back of the building: libertad, torre de mierda, cojones, viva la revolución, and a fresco of soldiers in silhouette marching to Hell.

Surrounded as it was by low-rises, the monolith took on the aura of a bully. With its six hundred eyes it watched the world, and its shadow moved like the hands of a clock, blotting out the surrounding bodegas and wastelands and cinder block houses for minutes at a time. Over that decade the glass had fallen out the windows or been smashed by stray birds and bats till the building's eyes were hollows. And with the glass gone, the wind lassoed its ghost-whistles around and through the skyscraper's neck, shooting in and out of its arteries and whooshing down its lungs.

Some winter days the building would sway like a dancer. And when it did, the mayor, perched on a balcony sixty floors up, would cry, "It's gonna fall!" and his wife would tell him to shut the hell up because he was the mayor and he was supposed to be a leader but he was yellow as a streak of lemon and he knew it and his wife knew it and his kids knew it and when he died it was with the whimper of a wounded dog and he soiled his pants in front of his enemies, which by the end was everyone including his wife.

And it is these same damnificados, twenty years on, who crawl out of the darkness one balmy midnight, a raggedy army of beards and grime, heading for the tower. They come from Agua Suja and Minhas and Fellahin and Bordello. They come from Sanguinosa and Blutig and Oameni Morti, cardboard cities and shantytowns on the hills, where the rain makes rivers of mud, where houses slide away. And they drag fraying baskets and polythene bags, soot-stained blankets, coats of crinoline and fake fur. A woman in her fifties pushes a wheelbarrow which carries a three-legged dog. And from out of a nook comes a cripple named Nacho, heaving his wasted body on bandaged crutches, his quick eyes scanning the streets for trouble. Krunk! Trouble! A four-hundred-pound Chinaman emerges foot first from a hole in a wall, kicking down the bricks. Another damnificado. He looks both ways and slings a scarred wooden club over his shoulder.

Some of the damnificados have wrapped their faces in cloths, like lepers, only eyes visible, and their steps are padded as a panther's because many have no shoes to walk in, just rags binding their feet. And others move barefoot, hunched and furtive, two by two, shifting in the shadows for safety.

Slowly and silently they converge on the tower block. And a cat spies them from its roof of corrugated iron and narrows its eyes and purrs its approval. There's nothing like a midnight rumpus to stir a cat. The distant music of sirens droops further and further into oblivion, and then there is no sound save the scampering of mice on stone.

The silence is broken by the roar of a bus as it swings its rump around a corner. A great gouge of smoke bursts out of its exhaust and then the bus convulses to a stop and two filthy, lanky teenagers exit, blond, wiry, carbon copies each of the other, each jumping the final step. Twin damnificados, men of the scarecrow army.

"Wo ist der Grosse? Where is that big bastard?" says the one.

"The tower or the Chinaman?" asks the other.

"Der Turm. Who's the Chinaman?"

"You'll know him when you see him. He's massive. He once killed an ox."

"Who hasn't killed an ox?"

"He strangled it with his bare hands."

Nacho the cripple turns a corner, sees the monolith and stops, thinking this is just as it was foretold all those years ago in Zerbera. He feels the damnificados around him, hears their breathing, recognizes the smells—a musky anthology of old food, sweat, piss, trash. Re-cognizes. Knows again, because he has dreamed of this time and this place. He crabs across the street, out of the shadow. Jaywalks with the wooden muletas under his arms, his lame leg dragging. Knows he is the first and has to be the first. Passes a gateway where Torre de Torres was inscribed on a plaque until the graffiti artists chiseled it down to rey de reyes. King of kings.

And once Nacho is past the sign, the others follow, first the Chinaman, then the twins.

"That's him. He's a bear."

"He's an elephant."

"He's a Chinaman."

"He's a bear."

Then the woman with the dog in the wheelbarrow. The wheel squeaks. She curses the world for her bad luck. Broken wheelbarrow, broken dog. It lies asleep, lulled by the journey from Sanguinosa, its long pale head tipped over the side.

The damnificados cross over. They stand ready. They gaze up at the towering monolith. Babel in black. Streaked concrete. Home from home. They surround it, milling. They wait. They glance at one another. Somewhere a clock chimes twelve.

"Now what?"

"We wait for Nacho. He'll give the word."

Nacho approaches. The doorway is boarded up, a criss-cross of wood hammered in with nails. He motions to the Chinaman, says something low. The Chinaman walks to the door and clasps his club in two hands. He swings once and a board explodes with a crack like a gunshot. Nails jump. With a final kick, it caves in. A small cheer goes up.

A woman's voice: "Now it's ours."

Nacho is overtaken by his army of damnificados. They approach the door and then they hear it. They stop. At first it's a whine but then it drops an octave and then another until it's a low growl. No one moves. The growl comes again. In the doorway, in the darkness, a shape shifts.

"It's a dog."

"It's wild."

They make out movements in the gloom. The creature begins to pace the dusty atrium behind the door. Growls low again. Moves forward. Then a shaft of moonlight breaks open the darkness, zeroing in on the splintered boards as the animal comes closer, bares its fangs. The damnificados stare. Something wrong. A breach of nature. The beast has two heads.