T. Kingfisher is the vaguely absurd pen-name for children's book author Ursula Vernon. This is the name she uses to write books for grown-ups. Under various names, she has won the Hugo, Nebula, WSFS, Mythopoeic and Sequoyah awards. She lives in North Carolina with her husband, dogs, cats and chickens, and when not writing, she likes to wander around the garden and try to photograph weird bugs.

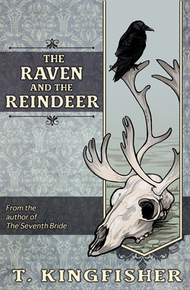

When Gerta's friend Kay is stolen away by the mysterious Snow Queen, it's up to Gerta to find him. Her journey will take her through a dangerous land of snow and witchcraft, accompanied only by a bandit and a talking raven. Can she win her friend's release, or will following her heart take her to unexpected places?

A strange, sly retelling of Hans Christian Andersen's "Snow Queen," by T. Kingfisher, author of "Bryony and Roses" and "The Seventh Bride."

Ursula Vernon's writing under her adult penname T. Kingfisher continues to prove why she is among my favorite authors with the Raven and the Reindeer. This retelling of the classic Snow Queen fairy tale is equal parts humor and pathos with character that are sheer delight. – Terry Mixon, SFWA

"Funny, touching, dark and uplifting by turns, it may be one of the best fairy tale retellings I've ever read… It's an amazing kind novel. Quietly and unapologetically generous of spirit: it made me cry, reading it, because it was just so right, and generous, and gloriously, practically, kind."

– Tor.com “Sleeps With Monsters”"…the research into Finnish customs and Scandinavian living is excellent, and blended perfectly into the narrative without becoming pedantic. It's just such an indulgent joy to be part of Kingfisher's worlds. I want nothing more than for her to take on every single one of Hans Christen Anderson's stories (and the Grimms', while we're at it) and remake them in her own style, so that I can go on indulging in them forever."

– GeeklyInc.com"Simply magical. If you haven't read this one yet, it's the ideal book to curl up with a cup of hot cocoa and a blanket and read on a cold winter's night."

– SFBluestockingOnce upon a time, there was a boy born with frost in his eyes and frost in his heart.

There are a hundred stories about why this happens. Some of them are close to true. Most of them are merely there to absolve the rest of us of blame.

It happens. Sometimes it's no one's fault.

This boy was named Kay. His eyes were blue when he was born, pale as a winter sky. The frost glittered in them, in little flecks of silver around the pupil.

"What lovely eyes!" his grandmother said, rocking the baby on his knee. "He'll be a devil, with eyes like that."

"Lots of babies have blue eyes," said her best friend, who was knitting baby clothes. "They mostly grow out of it."

His grandmother clucked her tongue. "You won't say that when your grandbaby's born."

"I will, too."

"You would, wouldn't you?" Kay's grandmother laughed at that, and her friend smiled. "They'll be great friends, our grandbabies."

"If they don't grow out of that, too."

"Oh, you…" Something displeased Kay and he screwed up his face and squalled. "There. Your eyes will stay blue. Don't listen to that old sourpuss."

The old sourpuss in question only laughed.

The granddaughter was born a few days later, and her eyes were brown. They named her Gerta. She was chubby and good-natured and slept easily through the night.

Kay grew up tall and slim and his eyes stayed pale blue with a ring around them, like the eyes of a sled dog. His grandmother had been right about that.

Whether or not she was right in her other prediction was an open question.

Gerta would have said that Kay was her best and truest friend, that they could tell each other anything and they would take on the world together.

Kay would have said Gerta was the neighbor girl. "She's all right. I guess."

In fact, he did say this, on a number of occasions.

There are not many stories about this sort thing. There ought to be more. Perhaps if there were, the Gertas of the world would learn to recognize it.

Perhaps not. It is hard to see a story when you are standing in the middle of it.

But if Kay had a sled-dog's eyes, Gerta had a dog's loyalty. It did not matter that he ignored her sometimes, or said "It's just the neighbor girl" to the other boys in the town. Those boys did not know what Gerta knew.

When it was cold (and it was often cold) when the snow was piled four feet deep under the eaves (and sometimes higher) then Kay would open the window in his family's garret and Gerta would open the window in hers. They were separated by less than three feet, and there was a little bit of a bridge between them, where Gerta's mother had set up a windowbox.

Then one or the other would step across the gap and into the other one's home. On cold days, the stove would be on and there would usually be something delicious on it—lingonberry juice or mulled cider or a plate of gingerbread.

The two of them would play together for hours as children. They were not much alike. Kay liked puzzles with pieces that you could fit together, and Gerta liked making up stories of heroes and gods and monsters. Gerta was only taller than Kay for three glorious months, when she got her growth spurt and he didn't. Then Kay shot up past her and Gerta never got any taller.

"That's just the way it is," her grandmother said. "We're short, sturdy people. Keeps us below the level of the wind."

"I'd rather be tall and beautiful," said Gerta.

"If wishes were fishes, we'd have herring for dinner."

"We're going to have pickled herring anyway," said Gerta.

"Well, then who knows?" Her grandmother winked at her. "Perhaps there's some point to wishing after all."

As they got older, the children would talk—or Gerta would talk and Kay would comment occasionally, slow sentences falling quiet as snowflakes.

"Sometimes I think that snow could be alive," he said once. "Like a hive of bees."

"I always think of feathers," said Gerta. "Like what if a snow goose flew over us and all the down shook out of its feathers?"

"It would have to be a big goose."

"Or a whole flock of them," Gerta agreed. "A whole flock of geese over the town, flapping their wings, and that's why it's windy too!"

Kay smiled faintly.

Another time he said "I like the world better when it's snowed. You can't see all the ugly bits. It's all pure white."

He did not know that Gerta treasured these statements, saving them up and repeating them to herself at night. They were her great comfort. In summer, when he went around with the other boys and pretended to ignore her, she remembered his words.

She thought I bet he doesn't say things like that to the other boys. That's the part of himself he only shows to me. That's the important bit.

Which only goes to show that you can be both right and completely wrong, all at the same time.

The snow fell and melted and fell again. It fell for two days and then stopped. The sun came out and shone fiercely on the snow, enough to make you blind and dazzled.

The townspeople shoveled the walks and the horses were unhooked from wagons and hooked to sleds.

Gerta stood at the window and gazed out through the frost-rimed panes. The glass squares were very small and her breath turned them white as she stood.

"He's gone out with his friends," said Gerta's grandmother. She was older now, but still knitting clothes for her granddaughter.

"We spent two days talking," said Gerta.

"Then you're probably sick of him by now."

Gerta shook her head. They had worked on a puzzle for a number of hours, and when they finished it at last, Kay had kissed her. It was a new experience and it made her feel strange and squashy. She'd expected…

Well, she wasn't sure what she expected.

His lips had been cool and a bit dry. She wasn't sure if she was supposed to push back with her lips or move her head or just stand there and have it happen.

She was in love with Kay, of course, always had been, so his kiss should have made her feel blissful and alive. She should have woken up from her ordinary life the way a fairy tale princess wakes from an enchanted sleep.

She probably shouldn't have been wondering what she was supposed to do with her lips.

I must have done it wrong. Maybe I was supposed to do something else.

If he'd do it again, maybe I could figure out what I was supposed to do.

In order to kiss her again, Kay would have to be somewhere nearby, not out sledding with his friends. Gerta sighed.

"You should go out with other girls," said her grandmother.

"I don't like the other girls," said Gerta, scowling. "Besides, I'm not like them."

(Kay had told her once that she wasn't much like other girls. It was one of the phrases that she held very close, tucked up in the space beneath her breastbone.)

"In this very town," said her grandmother, "there are at least a dozen girls standing at windows right this very minute saying the exact same thing." She shook out her knitting.

Gerta scowled harder.

"I did the same thing when I was your age," said her grandmother. "I daresay I wasn't like other girls harder than anyone else ever was. I was so unlike other girls that I wasn't even like myself, except on Sundays."

Gerta felt the scowl turn up at the edges and pressed her lips resolutely down.

"Go out with some other boys, then," said her grandmother. "At least meet a few." Almost under her breath, she added "Make Kay sweat a little, for a change."

"I don't like any other boys."

"Yes, and he knows it, too." Her grandmother shook her head. "Wouldn't hurt to meet them. Girls not much older than you are getting married, and I'd hate to have you settle for the boy next door."

"It's not settling," said Gerta, quite shocked. "It's Kay."

"Yes, yes." Her grandmother held up her knitting. "Bother! I'm out of this color yarn, and I did think I'd have enough to finish. You won't mind if your sock turns green at the top, will you, Gerta?"

"One half-green sock?"

"I guarantee none of the other girls will have a sock like it. 'That girl,' they will say, 'that girl is not like other girls. Just look at her socks!'"

Gerta tried to hold onto the scowl, but it melted.

"There's my girl," said her grandmother, pleased. "Do you know, I might have enough yarn to finish it up after all?"

"That's all right," said Gerta. "I think I'd like one half-green sock."

Kay did not kiss her again. Gerta went from the extremes of joy to the depths of despair, often several times in the same day.

He kissed me. That means he loves me.

He hasn't kissed me again. That means I did it wrong.

When his dad made a stupid joke, Kay rolled his eyes and smiled at me. That means…that means…

In the old days, Gerta knew, people used to write questions on reindeer bones and throw them into bonfires. The way the bones cracked told you the answers.

I wish I had a bonfire. And a reindeer skeleton.

Hard luck for the reindeer, though. I'd want it to be a very old reindeer who died peacefully.

It occurred to her that she could simply ask Kay if he loved her.

I'd die. I'd just die. On the spot. Immediately.

"Are you feeling well, child?" asked her grandmother. "You've gone all flushed."

"I'm fine!" said Gerta. She snatched up her mittens and ran outside.

The center of town was full of horse-drawn sledges, but there was a very fine sledding hill just two streets away. The road was never shoveled because it was much too steep for horses, so everyone took their sleds there.

She saw Kay with his sled. He wasn't wearing mittens or a hat, but he didn't look cold. His friends were more heavily wrapped.

Gerta felt self-conscious. It was all very well to be short and sturdy, but when she was bundled up in coats, she felt wider than she was tall.

"Hey, Gerta," said one of the boys, pulling his scarf down so he could talk. He was a shorter boy with dark, curly hair.

Kay looked her over coolly and dipped his head once.

"You want to have a go at the hill?" asked the curly-haired boy. "You can use my sled."

"Well…" said Gerta. She was hoping Kay would offer her his sled.

Kay picked up his sled instead. "I'm done," he announced to no one in particular. "I'm going home."

"I'll come with you," said Gerta. "Thanks, though."

The curly-haired boy shrugged. "Come back if you change your mind."

They walked home together. Gerta had to stretch her legs to keep up.

"What's your friend's name?" she asked. "He seemed nice."

"Bran." Kay's jaw was set. He looked angry. Gerta wondered if she'd done something wrong.

I shouldn't have said he seemed nice. He probably thinks I like Bran more than him. Oh that was a stupid thing to say.

They walked three blocks, while Gerta tried to think of something to say that would let him know that she liked him best of all.

"I wish it would snow again," said Kay abruptly.

"Oh, me too!" said Gerta, who would have agreed to anything at this point.

"A really big storm," said Kay. "A blizzard."

Gerta was less sure about this. "Why a blizzard?"

"So everything is covered," said Kay. "Everything's white. And crisp. And when you walk on the snow, it's like you're the only person in the world."

"It sounds beautiful."

"You could walk for miles," said Kay, "and listen to the wind."

"Wouldn't it be cold?"

"Yes. That's the point."

"Oh."

They kept walking. Gerta felt as if she were trudging. The snow was loose and wet and every footstep sank deep.

She glanced at Kay. "Aren't you cold right now, though? You don't have a hat."

"I never get cold," said Kay.

Kay got his wish. The snow came down that night like the end of the world. Wind howled under the eaves and frost chewed on the edges of the windows. And the snow fell and fell and fell.

"A hundred year storm," said Gerta's grandmother. "The Snow Queen rides tonight."

Gerta and Kay had been standing at the window, watching the snow fall. Gerta's nose was nearly frozen off, but Kay was there and she was very happy.

"Who's the Snow Queen?" asked Kay.

"The queen of all this," said Gerta's grandmother. "The mistress of ice. She has a palace as far north as north. She rides in a sleigh made of ice and pulled by great white bears who used to be men." (Gerta's grandmother knew how a story ought to be told, even if she wasn't always sure how much yarn went into a sock.)

Kay raised an eyebrow and sipped his hot cider.

"How did they turn into bears?" asked Gerta.

"The Snow Queen enchanted them," said her grandmother. "She's Circe's cold cousin, always turning men into other beasts. Not pigs, though. She likes bears and seals and wolves and all the creatures of ice."

"Sounds rotten of her," said Gerta.

"Oh, I daresay she had her reasons," said her grandmother, who could think of a few men that would have been much improved by spending time as an enchanted seal.

"What does she look like?" asked Kay dreamily.

"White as white," said Gerta's grandmother. "She wears the furs of white foxes and her sleigh is cut from birch trees." She took a sip of her cider. "The snow follows her wherever she goes. When she's in a temper, she brings down ice storms and the trees fall down like matchsticks."

"Why would she do that?" asked Gerta.

Her grandmother shrugged. "She's the Snow Queen. It's what she does."

She got up to mull more cider. Kay and Gerta stood at the window, watching the snow whirl down.

They were shoulder to shoulder in the window. Gerta leaned on Kay a little, and he leaned back.

She felt a rush of relief. He isn't still be angry with me about this morning. If he was angry with me at all…

She wondered if he would kiss her again. Maybe this time she could figure out what she was supposed to do with her lips.

But he didn't, and the minutes stretched out and her grandmother came back into the room with more cider, bustling back and forth between the counter and the stove.

Gerta stifled a sigh. She had lived next door to Kay her entire life, and sometimes he was cold and sometimes he was warm. There never seemed to be any pattern to it. He might spend an entire day playing adventures with her, or letting her help with a puzzle, and then the next day he'd shrug one shoulder when she came near and refused to meet her eyes.

Oh well. He kissed me once. He knows I'm here, and nearly grown up. And he doesn't have an understanding with any other girl, because he would have told me.

Her lips twisted, looking out at the snow. She could be sure of this. It would not have occurred to Kay that telling her about another girl would make her jealous.

That's 'cos we're best friends. And best friends tell each other everything.

She slid a glance at Kay. His dark eyelashes framed his pale blue eyes, as he drank in the blowing snow. Whatever he was thinking, he kept it to himself.

That night Gerta slept in her trundlebed near the stove. She curled up under the red patched quilt and there she dreamed.

She dreamed that the snow had stopped and the moonlight glowed through the window. Some sound had roused her attention—a high thin chiming, like bridle bells.

I could get up.

It's so warm here. It'll be cold by the window.

She looked up into the shadows of the ceiling. The rafters were hung with baskets. Her grandmother baked flat, hard loaves of bread and strung them on wooden poles to keep them. They were delicious crumbled up and soaked in the juices of rabbit or chicken or deer.

The sound came again. Tingatingatinga-ting-ting-ting.

She pushed off her quilt and walked to the window.

Everything was white and blue and silver. The walls of the building across the alley were dark smears, crowned with thick white cliffs of snow.

Tingatingatingatinga…

Down the rooftop came a white sleigh, cut from shining birch wood. Bells rang merrily along the traces.

There is a sleigh on the roof, Gerda thought, and then Ah. I am dreaming.

Because she was dreaming, she did not question that the sleigh was pulled by snow-white otters. They slipped and slithered down the slant of the roof, sliding over each other, a river of white fur and black eyes and arched white whiskers. Gerda kept expecting the traces to get tangled, but somehow the sled kept moving forward.

At the edge of the roof, the sleigh halted. The otters pulled up, chuckling and chirping to each other in liquid voices. They were larger than any otters that Gerda had ever seen. They had pale blue bridles with silver bells and their webbed feet moved across the snow like snowshoes.

Gerta was so fascinated by the otters that she hadn't looked at the sled at all. She tore her eyes away.

It was a relatively small sleigh, only large enough for one or two people. Of course, thought Gerta, otters probably can't pull very much weight, not like horses or reindeer…

The runners were ivory, carved in the shape of seals that leapt and slid over one another, very much like the otters. The trim was ice blue and matched the bridles.

Seated in the sleigh was a woman.

Gerta, who had been highly delighted by the sleigh and the otters, felt the first chill.

The woman was very tall and very slim. Her face was as angular as a fox and her hair was white, yet somehow she did not look old. She sat in the sled with her hands on the reins and looked around, and the world seemed to change as she looked at it.

The buildings and the streets became small and shabby. The town looked old and grimy. Gerta, who loved her town, caught her breath at the injustice of it, because nothing about the town had changed, it was only that the woman in the sleigh was so far above it all.

Only the snow remained clean and white, still glowing in the moonlight. The woman in the sleigh did not look at the moon, and some small, wise part of Gerta thought I bet she can't. It doesn't change if you look at it. No matter how pale and pure and perfect you are, the moon is even more perfect than you are.

Gerta, who was short and sturdy and turned pink when she hurried, felt her hands clench into fists.

I wish I would wake up. The otters were wonderful but I don't want to see the rest of this.

The Snow Queen—surely it must be the Snow Queen, surely it could be no one else—stepped out of the sleigh. She wore white deerskin boots, exquisitely small, and left no track on the snow.

Gerta jerked back, suddenly afraid that the Snow Queen would see her.

She can't touch me. If she touches me, something bad will happen.

For a moment, she thought that she was safe. The woman would leave. The dream would end and in the morning, perhaps all she would remember would be the otters.

Then a pale oval appeared at the other window, directly across from Gerta.

It was Kay.

No! Gerta wanted to yell. No, go back inside, don't let her see you!

But this was a dream and dreams are the sisters of nightmares. She could not yell and her hands curled into useless fists on the window frame.

The Snow Queen walked to the edge of the roof and smiled down at Kay.

Kay's mouth fell open.

For a long moment, they looked at each other. Their eyes, Gerta saw, were the same color.

The Snow Queen crooked her finger, curled it back.

No! Kay, no, run away! If she touches you something bad will happen!

Kay pushed the window open and began to climb out.

The iron railings between the two windows, the highway on which Kay and Gerta moved back and forth, was slick with ice. Gerta covered her mouth with her hands, afraid that he might fall—

—it's better if he falls, the snow is thick, he'll probably live, if she touches him he'll die or worse—

The Snow Queen reached down and took his hand.

Kay gasped. Even through the glass, Gerta could hear it. He gasped and for a single heartbeat, his eyes glowed like ice in the moonlight.

Her bones were fine and delicate, but her strength was enormous. The Snow Queen pulled him onto the rooftop and helped him into her sled.

Gerta couldn't help it. She slapped a hand against the cold glass. "Kay!" she cried. Her voice seemed to come from very far away.

He did not look around. He settled himself in the sled, under a blanket trimmed with white fox-fur.

The Snow Queen turned and looked down at Gerta.

Gerta jerked back as if she'd been lashed with a whip.

The Snow Queen's gaze was no kinder to her than it was to the town around them. Gerta felt young and weak and disgustingly mortal. She was a stinking, bleating creature, a heifer-calf with dirt tangled in her tail. She did not deserve to share the same air with the magnificent Snow Queen.

Her back wanted to bow and her legs wanted to buckle. She wanted to grovel and apologize for existing. She wanted to hide her eyes and crawl away.

I can't—I can't—she's got Kay—I've got to stop her, but she's so much better than me—

And then, as if from a very great distance, she thought, Grandmother wouldn't crawl.

Gerta sank down to her knees under the window—but she did not look away from the Snow Queen's eyes.

The Queen reared back a little, like a great swan arching her neck. She turned back toward Kay.

Gerta gasped as if a stranglehold had suddenly been broken.

The Queen stepped into the sleigh, bent down, and kissed Kay on the cheek.

She slapped the reins and the otters rose up, cheerful and chiming. The sleigh began to move down the edge of the rooftop.

"No," whispered Gerta. Her throat was hoarse, as if she had been screaming. A whisper was all she could manage. "No!"

The Snow Queen looked back to her.

She smiled.

It was a nasty, cold smile, but at the same time, it was more human than any expression Gerta had seen on the Snow Queen's face. It was a smile that said I have something you want, and it's mine now, and you'll never get it back.

Kay gazed forward and never looked back.

The otters leapt from the roof and the sleigh followed. It would have been an enormous drop, but it did not occur to Gerta to worry. They would ride a snow flurry down or a sheet of icicles. The Snow Queen would not be stopped by anything so foolish as a three-story building.

They were gone.

The only tracks on the rooftop were the holes left by Kay's feet, and they filled up with snow so fast that they might as well not have been there at all.

Gerta stayed at the window until her teeth chattered, but there was no point. She knew there was no point.

She crept to the trundle bed and pulled the quilt over her head.

It was a dream, thought Gerta forlornly. It was all a dream. I'll wake up and I won't remember it very well at all and we'll laugh about it. I hope I remember the otters, but I hope I forget her.

In the morning, Kay was gone.

There is a great deal that goes on when someone goes missing, and none of it is good. It is a tiresome sort of panic, because there is no end to it. It goes on and on and on until you are hollowed out and empty and still there is no end.

First the families told each other that Kay was fine, that he had just stepped out to go sledding. It was a bit odd that he had left a puzzle half-done like that, but boys were odd sometimes.

Then they told each other that he had gotten lost but would turn up shortly. They would laugh about how foolish they were being.

Then they told each other that he was clearly lost in the snow but he was a smart lad and would dig down where he was and be safe.

Eventually the snow melted and the sun shone down and thaw came and went and they stopped telling each other anything at all.

Through all those long weeks, Gerta felt as if she was standing a little apart from everyone else. It was as if her dream had raised a wall of ice and the world was on the far side of it.

If it was a dream.

It can't have been a dream.

It must have been a dream.

I know what I saw.

He wouldn't have gone out in a blizzard. He wasn't a fool.

She lived the last moments of the dream a thousand times, seeing Kay look up, his lips parted, looking at the strange cold woman with an expression of lust and worship. The expression made her stomach clench like a fist.

I want it to be a dream because I don't want him to look at anyone else like that.

I want it to be true because I don't want him to be dead!

When she put it like that, there was no choice at all.

The woman had been so beautiful. Gerta's heart ached for how beautiful she had been. She wanted to be able to turn to someone and say "Did you see that?"

But no one else had seen her. Perhaps there had been no one to see.

And the wall of ice stood between Gerta and the rest of the world, and she could not reach through it to say "He isn't dead. I saw him leaving in a dream."

Gerta's grandmother made hot tea in endless amounts, melting snow into water and throwing handfuls of herbs into it. The tea was only thing that Kay's grandmother would drink.

"My sweet little boy," whispered Kay's grandmother, her voice gone hoarse with weeping. "My sweet boy. Where did he go?"

"You'll do no good following him into the next world," said Gerta's grandmother bluntly. "Eat some soup."

Gerta silently appeared with soup in a mug and the old woman drank it. She had become old, it seemed, in the time since the spring thaw.

When she slept at last, her hair was a silver fan over the pillow. Gerta's grandmother stroked it, her face lined and weary. In the distance, they could hear water dripping from the eaves, drip drip drip as the ice melted away.

Perhaps it was the thaw that made the first crack in the wall of ice around Gerta. Perhaps it was the steam from the soup or the tears on the old woman's pillow.

"Grandmother?"

"Eh? Yes, child?"

"Is the Snow Queen real?" asked Gerta.

Her grandmother looked at her for a moment as if she could not understand the question. After a moment, she said "I suppose she's real enough. Stranger things have walked the earth and left stories behind them."

"I saw her," said Gerta. "The night Kay—that night. I saw a sleigh on the roof. There was a woman in it, all over white. I thought I was dreaming, but Kay's gone. He's not coming back. I think she has him."

Her grandmother made the sign to avert evil.

"Tell me about this woman."

Gerta tried, at great length. Her tongue stumbled on some of the descriptions—on how beautiful the woman was, and on the look on Kay's face. But parts of it she remembered clearly, like how the sleigh had looked and the way the runners had been a hundred carved ivory seals, slithering and sliding over top of one another.

Her grandmother drew in a sharp breath at that, for she had heard such things before, and she was certain that she had never mentioned them aloud.

After a long time, she said "You've never lied, Gerta, even when you were little and trying to get out of trouble. Even when you were trying to cover up for Kay, you'd just stand there, stubborn as a little stone, and not say anything. If you say you saw the Snow Queen, I'll not disbelieve you now."

"As far north as north," said Gerta. She took a deep breath and let it out. She was aware that what she was doing was quite unspeakably mad. "I have to go after him."

Her grandmother closed her eyes. After a moment, she said, "I should tell you not to go. I should tell you one child lost is enough."

"But you won't," said Gerta.

"But I won't." She looked back at her oldest and dearest friend, asleep on the couch with the lines of age and grief like fissures in her skin. "I'm an old fool. I told you and Kay about the Snow Queen. I should have known he'd take it to heart. There always was a spot of ice in him."

"You couldn't know—" said Gerta.

"I should have known. Things come when they're called." She scrubbed her hands over her own face. "If I lose you, it's no more than I deserve."

"I'll be careful," said Gerta. "You won't lose me. I'll just go north a little way and ask if anyone's seen him."

"Yes." Her grandmother began hurrying around the room. "Take some food. I don't want you starving."

Gerta slung her pack over her back. "I will. Is there anything else I can do, Grandmother? Against the Snow Queen?"

The old woman shook her head. "In all the old stories, the only thing that ever won was love. And occasionally a good sharp knife."

"I'll take the kitchen knife with me, then," said Gerta.

"Mind that you do. And wear your boots." She kissed her granddaughter on the forehead. "An old woman's grace go with you, child."

Gerta went.