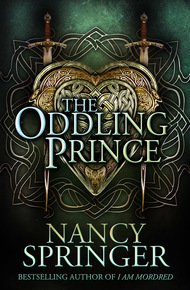

Nancy Springer is the award-winning author of more than fifty novels, including the Books of Isle fantasy series, the Enola Holmes mystery series and a plethora of magical realism, women's fiction, contemporary young adult and other titles. She received the James Tiptree Jr. Award for Larque on the Wing, the Edgar Allan Poe Award for her juvenile mysteries Toughing It and Looking for Jamie Bridger, and has been a frequent nominee for the Nebula and World Fantasy awards. Forthcoming from Tachyon Publishing, The Oddling Prince is a heartfelt return to her beginnings, forty years ago, in the fantasy genre. She currently lives in the Florida Panhandle, where she rescues feral cats and enjoys the vibrant wildlife of the wetlands.

In the ancient moors of Scotland, the king of Calidon lies on his deathbed, cursed by a ring that cannot be removed from his finger. When a mysterious fey stranger appears to save the king, he also carries a secret that could tear the royal family apart.

The kingdom's only hope will lie with two young men raised worlds apart. Aric is the beloved heir to the throne of Calidon; Albaric is clearly of noble origin yet strangely out of place.

The Oddling Prince is a tale of brothers whose love and loyalty to each other is such that it defies impending warfare, sundering seas, fated hatred, and the very course of time itself. In her long-awaited new fantasy novel, Nancy Springer (the Books of Isle series) explores the darkness of the human heart as well as its unceasing capacity for love.

I have loved Nancy's work since I read The White Hart back in 1979. It was in summer camp in Long Island, and I borrowed the book from my friend Kirsten Bakis—who also went on to become an award-winning writer. Nancy Springer has of course won all the awards—far too many to mention here. To include her newest book in this story bundle gives me this—dare I say—fey sense of coming full circle with childhood me. – Sandra Kasturi

"Lyrical and lovely, The Oddling Prince feels both fresh and like a classic ballad that's been part of the English canon for centuries."

– Sarah Beth Durst, award-winning author of the Queens of Renthia series"The Oddling Prince is Nancy Springer at her very best. If you don't know her work—which seems most unlikely—The Oddling Prince is the perfect place to start!"

– Peter S. Beagle, author of Summerlong"[10/10 stars] This is luminous writing that enfolds the reader like a spell from the very first page . . . Hold onto your bows and arrows Elflings, we might have an early contender for the best fantasy novel of 2018"

– Starburst"An out-of-the-ordinary fairy tale that can stand shoulder-to-shoulder with work by Tanith Lee and C.J. Cherryh."

– Asimov’s SF"Fast-moving, full of surprises, and yet infinitely satisfying. Every time you think you know what's going to happen Springer pulls a new but perfect rabbit out of the hat."

– Brenda W. Clough, author of How Like A God and A Most Dangerous WomanCHAPTER THE FIRST

Spirits coaxed and called, sang and sighed in the wind outside the benighted tower where I sat beside my dying father, the king. The king! Six feet tall, golden bearded, and strong as a bear, but struck down in his prime by—by a visible mystery. On the third finger of his left hand glowed the uncanny thing, the ring, its own fey light enough to show me my mother's still, white-clad form on the other side of the bed.

How the ring had come onto my father's hand, no one could fathom. Only a month ago, on a fair spring day when the furze bloomed yellow and the thistles raised their crimson heads, we had gone a-hawking, he and I and our retainers, to the hills high above the sea. The hawks had flown well, so that we each carried a brace of grouse or hare slung from our saddles. But that afternoon as we rode homeward down ferny glens, the king, my father, had noticed the ring shining, no color, all colors, on his hand. We had all halted to gaze upon it and exclaim over it and wonder at it, for when he tried to slip it off to show it to us, it would not heed his touch or obey his will. It stayed where it was like a scar. And how it had come to be there, on the finger nearest his heart, he knew not, nor did any of us.

How or why it had sickened him, no one knew either. But since that day, he had not been able to eat, or sleep, and fever burned him away from within, until now, four short weeks later, he lay gaunt and senseless. Many men, strong and wise, had tried to remove the ring, with unguents, with spells, by main force, but it would not stir from his finger. To cut the finger off, to mutilate the personage of the king, would have doomed some portion of Calidon, his kingdom, to be hacked away, destroyed by the barbaric Tartan tribes ever threatening from the Craglands. This could not be. Yet for some reason no one knew, the ring had doomed the king.

My father. How could he lie dying?

Wait!

I sprang to my feet, snatching up a candle for better light, and yes! For the first time in many a day, my father had opened his eyes. And he looked straight at me. But those were not the brave bright eyes I knew; their blue was like shadows on snow.

"Bard?" Mother called to him by her pet name for him.

His dim gaze shifted to her. "My true love," he said in a voice that seemed to echo from a great distance, "it is time. Only let me touch once more your face."

She pushed her white head drapery back over her shoulder, knelt beside him, and lifted his hand—for he had no strength to do it himself—she lifted his right hand to her face, and kissed it, and laid it against the flowing seal-brown hair at her temple.

Then I understood that this was the lucid interval sometimes granted to great men before their—death. . . .

Such a rebel storm surged within me that it thundered in my ears. I snatched up my father's hand lying inert outside the bedclothes that swaddled him to his neck. With both hands, I seized the ring and pulled. I could feel the ring's glowering heat and its sullen, mocking defiance as I tugged, tugged, without moving it an iota. Cursing it, I strained against it to the utmost, and it flickered like small lightning, stinging my fingers as if in warning of what it could do to me if I persisted. I gasped, yet gripped all the harder—

"Aric, no!" my father's faraway voice commanded. "Will it help us if the freakish thing takes you too?"

I ceased the struggle yet still held his hand. "But this cannot be," I cried. "You cannot leave! Your throne, your people, we need you!"

Many folk adored him, but none so much as I. Perhaps a few minds within the castle were sufficiently scheming to think that I, his only son—indeed, his only living child—had somehow done this thing, so that I, a mere youth seventeen years of age, could take his throne in his stead. But if they thought such evil, they were sorely wrong. I knew myself unready to succeed him. A prince I was, yes, but in looks no more than passable—no comelier or taller than most men—and in prowess, no better with sword or lance or horses or—or anything. I had quested nowhere, had wooed no true love, I was—I felt myself nothing compared to my father. I loved him. I would have given anything, anything, my own fingers cut off, to make him well and strong again.

"Aric," he bespoke me gently, "you are my beloved son and my living pride. It is hard, but you will do—"

Do what, I never knew, for even louder than the keening of the wind around the tower rose cries from the courtyard below, the shouts of guards and, worse, the screams of men in terror, warriors who would face battle-axes without a whimper now shrieking fit to tear their throats out.

"It's Death come in," moaned one of my mother's handwomen from the shadows at the back of the room.

"Hush," my mother told her.

"Invaders," Father muttered. "Bastard Domberk can't wait till I die. Aric—"

I gripped his hand hard, dropped it, and ran out of the room, for lacking the king's leadership, all the castle was my responsibility. At breakneck speed I leapt down the tower steps, through the great hall and out toward the courtyard's torch-lit darkness.

But I halted on the wide stone steps of the keep, struck dumb by the sight before me.

A rider. On horseback.

Only one single rider and horse.

But they were such a rider and such a horse as no mortal had ever seen.

In the middle of the courtyard, the rider and his horse stood like a great alabaster statue surrounded by a multitude of pale ovals, the frightened faces of guards and soldiers with their swords out, or their pikes raised, or their bows with arrows nocked to the drawn strings. Yet he, the horseback rider, sat at ease among them as if on a coracle floating amid water lilies.

A slim youth. Perhaps no older than I.

He drew no weapon.

His hands stirred not from the reins.

He gazed straight ahead of him as if in a dream.

He and his milk-white steed, both horse and rider far too beautiful to belong to this mortal world, shone in the night. They glimmered head to foot as if they carried moonlight within them.

My neck hairs prickled at the sight. My heart halted like my feet, like my staring face, and for a moment I felt as if it might stop entirely. But I could not weaken; a king's son is not permitted to weaken, ever. With all the force of my father's authority, I shouted at the guards and soldiers. "Hold! Fall back!" I commanded. "Would you attack one who offers you no harm?" For the honor of my father's hospitality was at stake, be the visitor mortal or—or otherwise.

Only too willing to fall back, still the men-at-arms did not lower their weapons. And they continued to cry out, "It's fey!" "Uncanny!" ". . . across the moat treading on top of the water, through the iron of the portcullis and the wood of the gate . . ." "It's not of this world. Belike it's Death!"