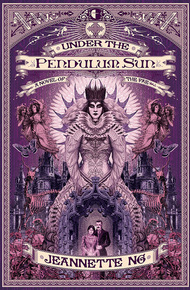

Jeannette Ng is originally from Hong Kong but now lives in Durham, UK. Her MA in Medieval and Renaissance Studies fed into an interest in medieval and missionary theology, which in turn spawned her love for writing gothic fantasy with a theological twist. She runs live roleplay games and is active within the costuming community, running a popular blog.

Victorian missionaries travel into the heart of the newly discovered lands of the Fae, in a stunningly different fantasy that mixes Crimson Peak with Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell.

Catherine Helstone's brother, Laon, has disappeared in Arcadia, legendary land of the magical fae. Desperate for news of him, she makes the perilous journey, but once there, she finds herself alone and isolated in the sinister house of Gethsemane. At last there comes news: her beloved brother is riding to be reunited with her soon – but the Queen of the Fae and her insane court are hard on his heels.

What if the British Empire discovered Fairyland – and promptly sent missionaries there? That's the initial premise of this gorgeous novel, which I adore. Ng's debut is a charged romance and Gothic mystery with a high concept that simply can't be beaten. – Lavie Tidhar

"An evocative, claustrophobic Gothic novel with strikingly creepy set-pieces, which repeatedly dislocates its reader's and characters' worldview in a forceful examination of faith and the power of stories."

– Aliette de Bodard, Nebula, Locus and BSFA Award-winning author of The House of Shattered Wings"Intriguing... fascinating."

– Publishers Weekly"The world-building and atmosphere are just incredible. It's especially gripping because the normal rules don't apply, and nothing is as it seems."

– Syfy Wire, The 10 Best Sci-Fi & Fantasy Books of 2017"An opulently atmospheric piece of neo-Victorian fantasy set in a 19th century in which the British are sending missionaries to Fairyland. It's a strange, brooding and occasionally perverse debut."

– The Guardian, The Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of 2017"A brilliant fantasy that challenges the characters' faith and hearts, and creates a world entirely of its own."

– Scifi NowMy brother and I grew up dreaming of new worlds.

Our father had owned a paltry library of books and a

subscription to the most fashionable periodicals, all of which we gleefully devoured. We would linger by the gate, impatient for the post that would bring new sustenance for our hungry imaginations. Bored of waiting, we told each other stories of what could be. I remember my brother, Laon, finding one of our tin soldiers at the bottom of his pocket. The red paint was barely worn and it looked up at me with a long-suffering expression. I snatched it from Laon's hand, declaring it the Duke of Wellington, and ran off claiming that the two of us

would adventure together. Like Lord Byron or Marco Polo.

We invented whole new worlds for our soldiers to explore: Gaaldine, Exina, Alcona, Zamorna. From our father's books we learnt of pilgrims and missionaries and explorers, and so we wrote of grand journeys, long and winding. As we read of the discovery of the Americas, of the distant Orient, and of strange Arcadia we added similar places to our ever more intricate maps. We mimicked the newspapers and periodicals we read, writing new ones for our tin soldiers. In the tiniest, tiniest writing, we detailed their exploits, the politics of their parliaments, and the scandals of their socialites.

But for all our stories, our imaginations were small and provincial. For the talk of tropics and deserts, our childish fictions filled them with the same oaks and aspens that grew in our garden. We built on their landscape, exotic buildings that were just our little whitewashed church in Birdforth in disguise. We rained down on strange soil the same Yorkshire rain as that which drenched our skins and drove us inside, peeling off our clothes, housebound by the weather and desperate for diversion.

As such, I could never have imagined Arcadia.

I was familiar with all the tales, mind. The first explorers had spun overwrought stories upon their return: Until I laid eyes upon the Faelands, I was blind, and now I see. I have never seen colour, nor grandeur, nor wonder, until I saw the shores of Arcadia. Later travellers were more prosaic, but still offered no adequate description. There were few maps and fewer landscapes available, and almost all of them had been denounced by one explorer or another as fraudulent.

For all the many contradictory theories I had read on the relationship between our world and that of the fae, I was no more enlightened. It was said to be underground, but not. It overlaid our own, but not. It was another place, but not.

All I do know was this: Our ship, The Quiet, sailed in circles on the North Sea for six whole weeks. On the dawn of the first day of the seventh week, my wavering compass informed me that we were heading straight back towards smog-shrouded London.

Nervously, I clutched my compass. My brother had given it to me before he left for Arcadia to become a missionary. He was among the first to be tasked to bring the Word of God to the Fair Folk. He had been there three years now and had been nothing but terse in his correspondence. I tried to swallow the worry that consumed me, but it knotted around my heart.

That was when I caught my first glimpse of the Faelands.

Impossibly white cliffs rose from the white sea foam. For a moment my mind feared it to be Dover, that I had simply returned to those mundane cliffs of chalk and stone, that no foreign land awaited me.

Yet those cliffs were too white, too stark. They could not be Dover.

Behind them I expected the rolling hills of home. But instead the landscape was jagged and jutting knife-sharp from the sea. It seemed cobbled together, each part eerily familiar but set against something other. I recognised the leering profile of a hill, the knuckle-like crest of a mountain. Yet as wind and wave shifted the shapes, it all seemed different again and my strained eyes watered.

The Quiet glided gull-like into a wide, wide river. Unfamiliar structures sprawled against the green grey mass of the land in arching, crumbling lines. Squinting, I made out the spined turrets, barbed roofs and oddly leaning walls. For a moment I thought the town to be an endless dragon coiled around the edge of the harbour, huffing smoke from its distended nostrils. It shimmered, the shingled roofs seeming scale-like, and then it shifted.

I blinked, and buildings were back to where I remembered them. There was no dragon made of shifting structures. Just a town of crowded streets.

The ship heaved under our feet like an unruly stallion. A shout broke out among the sailors in words I didn't understand. They started busying. As they clambered up and down the ratlines and hauled rope this way and that, they muttered invocations under their breath. I wanted to chide them for their superstition but we were sailing to Arcadia and none of it made any sense.

I tried to stay out of the way as the sailors blasphemously crossed themselves in the name of salt, sea and soil.

An unnatural wind curled around the sail, whipping it back and forth. It fluttered full and then deflated with each breath of the wind. The Quiet became anything but as the timber groaned. The cabin boy flung his arms around the prow and cooed at it.

It was a long while before the ship was tamed and brought to shore.

And then I was simply there, stepping unsteadily from the ship into the shamble of a docks. Twisting streets full of seeming people reminded me of crowded London.

The ground was a shock to my feet, and I staggered. My carpet bag and trunk joined me on the docks. I fumbled for my documents and scanned the milling crowd for my guide. I tried not to notice the oddities of each figure – the strange colours and the wings and the horns. There would be time aplenty for the wonder of Arcadia once my bags had been unpacked and I had found my brother.

"Miss Catherine Helstone, I presume? The missionary's sister?"

With an upturned nose, round chin and soft, brown eyes, the woman I turned to meet was perhaps one of the least ethereal people I'd ever met. She was shorter than me. But as her skirts hung long and limp, without a murmur of wave or curve, her figure seemed tall and lank. She dressed in sombre, mortal colours, her gown being a muddy shade of navy blue and her shawl more grey than white.

A smile spread across her freckled cheeks as I nodded.

"I thought I recognised you," she said. "You look just like your brother."

"I do?" Though Laon and I shared the same dark hair and strong nose, few remarked on our resemblance. Features that were handsome on a man were becoming on a woman's frame.

"I'm Ariel Davenport, as I'm sure you know. Your guide."

"I am very pleased to finally meet you," I said. We had exchanged a handful of letters through the Missionary Society in preparation of my journey.

She shook my hand vigorously between her two clasped

ones and swooped in two sharp kisses. Her smile getting

wider, she added, "Though I'm not the real one."

"I'm… I'm not sure I follow."

"I'm not the real Ariel Davenport, you see." There was an unpleasant edge to her laugh; it was a touch too brittle. "I'm her changeling."

"Her changeling?" Many of the intermediaries between the fae and humans were said to be changelings. One of Captain Cook's botanists was said to have learnt of their fae origins upon arrival to Arcadia and was conscripted to their cause. Despite such accounts, changelings never seemed quite real to me. But then, given how sheltered I had been, the French were never quite real. "So you were raised as her–"

Ariel Davenport gave an exasperated sigh and rolled her eyes at my ignorance. "She was a human child, I was a fairymade simulacrum of a human child. We traded places. I grew up there and she grew up here."

"What became of her?" I asked.

"That's not for me to tell." She gave me a disarmingly lopsided smile and in an impeccably proper accent, added, "And it's hardly polite to ask."

"I- I'm sorry," I stuttered. I dropped my gaze. Our nanny, Tessie, used to keep a pair of steel scissors by our beds to ward off faerie abductors. In restlessness and boredom, I once said to Laon that we should close the scissors, so that they no longer formed the sign of the cross, and invite in the fae. He was horrified. And so I never suggested it again.

"Regardless, now I'm here again. Because I'm useful to them and I understand you humans," said Miss Davenport. "Speaking of which, I am most remiss in my duties. I should hardly keep you talking here all day." She waved for an expectant-looking porter to hoist up my trunk onto his shoulders. His sallow skin glinted green as it caught the sunlight.