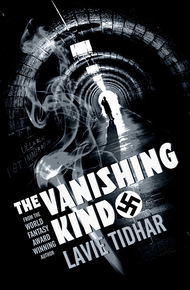

British Science Fiction, British Fantasy, and World Fantasy Award winning author Lavie Tidhar (A Man Lies Dreaming, The Escapement, Unholy Land, Circumference of the World) is an acclaimed author of literature, science fiction, fantasy, graphic novels, and middle grade fiction. Tidhar received the Campbell, Seiun, Geffen, and Neukom Literary awards for the novel Central Station, which has been translated into more than ten languages. He is a book columnist for the Washington Post, and is the editor of the Best of World Science Fiction anthology series. Tidhar has lived in Israel, Vanuatu, Laos, and South Africa. He currently resides with his family in London.

"London after the war wasn't a place you went to on holiday…"

Gunther Sloam comes to Nazi-occupied London in search of an old flame. But when she turns up dead, Gunther is accused of the crime…

Moving through the dark streets of London, pursued by the enigmatic Everly of the British Gestapo, Gunther is in way over his head. London after the Nazi occupation is a place haunted by shadows, and everyone he meets is lying to him. As Gunther gets drawn into a deadly web of conspiracy, illicit drug dealing, prostitution and blackmail, the only question is: can he stay alive long enough to find answers?

One of my own favourite recent works, this is an alternate history noir story set in Nazi-occupied London, where a German screenwriter goes in search of an old flame who has gone missing... – Lavie Tidhar

"Perhaps the best novella of the year"

– Locus"Pretty close to perfect"

– SFcrowsnest1

During the rebuilding of London in the 1950s they had erected a large Ferris wheel on the south bank of the Thames. When it was opened, it cost 2 Reichsmarks for a ride, but it was seldom busy. London after the war wasn't a place you went to on holiday.

Gunther Sloam came to London in the autumn, which is when I first became acquainted with him. He was neither too tall nor too short, but an unassuming man in a good suit and a worn fedora. He could have been a shopkeeper or a traveling salesman, though he was neither. Before the war he had been a screenwriter in Berlin.

He came following a woman, which is how this kind of story usually starts. She had written to him two weeks earlier, c/o the Tobis Film Syndikat in Berlin, and a friend who was still working there eventually passed him her note. It read:

My dear Gunther,

I am in London and I think I am in trouble. I fear my life is in danger. Please, if you continue to remember me fondly, come at once. I am residing at 47 Dean Street, Soho. If I am not there, ask for the dwarf.

Yours, ever,

Ulla.

The note had been smudged with a red lipstick kiss.

It was a week from the time the letter was sent, to Gunther receiving it. It was another week before he finally departed Berlin, on board a Luftwaffe transport plane carrying with it the famed soprano, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, and her entourage. She was to perform in London's newly rebuilt Opera House. Gunther spent the short flight making notes in his pocket book, for a screenplay he was vaguely thinking to write. He was not unduly concerned about Ulla. His view of women in general, and of actresses in particular, was that they were prone to exaggeration. No doubt Ulla's trouble would prove such as they'd always been—usually, he thought with a sigh, something to do with money. In that he was both right and wrong.

He was flattered, and glad, that she wanted to see him again. They had carried on a passionate love affair for several months, in Berlin in '43, before Gunther was sent to the Eastern Front, and Ulla went on to star in several well-received patriotic films, the pinnacle of which was Die große Liebe, for a time the highest-grossing film in all of Germany. Gunther had watched it in the hospital camp, while recovering from the wound which, even now, made him walk with a slight, almost unnoticeable limp. He only really felt it on very cold days, and the pangs in his leg brought with them memories of the hell that was the Eastern Front. He had never known such cold.

"Don't you see?" he said to me, much later. He was pacing my office, his hair unkempt for once, his eyes ringed black by lack of sleep. He'd lost much of his cool amused air by then. "Because we did it, we beat the Russians, and Ulla went on to star in Stalingrad, that Stemmle picture, but it was the last big film she did. I don't know what happened after that. We lost touch, though there'd always been rumors, you see."

He'd told me quite a lot by then but I was happy to let him talk. I knew some of the story by then and, of course, I'd known Miss Ulla Blau. We had been taking an interest in her activities for some time.

The plane landed at Northolt. There was no one there to welcome him and the soprano and her entourage were whisked away by my superior, Group Leader Pohl. I saw Gunther emerge into the terminal with that somewhat bewildered look that afflicts the visitor. He saw me and came over. "Where can a man get a taxi around here?" he said, in German.

"I'm afraid I don't . . ." I said, in English.

His eyes, surprisingly, lit up. "You are British?" he said.

"Yes. You speak English?"

"But of course." His accent was atrocious. "I learn to speak English in the cinema," he explained. "Do you know the works of Alfred Hitchcock?"

"His films are prohibited nowadays," I said, kindly. He frowned. I was not in uniform and he did not know what I was until later.

"Yes, yes," he said. "His death was most regrettable. He was a great maker of movies. I'm sorry," he said, "I have not introduced myself. Gunther Sloam." He extended his hand and I shook it.

"Name's Everly," I said. "I was in fact on my way back into town now. Can I give you a ride?" My jeep was outside.

"That would be most kind," he said. "I am here to see an old friend, you see. A woman. Yes, I have not seen her since the war." he laughed, a little sadly I thought. "I am older, perhaps she is older too, no? But not in my memory, never."

"You're a romantic," I said.

"I suppose," he said, dubiously. "Yes, I suppose I am."

"There is not much call for romantics in London," I said. "We English have become pragmatists, since the war ended."

He said nothing to that; perhaps he never even heard me. He sat beside me in the jeep as we went past the ruined buildings left over from the bombings, but I don't think he saw them, either.

"Where do you need to go?" I said.

"Soho."

"Are you sure? That is not a very good area."

"I think I can manage, Mr. Everly," he said. He lit a cigarette and passed one to me.

"Danke," I said. Then again in German, "And who is this mystery lady you're visiting, if you don't mind my prying?"

He laughed, delighted. "Your German is flawless!" he said.

"I studied in Berlin before the war."

"But that is wonderful," he said.

Then he spent fifteen minutes telling me all about Fräulein Ulla Blau; her film career; their passionate affair ("But we were both so young!"); his new screenplay ("A Western, in the Karl May tradition. You know how fond the Führer is of these things"); Berlin ("Have you been back? It's a beautiful city now, beautiful. Say what you want about Speer but the man is a gifted architect"); and so on and so on.

At one point I finally managed to interject. "And you know what your friend is doing these days?" I asked him.

He frowned. Such a thought had not entered his head. "I assumed she was acting again," he said. "But I hadn't really thought . . . Well, it is no matter. I shall find out soon enough."

We were driving along the Charing Cross Road by then. The few approved bookshops stood open, their wan light spilling onto the dark pavement outside. I remembered the book purges and burnings after the invasion—after all, I led one such group myself. I did not like doing it, yet it was a necessity of the time. Gunther did not seem to pay much attention. His eyes slid over the grimy frontage of the shops. "Where are your famed picture palaces?" he said. "I have long desired to ensconce myself in the luxuries of the Regal or the Ritz." His eyes shone with a childish enthusiasm.

"I'm afraid most were destroyed in the Blitz," I said apologetically.

He nodded. We were in Soho then, a squalid block of half-ruined buildings where the lowlifes of London made their abode. It was a hard place to police and patrol, filled with European émigrés of dubious loyalties. But it was useful, as such places inevitably are.

Along Shaftesbury Avenue, the few theatres were doing meager trade. The big show that year was Servant of Two Masters, an Italian comedy adapted to the English stage. It was showing at the Apollo. Dean Street itself was a dark thoroughfare that never quite slept. Business was conducted in the shadows, and red lights burned invitingly behind the second-floor windows. I saw doubt enter Gunther's eyes and I almost felt sorry for him. I had my own interest in his well-being or otherwise. My men were already stationed unobtrusively in the street.

"This is the place," I said, stopping the jeep. He stepped out and extended his hand.

"Thank you, Everly," he said. "You are a gentleman."

I could see he liked that word. The Germans are a peculiar people. Having won the war, they were almost apologetic about it. I said, "If your visit does not go well, there is a transport leaving for Berlin tomorrow night. I can ensure you have a seat on it."

His eyes changed; as though he were seeing me for the first time.

"You never said what you do," he said.

"No," I agreed. "Goodbye, Mr. Sloam."

I left him there. I did not expect him to be so much trouble as he turned out to be.