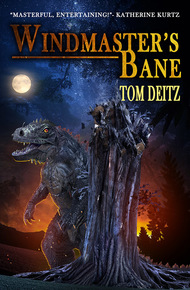

Tom Deitz grew up in Young Harris, Georgia, a small town not far from the fictitious Enotah County of Windmaster's Bane, and earned a Bachelor of Arts and Master of Arts degrees from the University of Georgia. His major in medieval English literature led Mr. Deitz to the Society for Creative Anachronism, which in turn generated a particular interest in heraldry, historic costuming, castle architecture, British folk music, and all things Celtic. In Windmaster's Bane, his first published novel, Tom Deitz began the story of David Sullivan and his friends, a tale continued in Fireshaper's Doom and more books in the series. He won a Georgia Author of the Year award for his work and a Lifetime Phoenix Award from Southern fans. In addition to his writing, in private life a self-confessed car nut, Tom was also a popular professor of English at Gainesville State College (today the Gainesville campus of the University of North Georgia), where he was awarded the Faculty Member of the Year award for 2008. On the day after his birthday in 2009, he suffered a massive heart attack and in April of that year he passed away at the age of 57. Though he was never able to realize his dream of owning a small castle in Ireland, Tom had visited that country, which he loved, and at the time when he was stricken with the heart attack he was in the planning stages for a Study Abroad trip to Ireland that he would have led. The trip took place, and some of Tom's teaching colleagues scattered his ashes in a faery circle.

RIDDLE, RING, AND QUEST

In Georgia's Blue Ridge Mountains, tales are told of strange lights, of mysterious roads…of wondrous folk from enchanted realms. All these are hidden from mortal men, and those who have the gift to look on them are both blessed and doomed…

THE WINDMASTER

Young David Sullivan never dreamed that the myths of marvels and magic he loved were real. But in his blood was the gift of Second Sight. And near his family's rural farm lay an invisible track between worlds…where he would soon become a pawn in the power game of the Windmaster, an evil usurper among those the Celts called the Sidhe. David's only protection would be a riddle's answer and an enchanted ring…as he began his odyssey of danger into things unknowing and unknown…

I first read Windmaster's Bane years ago when I was in college, and loved it so much I immediately bought every other book by Tom Deitz. Unfortunately for me, he was still writing this series at the time, so I had to wait (impatiently!) for each book to come out. :) Tom's faeries, the Sidhe, come across as magical, intriguing, and different from mortals, yet at the same time feel very, very real. I love this book, and am thrilled to be able to include this book in this bundle. – Jamie Ferguson

They ran down the long slope of hill, stopping at the irregular barrier of blackberry briars that fringed the bank above the cornfield. All at once the music was louder; David thought he could make out the jingle of bells and what almost sounded like voices singing. He screwed up his eyes until they hurt, staring vainly into the darkness in search of he knew not what.

And then—at the far side of that part of the field which lay beyond the highway—he saw…something: a file of pale yellow lights, winking in and out among the trees which bordered the small stream that marked the property line maybe an eighth of a mile away.

David inhaled sharply.

Little Billy stared up at him quizzically.

"Can you see anything, Little Billy?" he whispered.

Little Billy squinted into the gloom. "I can see a buncha lightnin' bugs flyin' along in a line over by the creek. Is that what you're talkin' about? Makes my eyes hurt. An' I can sorta hear some kinda singin' too." His voice trembled ever so slightly.

"Come on, then, let's take a closer look."

Little Billy hung back a moment, doubt a shadow among shadows on his face, but followed dutifully as his brother pushed through the briars, careful of the tiny thorns. They scooted down the clay slope and slipped into the welcome cover of the towering corn. As they thrust their way between the knobby stalks, the hard-edged leaves cut at their exposed skin like green knives. Finally they shouldered through the last row and crouched breathlessly among the weeds and beer cans in the shallow ditch just below the shoulder of the highway.

David eased himself up cautiously.

Pain filled his eyes of a sudden. Pain—or light, he could not tell which—subsiding as quickly as it had come into an itching so intense that he wrenched off his glasses and rubbed his lids furiously.

When he looked up again, the lights were closer, brighter, following the line of the highway but a little way back from it, angling gradually toward a point farther to the right where the road and the fields and the mountain all converged.

"They're heading for the woods behind our house—toward that old Indian trail Uncle Dale was talking about, I bet! Quick, maybe we can get a better view from up there. Come on!"

David ducked back into the cornfield with Little Billy following reluctantly behind. Together they loped along between the last row and the bank, gradually drawing ahead of the lights that were fast approaching the highway to their left. Finally they halted at the base of a steeper, rockier slope above which the forest began in truth. A barricade of young maple trees and more blackberry briars marked its edge, except at one place further on where a dark gap showed in the leafy barrier—almost like an archway.

David hesitated, unsure, feeling somehow wary of the gap. He glanced back, saw the lights still approaching, brighter and brighter, and made his decision.

"Up the bank, Little Billy. Quick."

Little Billy grabbed David's pant leg. "You go, I don't wanna. I'm scared."

David grasped his brother roughly by the shoulders. "You want me to leave you alone in this cornfield in the middle of the night?" The harshness of the words surprised both of them.

Little Billy stared at the ground. "No, Davy."

"Then shinny up that bank!"

Little Billy set his chin. "You first."

David frowned. "No running off?"

"Promise."

David scrambled up the bank, pausing before the thorny barrier at the top to hoist his brother the final few feet. The briars were thicker than they had first appeared, but he kicked recklessly through them and entered the forest, directly above the sharp curve where the highway bent squarely east and began its torturous climb up to Franks Gap. They were only about a quarter mile from home, so David knew he must have been in that place before, but in the bright moonlight of the summer night it seemed different somehow, as if transfigured by that light. Transfigured—or maybe damned: The thought was a flickering ghost in David's mind as he glanced around, saw the familiar trunks of pines and maples, the dark clumps of rhododendron and laurel. And the briars—more briars than he had ever seen, weaving in and out among the trees to the right, forming a subtle prickly barrier between himself and the house whose blue light he could dimly discern like a distant will-o'-the-wisp.

But to his left the ground was clearer and he could see that there was a sort of trail coming on straight up between the trees like a continuation of the line of highway. It was covered with moss and pine needles, but nothing else grew there. Indeed, it was that lack of growth that most clearly delineated it, David decided, though now he examined it closely, it appeared overlaid by a ribbonlike glaze of golden luminescence that did not quite seem to lie upon the ground. He almost thought he could make out patterns forming and reforming along that nebulous surface. But looking at it made the tingle in his eyes become almost painful, and he felt a strange reluctance to walk there. Instead, he dragged Little Billy along beside it until their way was blocked maybe a hundred yards up the mountain by the half-rotted trunk of a fallen tree.

David sat down on the log, pulling his brother down next to him. And then realization struck him like a blow: There could be no moonlight, for the moon had been full two weeks ago. Why, just the night before he had remarked to Alec about it being dark of the moon. Yet there was the same kind of cold, sourceless brightness in that place, like a snowfield seen in starlight—everywhere but on the trail itself. A shiver ran up his spine. The lights…the moon…the briars…this place…

Something was very wrong.

But at that moment a whisper of music reached his ears, and the first yellow lights became visible at the top of the bank.

His eyes felt as if they were on fire; his vision sharpened, blurred, sharpened again. He discovered that he was sweating, too, could feel the short hairs on the back of his neck rise one by one as more and more of the lights entered the forest, increasing in intensity and size as they came, coalescing finally into a nimbus of golden light that enfolded in its heart…

People.

If people they were: a great host of stern-faced men and women riding as if in solemn procession astride great black or white horses, or horses whose smooth hides gleamed like polished steel or burnished copper or new-wrought gold. One or two of those steeds appeared to be scaled, and many sported fantastic horns or antlers, though whether these grew from the beasts themselves or were some work of artifice David could not tell.

But it was the appearance of the riders that made David's mouth fall open in wonder, for he had never witnessed such a display of color and texture and form as now passed before him like a dream from another age.

They were a tall people—both men and women—and beautiful: slim of build, narrow of chin, slanted of brow, with long, shining hair, most frequently black, and flashing eyes that seemed at once menacing and remote.

Long, jewel-toned gowns of a heavy napped fabric like velvet accentuated the proud carriage of most of the women, though here and there rode one clad in strangely cut garb patterned in elaborate plaids or checks. The majority of the men wore long hose and short, tight tunics with flowing sleeves, but an occasional one was dressed in a longer robe or in clothing of a much simpler, looser style and rougher texture. A few members of both sexes wore glittering mail or plate armor. Tassels and jewels and feathers and fringes were everywhere; and here and there was the glint of shiny metal blades and golden crowns. The host had stopped singing now, but from the bells on their clothing and their horse trappings rang out a gentle, constant melody, taking its rhythm from their tread.

At their head rode a man clad in silver armor wrought of overlapping ridged plates like fishes' scales, each one rayed with a blazing filigree of golden wire. His eyes were the color of deep still water, and the long fair hair that flowed like silk from beneath a plain silver circlet shone like the sun. He sat astride a long-limbed white stallion and bore a naked sword across the saddle before him. A white cloak swept from his shoulders, its golden fringe rippling about his ankles. The light came strongest from him.