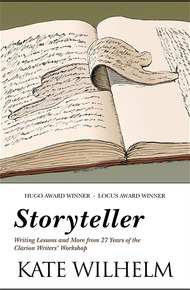

Kate Wilhelm (1928-2018), was the author of more than thirty novels including Where Late the Sweet Bird Sang andThe Unbidden Truth. Her work was adapted for TV and film and translated into twenty languages. Her work was awarded the Prix Apollo, Kurd Lasswitz, Hugo, Nebula, and Locus Awards, and she was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame. Her short fiction appeared in landmark anthologies such as Again Dangerous Visions, Orbit, The Penguin Book of Modern Fantasy by Women, and The Norton Book of Science Fiction.

For 27 years, Kate Wilhelm and her husband, Damon Knight, taught at the Clarion Writers' Workshop, an intensive and ambitious six-week writing program for novice writers, known to participants as "boot camp for writers."

Part memoir and part writing manual, Storyteller is Wilhelm's affectionate account of the history of the program and her years there with Damon as mentors and instructors. She relates how Clarion began, explains why workshop participants fear red pencils* and rejoice at the sight of water guns, what she learned, and how she passed a love of the written word on to generations of writers. Storyteller is a gift to all writers from this generous and acclaimed teacher. It includes a special section of writing exercises and advice.

"There are many books of writing instruction out there, but what sets Storyteller apart is the sense that Wilhelm really knows students and knows how to teach them to craft a professional story."

– The Oregonion"A useful, compact, and entertaining guide to writing that is neither bound to a particular genre or market."

– Locus"Teaching writing is a balancing act between compassionate encouragement and firm, blunt criticism. Kate is a master of it. The book uses reminisces about the founding, development and running of Clarion to frame a series of practical, plainly stated lessons for the beginning (and professional) writer. I learned a great deal reading it — something that can be accomplished in a deceptively short time, for Kate is also a master of simply and clearly setting out complicated, muddy issues, a skill honed both in her award-winning fiction (Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang is a personal favorite) and in her long years of teaching."

– Cory Doctorow, BoingBoing"This book should be on the reference shelf of every aspiring writer. Not only is it a gift of insight and experience of a wonderful writer but it's also a fine story of the growth of a renowned writing workshop. Highly recommended."

– SF RevuMy Silent Partner

I don't live by the clock. I work late hours at night and get up when I wake without much regard for what time it is. On those occasions when I have to get up early and set the alarm at bedtime, I invariably wake before it goes off. I know many others who say the same thing happens to them. It is as if something in us is keeping track of the time while we sleep.

Most of us have had the experience of seeing a familiar person approach, only to find to our dismay that her name has slipped out of memory. Embarrassing, but common. We cover ourselves as best we can and move on, then have the name pop up an hour later, or the next morning, or perhaps just minutes later.

Or you sniff anise and find yourself deluged by memories from childhood of Christmas cookies baking, something you have not thought of in years perhaps.

If you have a real problem that you have been mulling over for a long time and still can't solve we all know to sleep on it and in the morning you have your answer. Many scientific discoveries have been made in such a way. First you give the problem your full attention, immerse yourself in it, then put it aside, and the answer comes to you.

We are going to skip the entire, ever-controversial, never-ending argument over mind/body, conscious/unconscious, rationalism/Jungian psychology, right brain/left brain distinctions, and all other theoretical and philosophical explanations. We will also skip physiology, synapses formation, neural pathways, and such and talk about direct experience.

For the sake of this section when I refer to you, I mean that thinking, verbal person who writes and talks and is reading this passage. I don't mean that other part of your psyche whose form of communication is through images, dreams, impulses, impressions without form, that other part that remains wordless and may, furthermore, fail to recognize your words. For the sake of this section I'll consider it as another being, separate from you, even if forever united with you. Damon referred to that other part as Fred, but I don't think there is a Fred living in my brain. I think of it as my silent partner, or SP.

SP is like an overworked file clerk scurrying around in your psyche taking care of things, feeding you the right file on call, nudging you to remember an appointment, filling in the blanks of your memory—sometimes belatedly, but more often faithfully—giving you dreams about every ninety minutes throughout sleep, furnishing your daydreams with images, and so on.

You want to arrive at a good working relationship with that silent partner. For one thing, SP has complete access to your entire database that is made up of everything you have experienced in your whole life, and you will need SP's help more often than you realize. For another you cannot produce art without it. You could fill in the blanks of a complete outline and have what might look like a story, but it would have the same relationship to literary art as painting-by-numbers does to visual art. The finished work might show skill in following an outline, flawless grammar, good deliberately-chosen words, but it would be mechanical and empty. And finally, you must cultivate SP because it is a wonderful problem solver and collaborator.

Although SP has found ways to communicate with you, you can never be certain you can communicate to SP. It does not use language, words, to communicate with you, and from all indications it does not comprehend words you direct at it or, at least, it does not respond in a meaningful way to your direct-orders or pleas expressed in words. It is aware of you and everything you do instant by instant, but you are never aware of it directly, only the effects it has on you. Even if it seems that two-way communication is impossible, with reflection it becomes obvious that it does grasp yes or no, acceptance or rejection.

Start with habituation. Say you have made the decision to put aside two hours three days a week and declare that time yours, your time to write. You go wherever you can write and work at it. If you are not actively writing a story, rewrite an old one, or analyze something you did in the past or someone else's work to see how that person did it. Dedicate that time to writing and nothing else, and keep doing it on schedule. If you are faithful to your own timetable, the day will come when, if you yield to the temptation to watch a show on television or play cards, or do something else, you may begin to feel uncomfortable, your mind may wander, or you may become restless. SP is signaling that this is your writing time. If you yield often and ignore the signals, SP stops reminding you. If you recognize the signal and go back to work, SP will remind you a little more forcefully the next time you yield. Recognizing the signal does not mean you are aware of it necessarily. What you may be aware of is that you are uncomfortable, and when you go to work, your discomfort is eased, but that is enough. Accepted signals get stronger; ignored signals fade out.

You have nothing to worry about if you get no such signals while on vacation, traveling, having in-laws visit, or any of the other events that interrupt your daily routine. It appears that SP grants time off for such events in your life, and the signals either are not sent, or are too feeble to register. When the routine is reentered later, they return.

Probably all your life you have imagined snippets of stories, possible scenes, situations, glimpses of characters, story ideas, images and have done little or nothing with them. Most writers have very active daydreams for years before they actually begin to write. When you begin to accept the ideas, snippets and all, and work or play with them, manipulate them, more will follow and they will become stronger and more compelling. Your silent partner's offering has been accepted. You have communicated through acceptance. It is as if your acceptance has empowered it, and the next time it will be more forceful.

Your silent partner is amoral, it has no real esthetic sense, no chronological sense, no relative worth sense; a pebble is as good as a pearl to it. Also it does not know anything you have not taught it through your life experiences. If you read widely in a variety of subjects, it has a wealth of materials to offer back to you, often in strange and wonderful new combinations that you might never have considered. If your reading consists of only one or two favorite writers, it has that as its source material. If you read little or nothing, just watch television, for example, that content makes up much of its database. If it offers trivia and you accept and write that, it will offer more of the same invariably.

This is where the partnership comes in. You have to examine the ideas that seemingly come from out of nowhere, and actually are from your silent partner, and say yes or no to them. This requires the rational, verbal, conscious you. You can't tell SP directly what you want; you can demonstrate what you don't want by your rejection, or signify what you find exciting, or perhaps simply worthwhile, by your acceptance. You are not born with the skill to know which ideas are worthy of writing, which are too trivial to bother with; that judgment takes time and patience as your own critical faculties are honed and developed, but you will find that as you become more demanding of yourself, the material you receive from SP—impulses, ideas, images, sequences, whatever form it takes—will become more complex and interesting.

Probably you will also find that one day when you have been working, writing well, feeling good about it, if you are interrupted, or when it is time to stop, you will feel that you have been gone. You have been somewhere else, in some kind of alternate head space, that someone else has been filling in for you. Perhaps your sense of time has been distorted; it is hard to believe that three hours have passed. Or perhaps the headache you had earlier was forgotten, then returns when you leave your work. Or a nagging worry was put aside and now surges back.

I have often said that I, this person who does the shopping and gardening and attends to the daily chores that arise, I am not the one who writes my stories. That is my writing persona, the person I become when I am writing. She is much smarter than I am, and she has a memory I wish I had available all the time. She can use words I cannot even pronounce. She seems oblivious to minor aches and pains, and she is disdainful of the clock.

Every summer at the six-week Clarion Writers Workshop, the visiting instructors give a reading, sometimes to the public, sometimes just for the students. One year the story I read was about a young woman who has never reconciled with her own childhood of humiliation and pain caused by a brutal father. Now, in love with a man who wants to marry her, she can't make up her mind. At a family celebration, she confronts her father and her brother, who was beaten into submission and is now doing the same thing to his child. The father is a man of wealth and influence, a lawyer, and her brother is following in his footsteps. They are people of substance, highly regarded in the community. She dreams that she is in a silent walled garden trying desperately to reach doors that are closing. She fails to get to them before they close all the way and she is imprisoned in an eerily silent garden with no escape. When she wakes from her dream she flees her father's house, drives aimlessly, and finally stops at a motel where she at last reaches for the phone to call the child services agency to report her brother. The story ended there.

The title of the story was "The Great Doors of Silence," published in Redbook Magazine. Glenn Wright, the program director, asked the students if her call would save the child. There was no clear answer because I had not given one in the story. Then Glenn said, "Well, of course not. Her name is Cass. She's Cassandra crying in the wilderness."

I had not known that. The name had come to me and I had used it without another thought, but my writing persona had known and made use of it. More recently I named a character Erica, and in the course of the novel she acquired the nickname of Rikki, and again my writing persona had helped. Her name "just came" to me. Rikki Tikki Tavi of Rudyard Kipling fame was fearless and deadly protecting his own.

I have a pretty good working relationship with my own silent partner. I like being in that alternate state of awareness when my writing persona takes over. I think that in that state the gap between you and your silent partner closes, if not altogether, then much of the way. It is exhilarating to use your whole brain, or even simply most of it.

But you have to work with it, work on it, and the first step may be habituation, your recognition of signals and signs and your acceptance or rejection of them, then your acceptance or rejection of images, snatches of memory, even sequences that are dreamlike and surreal. They may be very beautiful or they may be frightening, but they are not stories as given.

Your silent partner cannot write stories. It is nonverbal and nonrational. It cannot organize the wealth of dream material and memories at its disposal into a series of happenings that make sense. In a sleeping dream or even in a waking daydream, you may be euphoric one moment with the sensation of floating, flying, deliriously happy, and in the next moment plunging to earth in terror. Both apparently are universal dreams. Both are loaded with emotion and power, but they do not make a story. Your very rational mind has to manipulate them, find cause and effect, find a character who can express that joy or fear in a plausible way.

Often beginning writers recognize the power of this material and are afraid to change it, to manipulate it in any way, and instead try to translate it directly from dream imagery to waking actions. It rarely will work as a direct translation.

I urged students to treat this rich material the same way they would treat the results of research. Use what you need of it, change what you must change, and don't treat it as untouchable. It is a gift from you to you and it is the nature of gifts that once proffered and accepted they become the property of the receiver to do with as she pleases.

Your silent partner can give you vivid, powerful, nonverbal material, but it cannot tell you what to do with it, how to use it in stories. It cannot tell you what the sequences and images mean. That takes a conscious, rational mind; it takes technique and control deliberately applied. You may find that some of the images and fragments are frightening when you examine them closely and accept the meaning you derive from them. Things you would never admit to, desires you have to deny, fears you can't express, but that's what lies at the heart of good fiction. Your readers have the same problems expressing those things, and through fiction they are afforded the opportunity to experience them indirectly and maintain personal safety. This can be cathartic for writer and reader alike.

To become a successful writer you must cultivate the partnership between that nonverbal wealth of emotional material, and your own consciously applied control of it, and the sooner the better. Without it your stories will be flat and mechanical, and quite likely they will be trivial and unpublished. With it, when you begin to examine this material and express it through your characters in meaningful ways, your stories will become richer, with much greater depth, and possibly approach the universality that writers strive for.