Lance Olsen is author of more than 25 books of and about innovative writing, including, most recently, the novels Dreamlives of Debris (Dzanc, 2017) and My Red Heaven (Dzanc, forthcoming 2020). His short stories, essays, and reviews have appeared in hundreds of journals and anthologies, such as Conjunctions, Black Warrior Review, Fiction International, Village Voice, BOMB, McSweeney's, and Best American Non-Required Reading. A Guggenheim, Berlin Prize, D.A.A.D. Artist-in-Berlin Residency, Pushcart Prize, and two-time N.E.A. Fellowship recipient, as well as a Fulbright Scholar (Finland), he teaches experimental narrative theory and practice at the University of Utah.

Trevor Dodge's work has appeared in publications such as The Butter, Little Fiction, CHEAP POP, Juked, Hobart, Gobshite Quarterly, Metazen, Western Humanities Review, and Golden Handcuffs Review. He is author of three collections of short fiction, most recently The Laws of Average (Widow + Orphan, 2016) and He Always Still Tastes Like Dynamite (Subito, 2017).

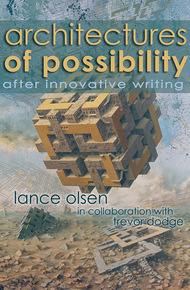

Ideal for individual or classroom use, Architectures of Possibility theorizes and questions the often unconscious assumptions behind such traditional writing gestures as temporality, scene, and characterization; offers various suggestions for generating writing that resists, rethinks, and/or expands the very notion of narrativity; visits a number of important concerns/trends/ obsessions in current writing (both on the page and off); discusses marketplace (ir)realities; hones critical reading and manuscript editing capabilities; and strengthens problem-solving muscles from brainstorming to literary activism.

Exercises and supplemental reading lists challenge authors to push their work into self-aware and surprising territory.

In addition, Architectures of Possibility features something entirely lacking in most books about creative writing: more than 40 interviews with contemporary innovative authors, editors, and publishers (including Robert Coover, Lydia Davis, Brian Evenson, Shelley Jackson, Ben Marcus, Carole Maso, Scott McCloud, Steve Tomasula, Deb Olin Unferth, Joe Wenderoth, and Lidia Yuknavitch) working in diverse media, providing significant insights into the multifaceted worlds of experimental writers' writing.

"Architectures of Possibility opens up fiction to a possibility that 'gives us more life, extends and validates the range of what it means to be a human' in the twenty-first century … [A] wonderful book on innovation and fiction[.]"

– American Book Review"In the midst of reading this book and its possibilities and their usefulnesses, you think that to finish reading this book and then to try to write something with it "in mind" is to try to type while also holding up each point of light in the night sky with your fingertips. Even worse, you think, each of these "things" in this "book" is not a single morsel to be consumed, not a nugget of gold worth its shine, but rather a seed planted, or worse yet, not a seed but a sac, millionfull of spores, celestial bodies of fire, dispersed, inhaled. You are overwhelmed."

– Altered States"This is a book that any writer could have on her shelves and pick up again and again. Architectures of Possibility doesn't ask writers to work towards some impossibly ideal text, but to resist, question, fail, re-build, proceed, and return."

– Quarterly West"I am…crowning Lance Olsen's book as the single best advisory to writers I have ever encountered. This is an absolutely masterful text."

– By The Book Reviewspossibility spaces

Carefully follow what most textbooks on fiction tell you, and chances are you will end up producing a well-crafted piece that could have been produced just as easily in 1830.

You will end up producing, that is, a narrative where language is transparent and focus falls on your protagonist's psychology. That protagonist will be rounded, resonant, believable, and usually middle or lower-middle class. Your setting will be urban or suburban and rendered with the precision of a photograph, while the form your narrative takes will be so predictable, so patterned by convention, as to be virtually invisible: it will have a beginning, a muddle, and an ending through which your character will travel in order to learn something about himself, herself, or his or her relationship to society or nature.

You will end up producing some version of realism, in other words, and realism is a genre of averages—a genre about middle-of-the-road people living on Main Street in Middletown, Middle America.

In For a New Novel, Alain Robbe-Grillet calls this sort of writing the Balzacian Mode because in a sense its impulse stems from the early nineteenth-century work of Honoré de Balzac, although it could just as well be called the Defoean Mode—after Daniel Defoe and his 1719 puritanically detailed pseudo-reportage of Robinson Crusoe's daily accomplishments on his famous island. (Revealingly, Crusoe's first inclination after finding himself shipwrecked is to recreate as closely as possible a bourgeois European enclave…another kind of Main Street.)

Such fiction, according to Ian Watt, appeared in the eighteenth century with the rise of the new middle class in England and on the Continent. Rooted in the journalism, diaries, letters, and personal journals of the time, it is the stuff of Richardson and Fielding and their literary offspring: Flaubert and Chekhov, Ann Beattie and John Updike, Amy Tan and Jonathan Franzen. It represents a way of perceiving influenced by rationalist philosophers like Locke and Descartes that embrace a pragmatic, empirical understanding of the universe that emphasizes individual experience and consciousness.

Samuel R. Delany once pointed out those sorts of fictions aren't written for readers in, say, New York, where all the mega-publishing houses and slick magazines reside in the U.S., but for a certain imagined housewife living in a small-yet-comfortable house somewhere in Nebraska. If there's nothing in a given narrative she can relate to, nothing and no one she wants to know something about, then that narrative is out of luck so far as that publishing world goes.

"The housewife in Nebraska has, of course, a male counterpart," Delany continues. "In commercial terms, he's only about a third as important as she is. The basic model for the novel reader has traditionally been female since the time of Richardson. But the male counterpart's good opinion is considered far more prestigious. He's a high school English teacher in Montana who hikes for a hobby on weekends and has some military service behind him. He despises the housewife—though reputedly she wants to have an affair with him.…Between them, that Nebraska housewife and that Montana English teacher tyrannized mid-century American fiction."

One reason that virtual couple responds to the Balzacian Mode so positively, Fredric Jameson argues, is that it "persuades us in a concrete fashion that human actions, human life is somehow a complete, interlocking whole, a single formed, meaningful substance.…Our satisfaction with the completeness of plot is therefore a kind of satisfaction with society as well."

What Jameson proposes, in essence, is that meaning carries meaning, but structuration carries meaning, too. The way you shape—or, perhaps more productively, misshape—a narrative means. Another way of saying this: every narrative strategy implies political and metaphysical ones—whether or not the author happens to be aware of the fact.

Creative writing is nothing if not a series of choices, and to write one way rather than another is to convey, not simply an aesthetics, but a course of thinking, a course of being in the world, that privileges one approach to "reality" over another.

Given the Heraclitean techno-global, multi-cultural, multi-gendered, multi-genred pluriverse our fluid selves navigate, the question thereby becomes: is the Balzacian Mode the most useful choice for capturing what it feels like to be alive here, now, in the midst of the twenty-first century?

Many of us no longer intuit existence is necessarily meaningful, if we ever did, and most of us certainly aren't satisfied with society, so why should we write as if we do and are?

Shouldn't our task as authors rather be to explore approaches to creativity that accurately reflect our own sense of lived experience?

If so, what might those approaches look like?

"If you don't use your own imagination," Ronald Sukenick once wrote, "somebody else is going to use it for you." This book intends to be a continual reminder of Sukenick's assertion, an invitation to conceive of writing as a possibility space where everything can and should be considered, attempted, and troubled. If success is defined as publication by a big publishing house or magazine, by joining the ranks of what Raymond Federman referred to as corporate authors, then this book is after the opposite. It believes that pushing as close to "failure" as you can in your work opens up myriad options you simply can't imagine while adopting conventional methods of narrativity.

Architectures of Possibility is all about taking chances, trying to compose in alternative, surprising, revelatory directions, about trying to move out of your comfort zone to discover what might lie on the other side.

Samuel Beckett: "Try again. Fail again. Fail better."

What follows is an extended proposal to think about where we are in space and time, to ask how each of us might most effectively capture that place and point in our own writing. Behind that proposal lies the assumption that writers work in a post-genre culture where there is no longer a significant difference between prose and poetry, between fiction and nonfiction. Theory, it takes for granted, is a form of spiritual autobiography, while all writing is always-already a kind of theorizing.

Architectures of Possibility doesn't intend to be a how-to text in the same way, for instance, Janet Burroway's Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft intends to be one. Her guide and the profusion like it are designed to instruct writers how to construct in the Balzacian Mode. This one is designed to encourage writers to investigate various ways of re-imagining what creative writing is and can be, and how, and why.

Writing is a manner of reading. It is a mode of engaging with other texts in the world, which itself is a kind of text. And reading is a manner of writing, interpretation, meaning-making. Which is to say that writing and reading are variants of the same activity. Existence comes to us in bright, disconnected splinters of experience. We narrativize those splinters so our lives feel as if they make sense—as if they possess things like beginnings, muddles, ends, and reasons. The word narrative is ultimately derived, through the Latin narrare, from the Proto-Indo-European root gno-, which comes into our language as the verb to know. At some profoundly deep stratum, we conceptualize narrative as a means of understanding, of creating cosmos out of chaos.

Yet in many cultural loci these days we are asked to read and write easier, more naively, less rigorously. We are asked to understand by not taking the time and energy to understand. One difference between art and entertainment has to do with the speed of perception. Art deliberately slows and complicates reading, hearing, and/or viewing so that we are challenged to re-think and re-feel form and experience. Entertainment deliberately accelerates and simplifies them so we don't have to think about or feel very much of anything at all except, maybe, the adrenalin rush before spectacle.

Although, obviously, there can be a wide array of gradations between the former and latter, in their starkest articulation we are talking about the distance between David Foster Wallace's Infinite Jest and Dan Brown's The Lost Symbol; between David Lynch's Lost Highway and Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen.

In The Middle Mind, Curtis White contends that the stories generated and sustained by the American political system, entertainment industry, and academic trade have helped teach us over the last half century or so by their insidious simplicity, plainness, and ubiquity how not to think for ourselves. Little needs to be said about how the political narratives of the United States have led, as White says, to the "starkest and most deadly" poverty of imagination, nor about how, "on the whole, our entertainment…is a testament to our ability and willingness to endure boredom…and pay for it." A little should be said, however, about White's take on the consequences of this dissemination of corporate consciousness throughout academia.

For White, the contemporary university "shares with the entertainment industry its simple institutional inertia"; "so-called dominant 'critical paradigms' tend to stabilize in much the same way that assumptions about 'consumer demand' make television programming predictable." If, to put it somewhat differently, student-shoppers want to talk about Spider-Man, Stephen King, and hip-hop in the classroom, well, that's just what they're going to get to talk about, since that's how English departments fill seats, and filling seats is how they make money, and making money is what it's all about…isn't it?

The result, White continues—particularly in the wake of Cultural Studies—has been the tendency to eschew close, meticulous engagement with the page; to search texts "for symptoms supporting the sociopolitical or theoretical template of the critic"; to flatten out distinctions between, say, the value of studying James Joyce, Lydia Davis, and Ben Marcus, on the one hand, and Britney Spears, The Bachelorette, and that feisty gang from South Park, on the other—and therefore unknowingly to embrace and maintain the very globalized corporate culture that Cultural Studies claims to critique.

Architectures of Possibility advocates a practice of writing and reading against simplicity, renewing the Difficult Imagination—that dense space in which we are asked continuously to envision the text of the text, the text of our lives, and the text of the world other than they are, and thus contemplate the idea of fundamental change in all three.

In other words, The Difficult Imagination is an area of impeded accessibility essential for human freedom where we discover the perpetual manifestation of Nietzsche's notion of the unconditional, Derrida's of a privileged instability, Viktor Shklovsky's ambition for art and Martin Heidegger's for philosophy: the return, through complexity and challenge (not predictability and ease) to attention and contemplation.

"The technique of art," Shklovsky urged, "is to make objects 'unfamiliar,' to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception."

For Roland Barthes: "Literature is the question minus the answer."

In light of its natureless nature, writing of the Difficult Imagination will always make us feel a little foolish, a little tongue-tied, before an example of it. We will find ourselves standing there in a kind of baffled wonder that will insist upon a slightly new method of apprehending, a slightly new means of speaking, to capture what it is we have just witnessed.

Take, by way of illustration, J. M. Coetzee's Elizabeth Costello, which commences by telling the life and obsessions of a contemporary writer in her late sixties by means of a series of lectures she gives and attends. It begins, that is to say, in the realm of the Balzacian Mode, but a version faintly tweaked, askew, both by means of its structuring principle (those lectures, versions of which Coetzee actually delivered) and by a disquietingly flat prose style and series of odd narratorial insertions (the passage of weeks, months, or years, for example, is covered by the abrupt phrase: "We skip").

In the seventh of eight chapters, as the reader has come to feel settled into these conventions, the novel unexpectedly leaves the universe of logical mimesis and Freudian depth-psychology behind and veers first into a highly textured meditation, still from the protagonist's point of view (although her presence drops back decidedly from it, and symbol starts swamping personhood) about the relationship between gods and mortals in a variety of mythological iterations, and next, in the final chapter, into a retelling of Kafka's parable "Before the Law," in which Elizabeth rather than Kakfa's man from the country seeks entrance in vain, not from the quotidian world into the law, but from a purgatorial in-between place into some beyond-region—possibly heaven itself.

Coetzee's text ends with a brief, cryptic postscript that takes the form of an epistle from another (or is it somehow the same?) "Elizabeth C." (Elizabeth, Lady Chandos), this one quite possibly on the verge of madness, written on 9/11…not in 2001, as we might expect, but in 1603, the year the English Renaissance begins its concluding with the death of Elizabeth I.

With that, everything we have just read drifts into suspension. Is the narrative supposed to add up to the hallucinations of a seventeenth-century woman? A twentieth-first-century woman imagining from beyond the grave, or on her way to it? A serious postulation of cyclical rebirth or eternal recurrence? An ironic one? Or, more likely, a text not about character and mimesis at all, but rather about a series of philosophical problems, an investigation into a novel ripped open as unpredictably as our culture was on that glistery blue September day in 2001, a universe and a universe of discourse exploring the conditions of their own self-perplexing existence?

Writing of the Difficult Imagination asserts that language, ideas, and experience are profoundly, joyously complicated things, or, as Brian Evenson comments: "Good fiction, I would argue, always poses problems—ethical, linguistic, epistemological, ontological—and writers and readers, I believe, should be willing to draw on everything around them to pose tentative answers to these problems and, by way of them, pose problems of their own.…It is our ability as [innovative] writers to stay curious, to borrow, to bricoler, to adapt and move on, that keeps us from becoming stale."

Staging the Difficult Imagination is, of course, an in-progress futile project—and an in-progress indispensable one. Its purpose is never a change, but a changing, an unending profiting from the possibility space of the impossible, from using our marginal status as innovationists to find an optic through which we can re-involve ourselves with the world, history, and technique, present ourselves as a constant prompt to ourselves and to others that things can always be different, more intriguing, than they seem.

Any such changing will occur—if it occurs at all—locally. That is, writing of the Difficult Imagination won't generate macro-revolutions. Rather it will generate a necklace of micro-ones daily: nearly imperceptible, nearly ahistorical clicks in consciousness that come when you make or meet an explosive, puzzling, challenging, enlightening writing thought experiment.

reading suggestions

Barth, John. "The Literature of Exhaustion" (1967) and "The Literature of Replenishment" (1979). Two cornerstone essays on the innovative by one of the most influential experimental authors of the second half of the twentieth century. The first focuses on the death of old forms of fiction, the second on fiction's postmodern reinvigoration.

Berry, R. M. and Jeffrey Di Leo, eds. Fiction's Present: Situating Contemporary Narrative Innovation (2007). Essays by such contemporary writers as Percival Everett, Michael Martone, Carole Maso, Joseph McElroy, Leslie Scalapino, and Lidia Yuknavitch on innovation's history and current problematics.

Federman, Raymond. "Surfiction: A Postmodern Position" (1973). "The only kind of fiction that still means something today," this key essay asserts, "is the kind of fiction that tries to explore the possibilities of fiction beyond its own limitations; the kind of fiction that challenges the tradition that governs it."

Marcus, Ben. "Why Experimental Fiction Threatens to Destroy Publishing, Jonathan Franzen, and Life as We Know It" (2005). Provocative explanation and defense of experimental writing in contemporary America that argues, in part, "the true elitists in the literary world are the ones who have become annoyed by literary ambition in any form."

McKeon, Michael, ed. Theory of the Novel (2000). An extraordinary compendium of narrative theories, including excerpts from Fredric Jameson's The Political Unconscious, Alain Robbe-Grillet's For a New Novel, and Ian Watt's Rise of the Novel.

exercise

Bring in to your writing community a short passage from one of your favorite writers of all time, and from one of your least favorite. Be prepared to explain why each affects you the way it does, paying close attention to style, voice, ear, form, character, and imaginative flair. What would you like to steal from the first? What can you learn by negative example from the second? What does each tell you about your aesthetic preferences? How do the aesthetics of each imply a politics, a metaphysics? How, if at all, do they, as Barthes suggests, provide the question minus the answer?

* * *