Freelance writer, novelist, award-winning screenwriter, editor, poker player, poet, biker, Travis Heermann is a graduate of the Odyssey Writing Workshop, an Active member of SFWA and the HWA, and the author of the Tokyo Blood Magic, The Hammer Falls, The Ronin Trilogy, and other novels. His more than thirty short stories appear in Baen Books' anthology Straight Outta Deadwood, plus Apex Magazine, Tales to Terrify, Fiction River, Cemetery Dance's Shivers VII, and others. As a freelance writer, he has contributed a metric ton of work to such game properties as Firefly Roleplaying Game, Legend of Five Rings, EVE Online, and BattleTech, for which he's been nominated for a Scribe Award.

He enjoys cycling, collecting martial arts styles and belts, torturing young minds with otherworldly ideas, and monsters of every flavor, especially those with a soft, creamy center.

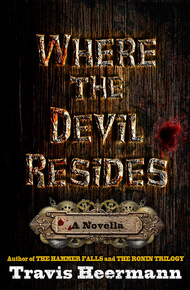

Amid the ashes of the Civil War, a Yankee minister boards an airship, little knowing that his world, maybe even his soul, will be destroyed.

When Willem and his family arrive in Key West, even the Union troops can't protect them from a gang of vicious, Confederate swamp rats, led by man called "Smilin'" Jack Welch, who's decided Willem's teenage daughter should belong to him.

Deep in the Everglades, a sorceress has foreseen the coming of a righteous man who'll help her scourge Welch's gang from her domain. But she needs Willem's blood to fuel her power.

Can she and Willem find join forces in time to save his daughter from an unspeakable fate?

"The story kind of has a bit of a Lovecraft vibe with a dash of a Philip Jose Farmer or Edgar Rice Burroughs or even a bit of a perverse Treasure Island. I enjoyed it. Kind of Wild Wild South or Wild Wild Swamp if you will."

– Amazon ReviewMy name is Willem van Dijk, and this is my account of the woman known as the Black Rose, what I saw in the depths of the Everglades, what we did, she and I. Gentle reader, my tale might stretch the bounds of your imagination, but I have gone beyond the need for human acceptance of what I know to be true.

Until recently, I was a pastor in the Dutch Reformed faith, and my ministry took me, along with my wife and daughter, from our home in Boston across Confederate soil to Key West. Undeterred even by tales of alligators, rum-runners, or bandits, my wife's pious fervor would not allow me to leave her behind where she would have been safe.

Nevertheless, how could we have, in good conscience, brought our daughter Emily with us to this God-forsaken place? Thoughts of wild adventures stoked a different kind of fervor in her. More adventurous by half than any woman should be, Emily was—

No, I must begin at the beginning, dear reader, so that you might grasp the enormity of what I have encountered.

It began when I received a letter from my cousin, Alfred Pennyton, a fellow man of the cloth, informing me that "an illness" had robbed him of his ability to maintain his congregation in Key West, and expressing his wish that I join him there and rebuild what he had lost. Moreover, "the comfort of family close by would be a great blessing." The letter included three airship tickets to Key West on the Etherglide, famous for its speed and luxury. How a minister could afford three such tickets I could not imagine. Alfred was considerably older than me, a bachelor, and one of the godliest men I had ever had the good fortune to meet.

My own frail constitution had become overtaxed by one too many difficult New England winters, and his letter described a veritable tropical paradise. I had never been a believer in wanderlust, but something about his offer struck me at the deepest core of my soul, and I could not refuse. My congregation was much discomfited at our departure, but their staunch, upright New England mien would hold them in good stead until a replacement could be found. We were never a family with ostentatious leanings, so packing our meager belongings into a couple of steamer trunks and suitcases was a relatively uncomplicated task.

Etherglide was a small ship, only a dozen seats, but the cabin was beautifully appointed and cozy, all polished wood and brass. The other travelers were well-heeled businessmen, and one of them even a Confederate plantation owner in a brilliant white suit and carefully teased mustache. The farther south we traveled, over Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, the warmer the air became, until the steward opened the portholes and admitted freshets of pleasant breeze and the lush, rich scent of forest and swamp. The patchwork of tobacco and cotton fields—and the numerous scars of war they still suffered—fascinated me such that I could hardly pry my eyes away from the portholes.

The immense intricacy of this modern contraption fascinated me, and the thrill of an eagle's eye perspective on the land below kept me fixed on the porthole almost as surely as was Emily. I reflected on the path my life might have taken if such wondrous contrivances had existed when I was a lad, and on the way a bit of human cleverness can affect something as vast and chaotic as a war.

The discovery of etherene had allowed the South to gain the advantage and turn the tide at Gettysburg. The Union generals were not expecting the arrival of airships that rained fire and destruction down upon them, setting entire regiments to rout. For almost a year, the Union was driven back onto its heels until it captured one of the new Confederate war machines and engineered their own etherene airships and the weaponry to accompany them, bringing the balance of power back to a stalemate. Because of this stalemate, the war raged on for more years than it might otherwise have done. And the prolonged war brought even more destructive weaponry, firearms that brought Hell itself to earth. These weapons were first shipped surreptitiously from England, soon copied by Union arms makers. The blood-soaked stalemate raged too long, and casualties piled to Heaven, until many of us had long forgotten why the war began in the first place. The war brought with it not only brutally efficient developments in firearms, but other machines as well, the like of which, as I am not scientifically minded man, I can scarcely fathom. The harnessing of lightning, of light, of perhaps the power over life itself, were subjects routinely discussed in newspapers and magazines. And this New Age of Science and Technology was inexorably chewing away at the frontiers of benighted savagery.

The heights terrified my wife, Mary—she spent most of the trip white- knuckled and clutching the arms of her over-stuffed seat—but, with a sensitive stomach, the prospect of an arduous sea voyage down the coast had been even more repugnant to her.

Emily, on the other hand, practically vibrated with excitement. Her eyes glowed with enthusiasm, and the sights of the land and coastline sliding past beneath us made her alternately giggle and weep with rapture.

Our conveyance paused at various ports along the way—New York, Washington, Charleston, Pickettville—to take on fuel, passengers coming and going. The churning of the miniature steam engine that drove the propellers was a constant companion. The sight of the cottony trail of steam and smoke we left behind filled me with an unfamiliar sense of adventure. I felt the majesty of God in the genius of man, in the verdant greenery draped over mountains and plains below us.

The land became a sparkling green and blue carpet of grassy marsh. The steward confirmed for me that we were over the Everglades, and I paused in awe at this vast expanse of alligator-infested wasteland.

As I had never set foot outside of New England, this was my first sojourn to any foreign land. With the Confederacy's coffers depleted, even five years after the Armistice, the nascent nation was hungry for currency, even Union dollars, especially in its poverty-stricken rural areas. President Lincoln's conciliatory visit to the Confederate States the previous year had gone a long way toward easing the tensions of almost a decade of war.

In his letter, Cousin Alfred assured me that Floridians were hungry for the Word of God and that the prospect of assembling a congregation for myself would be child's play. They would flock to my pulpit like moths to a lantern. And from there, I could further the Abolition movement. The winds of history blew with the currents of slavery's worldwide abolition, but the stalemate and cessation of the Great War had allowed slavery to perpetuate on American soil, at least for the time being.

Our arrival in Key West, this lonely bastion of Union presence, went largely unnoticed by anyone except our family. I was surprised to find myself both comforted and alarmed at the ubiquitous presence of so many blue coats. At the earliest moments of the hostilities in 1861, the commander of Fort Zachary Taylor had wisely jumped to the fore and secured the area around Key West, and for over a decade the presence of a powerful naval base had maintained a foothold against any rebel incursions. Florida itself had been largely spared any significant engagements. Tennessee, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, the Virginias and Carolinas, Maryland, Delaware, New Jersey, all of those were still rebuilding from devastating artillery barrages and firebombing.

The moment we stepped foot outside the airship's cabin, the hot humid air dredged a frightful torrent of perspiration out of me. My ministerial raiments soon proved as pleasant as wearing a heavy canvas sack, and Mary's high-necked frock was as quickly sodden.

Alfred had advised me to make sure that our travel papers were in order before we arrived, and they were immediately reviewed by a fat, deskbound sergeant at the foot of the mooring tower. The man warned us gruffly that Union protection stopped at the bridge.

I could barely restrain Emily from trying to make friends with everyone she met, but the lascivious glances of the soldiers were enough to set my fatherly defenses at high alert. In addition to that, the sight of so many guns worn in open view stretched my nerves thin.

I told the women again, "For now, speak only when spoken to. Draw no attention to yourselves. Who knows what sort of riff-raff we might attract?"

The island's fortifications suggested hostilities were still in action. Massive artillery batteries, great stone walls. A single red, white, and blue flag, surrounded by Colt machine guns on one end of the bridge, faced a different flag on the other, flanked by Enfield machine guns. Fort Zachary Taylor occupied only a portion of the island, but the entire town felt like a military installation.