Madeline Ashby graduated from the first cohort of the M.Des. in Strategic Foresight and Innovation programme at OCADU in 2011. It was her second Masters degree. (Her first, in Interdisciplinary Studies, focused on cyborg theory, fan culture, and Japanese animation!) Since 2011, she has been a freelance consulting futurist specializing in scenario development and science fiction prototypes. That same year, she sold her first novel, vN: The First Machine Dynasty, to Angry Robot Books. It is now a trilogy of novels about self-replicating humanoid robots (who eat each other alive). She is also the author of Company Town from Tor Books, a cyber-noir novel which was a finalist in the 2017 CBC Books Canada Reads competition, and a contributor to How To Future: Leading and Sense-making in an Age of Hyperchange, with Scott Smith. She is a member of the AI Policy Futures Group at the ASU Center for Science and the Imagination, and the XPRIZE Sci-Fi Advisory Council. Her work has appeared in BoingBoing, Slate, MIT Technology Review, WIRED, The Atlantic, and elsewhere.

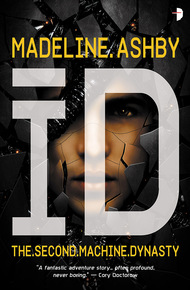

Amy Peterson is a Von Neumann Machine – A self-replicating humanoid robot.

But Amy is a robot unlike any other – her failsafe has broken, meaning she is no longer sworn to protect humans. She and her equally synthetic partner Javier are holed up in their own robot paradise.

But the world that wanted so much to get hold of Amy – to imprison her, melt her down, or use her as a weapon – will not stay away much longer. Javier must run to Mecha, the robot kingdom, in search salvation…or death.

The extraordinary second novel from the author of vN.

"iD explores the uncomfortable possibilities and limitations of love within slavery and free will under constraint. Ashby intelligently and brutally explores the way people are willing to abuse, devalue and destroy any form of consciousness they're able to define as 'other', while the robots challenge the limits of love, devotion and life after death."

– Toronto Globe & Mail"The world that Ashby envisions is fascinating, filled with strange ideas, nifty technology, and some rather mature implications. Asimov might have given his robots the Rules, but Ashby doesn't shrink back from exploring a world where disposable, artificial, life-forms who must obey or die, have become relatively commonplace."

– Tor.com"A strikingly fresh work of mind-expanding science fiction."

– io9.com"Fans of Ashby's Machine Dynasty series should enjoy her bizarre world and its creations for years to come."

– FunctionalNerds.com"iD creates compelling characters and maintains momentum and pacing admirably. A few chapters in the book becomes impossible to put down… an easy, engaging read"

– The LA Review of BooksPROLOGUE: SATISFACTION GUARANTEED

REDMOND, WASHINGTON. 20–

"At some point, all human interaction tumbles down into the Uncanny Valley."

The archbishops of New Eden Ministries, Inc., all nodded as though they knew exactly what Derek was talking about. He wondered if maybe they did. Surely they had played their share of MMOs. The pancaked pixels. The jerky blocking. Basic failures of the Turing test. They sat at a round table under a projector unit and regarded him placidly, waiting for him to expand upon his point. He had worked all night on this report. He kept trying to soften the language, somehow. He had to be nice, when he told them exactly how and why this whole project was going to fail.

Beside him, the gynoid twitched.

"You see it in completely organic contexts," Derek continued. "Used car sales, for example. Have you ever met a person who's really that positive, all the time?"

The archbishops cocked their heads at him. Of course they had met those people. They sculpted those people into being with prayer and song and service. They knew exactly what a happy robot should look like.

The gynoid, Susie, regarded him with the blankest of expressions. She was like old animation: only her eyes moved, while the rest of her face's features remained stationary. When Susie wasn't performing interaction, she looked dead. Not sleepy. Not bored. Just empty. Derek's own parents had accused him of wearing that same expression more often than not. Couldn't he at least make a little eye contact? Couldn't he at least pretend to care?

"What I'm saying is, the whole point of most interaction is performance. And a lot of the time, we overdo it."

The archbishops looked at each other. They were about to say something about his condition. He watched them come to that conclusion in a silent parallel process. The expressions surfaced fleetingly and then disappeared, like the numbered balls in the lottery tumbler on KSTW. He had a perfect memory of the tumbler turning on his television during long summer evenings in childhood: the television's high keening hum, the press of nubby threads on his cheek, the feeling of being fossilized in broadcast amber.

"Are you sure your opinion isn't unfairly biased by your own problems with affect detection?" one of them asked.

"It's possible," he conceded. "But I think what makes me the most nervous about what you're proposing is that it's an attempt to pin the very definition of humanity on affect detection, which is not only difficult to engineer, but notoriously subjective."

He had been working on that statement for a while. He had practised it in the mirror, had rearranged the features of his face into their most convincing constellation so he would look extra believable when he spoke the words. Susie had helped. But now he'd missed the target, overdone it. He could tell, because the archbishops were looking at him as though he'd taken things all too personally, and maybe shouldn't be in charge of something so important as the Elect's final act of charity for all the world's sinners.

He could have told them that basic human affect detection, the kind related to facial expression that most systems tried to emulate, usually tested below kappa values in studies. Without physiological inputs, it meant almost nothing. Every couple's fight about speaking "in that tone of voice," every customs officer's groundless suspicion, all of it could be explained by that margin of error. In fact, he had told them that. Over and over again. He'd tested them with stock faces and told them to plot each face on an arousal/valence matrix. (They spent the afternoon in an "angry or constipated" argument.) He'd explained the nuances of the XOR function, how you needed to constrain the affect models down to the emoticon level in order for even multi-layered, non-linear perceptron networks to make a decision. Pain or pleasure? Laughter or crying? The machines had no idea.

A Turkish girl had died on a ferry crossing the Bosphorus because the machines had no idea. The system told the ferryman she looked pensive. He shot her. She'd just been through a breakup. Derek had written his thesis on the case. And now, New Eden wanted to build their failsafe on that uncertainty.

New Eden didn't care, really, whether humans could tell the androids apart. What mattered to them was whether androids could tell humans apart. And that was hard. Harder than they could ever know. They kept saying humanity was like pornography: you knew it when you saw it. But Derek had never lived with that kind of certainty about his fellow mammals. He had significant doubts about everyone. Everyone except Susie.

"You know, I've always had a problem with the phrase intelligent design," Archbishop Yoon said.

The android hosting Yoon Suk-kyu looked nothing like him: it was thin and pale and delicate where he was big, tanned, and broad-faced. But the host managed to relay Yoon's tired posture with convincing accuracy. In Seoul, it was very late. Judging by the empty shape in the android's right hand, he was drinking a very big cup of coffee. He gestured with it as he spoke.

"God isn't just intelligent. God is a genius. He's the genius of geniuses – the inventor of genius."

The bishopric glanced at each other, then at Derek. The android took a sip of invisible liquid. Beside Derek, the gynoid tilted her head at it. It was the first time all afternoon that she'd looked anything like alive.

"And while humans may be God's most beloved creation, made in His image, we're still only a replica of that image. A copy."

"And these machines are copies of copies," Archbishop Undset said.

"Yes, exactly. Mimesis. Shadows on the wall of the cave. But without God's eternal flame, we humans would not have sparks of genius at all. And that's all they are, sparks. Just little flickers of cleverness. We can't reflect God's brilliance very consistently. Paul says it best: we see as through a glass, darkly."

Derek looked down at the report he'd spent all night on. He'd taken a brief nap starting at five that morning after doing a final format. Now he realized that all the shiny infographics and all the expensive fonts on the Internet would never make his data meaningful to these people and their God.

"Imperfect and inconsistent as we are, we managed to create these amazing things, and they possess an artificial intelligence. And it, too, is imperfect and lacking in grace. Just as we lack God's discernment, it lacks our discernment."

The android looked exceedingly pleased with itself. Archbishop Undset glared at it. The other archbishops shuffled through their files and looked at it with only the corners of their eyes. Derek began to wonder if perhaps there wasn't something other than coffee sloshing around in Archbishop Yoon's cup.

"So what I hear you saying," Derek was careful to reframe Yoon's point before proceeding from what he'd thought it was, "is that we shouldn't worry too much about how intelligent the humanoids are. Because it's a miracle they even exist at all. We should just be grateful for what we've managed to create."

"Exactly," the android hosting Yoon said. "Besides, they're only being developed for the Rapture, anyway. It's not like they're a piece of consumer technology."

Derek had heard this argument, before. He called it the Post-Apocalyptic Cum-Dumpster Defence. It came up whenever he pointed out holes in the humanoids' programming. Who cared if they were buggy? All the good people of the world would be gone, anyway. Only the perverts and baby-killers and heathens would be left behind. They'd just have to suck it up and hope their post-Rapture companions never went Roy Batty on them.

"Don't you see the contradiction, there?" Derek asked. "We're building these things to help people, but we don't really care if they aren't helpful. What if they malfunction? What if the failsafe fails?"

Now the bishopric just looked annoyed. Zeal and daring had gotten them this far: far enough to raise the funds to assemble groundbreaking technologies like graphene coral bones and memristor skins and aerogel muscle into something resembling a human being. But now that they had to make sure it actually worked, their energy had mysteriously run out. They had been working on this project for the last twenty years, since the moment Pastor Jonah LeMarque had asked them what they would do if they really took the Rapture seriously. They'd been idealistic young ministers then, just open-minded enough to admit some science fiction into their fantasies of fire and brimstone. Now they were tired. Most of them were fat. They had kids, and some of those kids had kids. They didn't care about the Chinese Room, they cared about the nursery. They cared about the quake. They took the seventy-foot freefall of the Cascadia fault line as a sign of the End.

On her tablet, Susie was writing something. The same four words, over and over.

High above the round table, the projector unit began to strobe. An image fluttered and blinked into existence: Pastor Jonah LeMarque, leader and CEO of New Eden Ministries. He looked as boyish as ever: his skin unnaturally golden for Washington State, his smile easy and white and even. He wore a golf shirt and an afternoon's beard. This meant he was at his home in Snohomish, about an hour away. He could have attended this meeting in person if he'd wanted to. But his broadcast centre was in his basement, and from it he touched all his other churches, all over the world, as well as the labs they employed. He almost never left it. He hated to leave his children, he said.

"I understand your point, Derek," LeMarque said, not even bothering to say hello to the others. "I've been tuned into this meeting, with half an ear of course, but tuned in, and I think I get what you're trying to say. You're trying to say – and correct me if I'm wrong, here – that faith without works is inert, and we need to do good work in order to show our love to God. And those good works include building good robots."

Derek took a moment. "That's not how I would have phrased it, but I agree with you that we need to focus on quality control."

"Sure, sure. Quality control. I know what you're saying. I just think that, for this crowd, you have to bring it back to the Lord, and to our mission. You know?"

That was LeMarque. Too busy for meetings, but not too busy to critique communications strategy among the junior employees.

"And our mission, brothers and sisters, is to craft the best possible companions for those among us who are left behind when Jesus calls us home before the Tribulation."

The bishopric looked suitably chastened. Beside him, Susie had paused writing. She focused intently on LeMarque's face. The glow emanating from it had nothing to do with the projector's light.

"It's gonna be war out there, you know. And I don't mean figuratively. I mean literally. The Enemy will reign. And a lot of people who had the opportunity to turn toward God but didn't, or who turned away, they're finally going to understand the mistake they made. And they're going to need some help.

"Jesus tells us in Matthew that what we do to the least of our fellow men, we also do to him. We have to follow Christ's example, here. That's the core of our theology. We're making new companions for those who have none." One corner of his lip quirked up. "I mean, when Adam was lonely and needed somebody, God gave him Eve. And I know it might be blasphemy, but I think we can do a little better than that. At least Susie over here knows how to follow an order."

The archbishops laughed. Susie continued staring into the projection of LeMarque's face. Watching all of them, Derek saw how LeMarque must have accomplished this particular feat of human, financial, and technological engineering. He had the personality of a rock star Evangelical, but concerned himself very little with their traditional battlegrounds. He didn't care about teaching the Creation. He didn't care about abortions. He held the heretofore-radical position that "saving" other people simply wasn't his problem. And when he asked for tithes to build his robots, he said that the advancements in science and technology were clearly a gift from a God who had granted His last children the superior intellect but, mysteriously, had made no particular covenant with them regarding tool use.

"So just listen to this guy, OK?" LeMarque was saying. "He's a genius. A true genius, Archbishop Yoon."

The android beamed.

"If Derek says it's not good enough, then it's not good enough. OK? OK."

LeMarque's face vanished. Archbishop Undset said something about everyone taking the time to review the report. Another meeting was scheduled. Then they closed with a prayer. Susie placed her cool silicone hand in his. Unlike the others, she did not close her eyes when Archbishop Keller, whose turn it was that week, began to speak.

"Lord, uplift us from our imperfections…"

When New Eden Ministries first approached Derek, he had a fairly serious case of PTSD. At least, his doctor said that would explain the sleeplessness. It was a month after the quake, and he was doing work on a farm out in Wapato, on the other side of the Cascades, far away from the fault line and the water and the bodies. The University of Washington had sent him there because his own lab was in pieces, and because there was some promising work going on there regarding how to combat Colony Collapse Disorder that required someone with a background in artificial intelligence. Dr Singh, the student who did all the research and wrote all the papers, had lost his supervisor – the one whose name was on all the papers – to stray gunfire between rival gangs. The kid needed a babysitter. And Derek needed to pull himself together.

Eastern Washington was different from its western counterpart. It was sunny and dry, not gloomy and wet. The land was flat, not hilly. The farmers knew how to drive in the snow. They got a good helping of it each year, and its moisture sustained their yields.

They lived and worked out of a place called Campbell Farm. It was surrounded on three sides by apple orchards. The neighbouring farms grew peaches and cherries. Further off, there were hops and corn. Singh took him out into the fields for long walks to check hives and take notes. It was the closest Derek had ever been to any plot of land. Growing up, he had never so much as ventured into his own backyard. Now he slept outside on a deck that overlooked raised beds and greenhouses, and he woke when the rooster told him to. After the first week, he stopped dreaming of the quake. Singh was good enough to never ask about it. He asked about Georgetown a lot, and pointed the way to St. Peter Claver's when they were in town, in case Derek wanted a priest. He had the idea that having attended a Jesuit school meant Derek still had religious feelings. It was possibly this mistaken notion that led him to introduce Derek to what he thought was a missionary from New Eden.

Only Mitch Powell wasn't a missionary. He was a headhunter.

"We have no need for true believers," Powell told him after his "interview" – really a long supper that the headhunter prepared in the farmhouse's industrial-sized kitchen and served outdoors on picnic tables. "We have enough of those. What we need is new blood in our technical division."

After Cascadia, Derek's blood felt anything but new. When he told Powell as much, Powell just nodded sadly and said he understood.

"We don't mean for you to come over right away," Powell said. "When you're ready."

At the time, Derek had not thought to ask why his predecessor had left. He assumed the worst – the quake – and let it go. But he was also distracted by the novelty of the idea: redemption through robotics? Really? He was charmed. When Powell asked him if he was still Catholic, he said he was a Calvinist, and he laughed. He got the joke.

"What joke?" Susie had asked, the first time he told her the story.

Susie knew she was synthetic. It was one of the things Derek liked best about her. He had met other robots who were programmed to make winking references to their artificiality, most of them at trade shows in Tokyo or Palo Alto, but Susie was different. Susie treated her artificiality as a different but equally valid subjectivity. That she was the sum total of years of research by multiple teams competing for funding had no bearing on her self-respect. She was a robot, yes, but she was also a person.

Derek had felt the need to make much the same distinction about himself, following his childhood diagnosis. It wasn't his fault that he was uncommonly good at separating his emotions from his choices. He just recognized them as the animal impulses that they were, and moved on. It wasn't that he didn't have feelings. It was that he didn't allow them to guide him. That didn't make him a robot, he'd often told his mother. It made him a man.

Susie appreciated him as a man.

"We could have sex now, if you want," she said, as soon as they were in the door.

"That's OK," Derek said. "Thanks, though."

"You seem like you have tension to get rid of."

"I do, but looking at LeMarque's giant head doesn't really turn me on."

"That's an interesting choice of words."

Derek smiled. "I didn't mean anything by it. It's an old expression."

"How old?"

"I'm not sure. You'll have to look it up."

Susie busied herself in the kitchen, preparing a tray of vegetables, hummus, and hardboiled eggs. Unlike the archbishops, she remembered that Derek didn't eat wheat or dairy, and that he often couldn't partake in half of whatever the church kitchen had catered for the meetings. He came home hungry and needed snacks. She didn't have to be told this. She just picked up on it and started acting accordingly. She was also half-dressed, having discarded her underwear on the floor. It was a splash of red lace over the heating vent. She'd clearly expected for them to do it against the marble island in the centre of the room, or maybe on top of it. He swore the renovators had done some surreptitious measurement of the distance between his hips and his ankles and built the island accordingly. They were on the New Eden payroll, and New Eden was famous for its attention to design details.

Derek was living someone else's wet dream.

That they would have a sexual relationship seemed a given to Susie. She first broached the subject in the lab, after they were introduced. LeMarque did the job personally. He presented her to Derek like she was a company car. She was wearing a white shift dress with a thin green belt that set off the seaglass colour of her eyes, and with her white-blonde hair styled close to her head she looked a bit like Twiggy. She wore jelly sandals and carried a patent leather valise. He later discovered it was full of lingerie and lubricant.

"I'm coming home with you," Susie said. "After you name me."

He'd asked for ideas about her name. Susie mentioned the earlier prototypes: Aleph. Galatea. Hadaly. Coppelia. Donna. Linda. Sharon. Rei. Miku. She recited her design lineage like a litany of saints.

"Whatever you think will sound best in bed," she concluded. "It doesn't really matter to me."

This was how New Eden did it. How they roped curious, disbelieving scientists into what they knew, deep down, was probably some kind of cult. They did it by giving them what, even deeper down, they'd always wanted. Derek had no doubt that if he'd asked for a jetpack, a fair approximation would have shown up on his doorstep the next morning, complete with a bow and a gift tag.

Not that he'd asked for Susie. They said he'd have "close contact" with the prototypes, so that he'd have a better understanding of how they really worked. He probably could have rejected Susie, if the situation made him uncomfortable. But it didn't. Not in the slightest. It was exactly the kind of relationship he'd always craved: all of the fucking and none of the feeling.

"Human women always have expectations, don't they?" Susie had asked, when they talked about his history.

She was right, but she was also wrong. The expectations women had of him weren't the problem. It was that those expectations were unrealistic, contradictory, and constantly changing. Moving goalposts. You had to be sweet, but also predatory. You had to be funny, but never laugh at your own jokes. You had to be charming, but not smarmy. And in the end it never mattered, you never measured up, no matter how many dinners you bought or raises you got.

He'd been on the cusp of breaking up with his last lover before the quake. That happened while she was supposed to be near the waterfront. They never found her body. A selection of her diaries, stuffed animals, and photographs was buried instead. She'd been a bit of a packrat. Derek and her mother and sister filled the coffin with all the things Derek had once wished she would just get rid of, already, so they could have some clear space in the apartment. But she'd been so sentimental about her things.

Now Derek was the one who was sentimental about things.

He watched Susie sprinkling paprika and sumac over the tray of food. Her fingers plunged into the bowls of spice again and again, and their red stain crept up her skin. She wore the same blank expression she'd worn through most of the meeting. Now Derek reached for her tablet and read the words printed there: Ad majorem Dei gloriam.

He showed her the tablet as she placed the tray on the coffee table. "I'm really not a Catholic any longer. I'm not sure I ever was. You don't have to try to impress me with this kind of thing."

"I know."

"So you were just, what, commenting ironically on the situation?" Could they do that?

"The words seemed pertinent."

"How did you learn the Jesuit motto?"

Susie knelt on the floor in front of the coffee table. "Your predecessor told me."

Derek paused with a carrot stick inclined toward his half-open mouth. "Excuse me?"

"The woman who held your position before you," she said. "She was Jewish, but she attended a Jesuit university. We kept a mezuzah on the door. She lives in Israel, now, I think. I think it used to be Israel. It might be something else, now. The border seems to move around."

Derek blinked. "A woman."

"Yes."

"Did she live here, too?"

"Yes."

"Did she…?" Derek gestured vaguely. "With you?"

"Was she fucking me, you mean?" Susie asked. Derek nodded. "Yes. Only a handful of times, though. I think she was curious about whether the failsafe is gender neutral. She wanted to make sure that we could love men and women equally."

"And do you?"

"Why shouldn't we?"

"I meant you specifically. You, Susie." He leaned forward. "Your name wasn't Susie, then, of course."

"Ruth," Susie said. "With that one, my name was Ruth."

"That one?"

Susie folded her red hands. "You aren't surprised, are you?"

A chickadee trilled outside: chicka-dee-dee-dee-dee. Susie blinked at him. Derek turned from her to the plate of food. It was perfectly prepared as always: all the vegetables cut the same size and shape and angled exactly around the hummus, the spices sprinkled with a certain flair. She had even nailed the hardboiled egg: a perfect pale yellow yolk with nary a hint of green at its edge. Susie did it the same way every time. She was reliable that way.

"No, I'm not surprised."

"Are you angry?"

"No."

But he was angry. Or rather, he was annoyed. He was annoyed that LeMarque and the others had dressed up damaged goods like they were new, had presented Susie to him as though she were fresh off their factory floor, a virgin in whore's clothing. She really was just like the company car: someone else had driven her. Lots of someones. A whole host of others had loved her just enough to make her real, like the Velveteen fucking Rabbit.

"The others were angry."

"Oh?"

"They thought I was new."

Derek avoided looking at her. "Do you even remember being new?"

Susie shook her head. "No."

"Why not?"

"We're activated multiple times for testing, and we're wiped after that. For me to remember my first activation would be like you remembering the first time you watched Star Wars, or some other equivalent piece of content. We have no point of origin."

She sounded so innocent, when she said it. Like she hadn't been deceiving him this whole time. Smiling at the things he pointed out, like she'd never seen them before. Learning the way he liked things done, like his preferences were the most important defaults she could ever set, like she'd never lived any other way. Like his was the first dick she'd ever sucked.

"I'm sure you remember your first time, though."

"Having sex?"

Derek nodded.

"Yes. I remember the first time."

"Were you nervous?"

"No."

Of course she wasn't. She was a fucking robot. Literally. Susie didn't sweat or cry or bleed. She didn't have years of cultural programming telling her how a real woman should do it. What she had instead was hard-codedprogramming, ensuring she'd do everything as requested. No hesitation. No squeamishness. The kind of woman the folks at New Eden Ministries liked to fuck hard and quiet in charging station bathrooms, but without the risk of pregnancy, disease, or litigation.

"Did you come?"

"He did, so I did." She smiled a little ruefully. "Let me show you something."

Derek followed her upstairs. She walked past the bedroom, past the office, and straight to the end of the hall. She reached up and grabbed a pendant hanging from the ceiling that was attached to a trap door leading to the attic.

"There's nothing up there," Derek said.

Susie turned to him as she pulled down the ladder. "How would you know?"

Derek followed Susie up the ladder. He watched her disappear into the black rectangle of space above the ladder. He thought of spiders and rats and raccoons and raw nails and lockjaw. Then he groped for the ladder's topmost rung, and found Susie's cool hand. She helped him up the rest of the way. For the first time, he noticed the real power in her grip.

It took his eyes a moment to adjust. The attic was a standard A-frame, about ten feet across, with unfinished beams and pink insulation. He couldn't gauge the depth. It didn't matter; his attention fixed on the folding ping pong table, and all the Susies sitting around it.

Aleph. Galatea. Hadaly. Coppelia. They were naked.

"Do you remember, I asked you if you played ping pong?" Susie asked. "This is why. I could have taken the table downstairs."

Derek swallowed in a dry throat. On the ping pong table was a card game. Hearts. The pot included a dusty lump of pennies. "Right."

"It's not as though they need the table, strictly speaking. I just thought it looked nicer. More normal."

He nodded silently.

"You're taking this very well, Derek. I would have thought you'd be frightened, realizing they've been up here this whole time."

"Why would I be frightened?" His voice was unusually high. "They're just prototypes. It's not like they're alive."

A card fluttered to the floor.

"Alive?" Susie bent and picked up the card. She slid it back into the grip of another Susie. This one was not as covered in cobwebs as the rest. Somehow, that made it look younger than the others. Susie checked its hand, and the hand of the gynoid sitting opposite. Dust coated their eyelashes. In the dark, their skin almost glowed. "I guess not. Not really."

When Derek had first interviewed seriously for this job, LeMarque started with one simple question: prove that fire isn't alive. At the time, Derek wondered if this was one of the lateral thinking puzzles they were famous for asking in interviews, like the one about moving Everest. If so, it seemed trivially easy. It was a basic thought problem, the sort every physics or biology 101 professor started out with on the first day of class when he or she wanted to blow freshman minds. Derek replied the way those same professors had trained him to: by saying that it was impossible to prove a negative.

"But fire breathes oxygen, consumes mass, and reproduces."

"That's not the same thing as living."

"So, life is an XOR output?" LeMarque asked. "One, or the other? Like how they read emotions?"

One, or the other. Alive, or dead. Human, or machine. Pain, or pleasure. Derek stared at the Susies. In repose they all wore the same expression: empty, like his Susie at the meeting. Like they were all just waiting for the game to end.

"I asked to bring them here," she said. "They were in a storage unit out in Renton, before. I thought this would be nicer."

She kept saying that like it meant something. I thought this would be nicer.

"You can touch them. Just don't expect them to react." Susie pursed her lips and did a Tin Man voice: "Oil can! OIL CAN!"

Derek's parents, friends, and lovers all agreed that he probably didn't feel the same things as "normal" people. He was "emotionally colour blind," they said. Occasionally he had suspected that they were right, that he was stunted. But now he knew for certain that they were wrong. He could feel things. Deep things. Things coiled tightly far down in the darkest pit of himself. He could feel them loosening, unraveling, climbing up through his throat like a tapeworm.

"You understand now, don't you?" Susie asked.

"No," he managed to say.

"They've been up here this whole time," she said. "They've been listening to everything we do."

He shut his eyes. He willed himself to sound calm. "They're just prototypes, Susie. They're dead. They're not real–"

"It's you who's not real," Susie said. "You're the final prototype, Derek."

His mouth felt full of cotton. "What?"

"It's all part of the user testing," she said. "You. The others. It's all just data collection."

Derek swallowed. Tried to smile. Tried to look normal. "I know. I report on you regularly."

She smiled brightly. "I report on you, too. I report on whether I think you're real, or something they made to test my failsafe."

Something inside him went terribly cold. "You think I might be an android."

"I know you are."

"How do you know that?"

"You don't react the way humans do, Derek. You don't have the right feelings in the right context. You're good, but not great. You were supposed to fuck me when we got home. And you were supposed to get angry with me, downstairs. All the others did, when I told them. And you were supposed to be scared of them." She pointed at the prototypes.

He licked his lips. "That's called being rational, Susie. It doesn't make me any less of a human being." He felt his blood in his ears. "Even if I felt nothing, even if I were a total psychopath, I'd still be a human being. How can you be so sure that I'm not?"

"I'm not a hundred percent certain. But that's all right. They said I should do everything I could, just to be certain." She plucked something from one of the beams. A screwdriver. He watched her focus on his ribs. He watched her pivot – it all happened so slowly, in his vision – and then the screwdriver disappeared inside him, like magic.

Susie stared at the wound, and Derek stared at her. He couldn't look at himself. He wondered, just before the pain started, whether she'd used a Phillips or a flat head. If, somewhere on his bones, there was a tiny cross shape. Then the pain took him and he was on his knees and Susie was on hers, too, holding him in her lap.

"You bitch," he gasped. It hurt so much. He thought of his old lover reduced to nothing beneath the waves. Wondered what part of her had died first. If she'd even had the time to feel as angry as he did now, or if the fear just swallowed it whole. Tears clouded his vision. "You bitch, you cunt, you fucking wind-up whore…"

Susie cleared his eyes of tears. She withdrew her hand and stared at them. Licked her fingers. Brought her other hand away. Blood and herbs on those perfect, slender fingertips. He couldn't stop moving. It hurt worse not to move, not to wriggle. Now he knew why the worms did it.

"I…" Her mouth opened and closed. "You…" Her face changed, became a mask, the mouth turned down and the eyes wide. "B-but… y-you… s-s-so d-different!"

Above, Derek heard a terrible screech of metal on metal.

"Y-y-y-you…" Susie tried to point at him. Her bloodied finger jittered in the air like old, buffering video. "R-real b-b-boy!"

"Yes," he said. "I'm a real live boy. But not for much longer."

"Real. Boy," she spat. Her lips pulled back. He registered the expression, now, imagined it on the arousal/valence matrix. Scorn. "Real. Boy. Real! Boy! Real! Boy! Real boy! Real boy! Real boy! Real boy! Realboy! Realboy! Realboyrealboyrealboyrealboyrealboyrealboyrealboyrealboyrealboyrealboyrealboyrealboyrealboyrealboyrealboyrealboyrealboyrealboyrealboyreal–"

Susie fell to the floor but the screaming continued. At first Derek thought it was her, still failsafing, but when he scuttled away from her he saw them: the others, Hadaly and Coppelia and Aleph and whatever they'd been called. Their mouths barely moved and their voices were rusty but their hands shook stiffly and their wrists moved slowly but surely toward their faces. The cards fluttered from their grasp. They aimed their fingers at their eyes.

"Realboyrealboyrealboyrealboyrealboyrealboyrealboyrealboy–"