Robert J. Sawyer is one of only eight writers ever to win all three of the world's top awards for best science-fiction novel of the year: the Hugo (which he won in 2003 for Hominids), the Nebula (which he won in 1996 for The Terminal Experiment), and the John W. Campbell Memorial Award (which he won in 2006 for Mindscan). He has also won the Robert A. Heinlein Award, the Edward E. Smith Memorial Award, and the Hal Clement Memorial Award; the top SF awards in China, Japan, France, and Spain; and a record-setting sixteen Canadian Science Fiction and Fantasy Awards ("Auroras").

Rob's novel FlashForward was the basis for the ABC TV series of the same name, and he was a scriptwriter for that program. He also scripted the two-part finale for the popular web series Star Trek Continues. His 24th novel, The Oppenheimer Alternative, was published in June 2020.

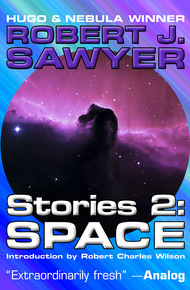

One of three volumes comprising the collected short fiction of Robert J. Sawyer, spanning his 40-year writing career. This volume, Space, collects his fiction set off the mother planet, and Hugo Award-finalist "The Hand You're Dealt" and Aurora Award-winners "Stream of Consciousness" and "Ineluctable," plus, for the first time in print, Rob's first sale, "Motive," which originally was produced as a dramatic planetarium starshow. Featuring an introduction by Hugo Award-winner Robert Charles Wilson and Rob Sawyer's notes on each story.

"Sawyer's collection showcases not only an irresistibly engaging narrative voice but also a gift for confronting thorny philosophical conundrums. At every opportunity, Sawyer forces his readers to think while holding their attention with ingenious premises and superlative craftsmanship."

– Booklist"Sawyer's latest collection is highly entertaining and thought-provoking; the book has something for almost any science-fiction fan. It is a testament to Sawyer's talent that it is not necessary to be a sci-fi fan to enjoy his writing; this is a collection of great stories that just happen to be set in the future."

– Quill & Quire"A fine addition to any short fiction collection focusing on science fiction."

– Midwest Review of BooksFrom "Above It All" by Robert J. Sawyer:

Rhymes with fear.

The words echoed in Colonel Paul Rackham's head as he floated in Discovery's airlock, the bulky Manned Maneuvering Unit clamped to his back. Air was being pumped out; cold vacuum was forming around him.

Rhymes with fear.

He should have said no, should have let McGovern or one of the others take the spacewalk instead. But Houston had suggested that Rackham do it, and to demur he'd have needed to state a reason.

Just a dead body, he told himself. Nothing to be afraid of.

There was a time when a military man couldn't have avoided seeing death—but Rackham had just been finishing high school during Desert Storm. Sure, as a test pilot, he'd watched colleagues die in crashes, but he'd never actually seen the bodies. And when his mother passed on, she'd had a closed casket. His choice, that, made without hesitation the moment the funeral director had asked him—his father, still in a nursing home, had been in no condition to make the arrangements.

Rackham was wearing liquid-cooling long johns beneath his spacesuit, tubes circulating water around him to remove excess body heat. He shuddered, and the tubes moved in unison, like a hundred serpents writhing.

He checked the barometer, saw that the lock's pressure had dropped below 0.2 psi—just a trace of atmosphere left. He closed his eyes for a moment, trying to calm himself, then reached out a gloved hand and turned the actuator that opened the outer circular hatch. "I'm leaving the airlock," he said. He was wearing the standard "Snoopy Ears" communications carrier, which covered most of his head beneath the space helmet. Two thin microphones protruded in front of his mouth.

"Copy that, Paul," said McGovern, up in the shuttle's cockpit. "Good luck."

Rackham pushed the left MMU armrest control forward. Puffs of nitrogen propelled him out into the cargo bay. The long space doors that normally formed the bay's roof were already open, and overhead he saw Earth in all its blue-and-white glory. He adjusted his pitch with his right hand control, then began rising up. As soon as he'd cleared the top of the cargo bay, the Russian space station Mir was visible, hanging a hundred meters away, a giant metal crucifix. Rackham brought his hand up to cross himself.

"I have Mir in sight," he said, fighting to keep his voice calm. "I'm going over."

Rackham remembered when the station had gone up, twenty years ago in 1986. He first saw its name in his hometown newspaper, the Omaha World Herald. Mir, the Russian word for peace—as if peace had had anything to do with its being built. Reagan had been hemorrhaging money into the Strategic Defense Initiative back then. If the Cold War turned hot, the high ground would be in orbit.

Even then, even in grade eight, Rackham had been dying to go into space. No price was too much. "Whatever it takes," he'd told Dave—his sometimes friend, sometimes rival—over lunch. "One of these days, I'll be floating right by that damned Mir. Give the Russians the finger." He'd pronounced Mir as if it rhymed with sir.

Dave had looked at him for a moment, as if he were crazy. Then, dismissing all of it except the way Paul had spoken, he smiled a patronizing smile and said, "It's meer, actually. Rhymes with fear."

Rhymes with fear.

Paul's gaze was still fixed on the giant cross, spikes of sunlight glinting off it. He shut his eyes and let the nitrogen exhaust push against the small of his back, propelling him into the darkness.

# # # # #