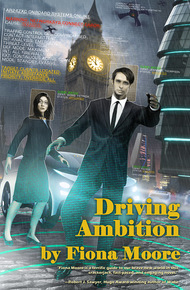

Fiona Moore's fiction and poetry has appeared in, among others, On Spec, Asimov, Interzone, and Unlikely Story, and no less than three Bundoran Press anthologies. She has written and cowritten numerous articles and four guidebooks on cult television, and has cowritten three stage plays and four audio plays. When not writing, she is Professor of Business Anthropology at Royal Holloway, University of London, where she is best known for a three-year-long study of a car factory. More details can be found at www.fiona-moore.com.

In the not-too-distant future, intelligent Things are recognized as sentient beings—but do they have the same rights as humans? And what about the free-floating Intelligents deep within the Internet? Thompson Jennings is a man with unique problems and unique abilities—he can interface between the human and machine worlds, acting as a go-between in labour negotiations and other disputes. But when one his clients—a sentient taxicab—is murdered, his problems multiply and his abilities are stretched to the limit.

"The Internet of Things! Self-driving cars! Artificial intelligence! Oh, and murder, too. Fiona Moore is a terrific guide to our brave new world in this crackerjack, fast-paced, and engaging novel."

– Robert J. Sawyer, Hugo Award-winning author of Wake"Driving Ambition provides one of the most sophisticated, sensible, and sensitive takes on the concept of artificial sentience that I have read, while still unfolding a gripping story, and offering a life-affirming ending. I found its take on technology delightfully refreshing - neither utopian, nor dystopian, but intelligent and compassionate. Truly a lovely book."

– Amazon Reviewer"In these days of issues-driven sci fi, it's a joy to read a novel that captures all the best traditions of science fiction: big ideas, enthusiasm for exploring the what-ifs arising from them and an intriguing plot all presented with a freshness that's thoroughly engaging and meaningful without descending into darkness."

– Goodreads Reviewer"Did you hear about the motorbike accident in Oxford High Street this weekend?" I asked Trish by way of distraction as we advanced grimly towards the mob of protesting cars in Soho Square.

"Oh, yes," she said, brightly, the escaped hair blowing around her face in dark Botticelli waves. "I understand the motorbike is expected to make a full recovery."

"Good to know," I said. The motorbike was a friend of a friend, and I'd always thought he ought to leave that stupid driver of his. After this, his driver would undoubtedly be prosecuted for Endangering the Continued Existence of an Artificially Intelligent Being, possibly barred from driving, and maybe Yetaxa would be able to choose a better owner.

The mob, meanwhile, were blaring their horns in rhythm, flashing their lights and attempting, as much as possible in narrow, crowded Soho Square, to drive around in fancy manoeuvres. Some had gone to the trouble of having slogans painted on their doors and windshields: RESPECT THING RIGHTS, said one. SAFE TAXIS UNFAIR TO SELF-DRIVING CARS said another. Well, most Things I knew tended to lack creativity with language, and self-driving cars especially so; this was probably about as original as they would get. Although Trish couldn't hear what they were saying to each other, I could; the world inside my head was a cacophony of shouted slogans and surprisingly creative suggestions about what management could do with its hiring and remuneration policies.

A pair of Texcoco mini-vans, blocky in bronze paint, span in together to block us with their fenders; then one of them recognised me (although I'm not sure how), flashed its lights, had a brief conversation with the other one, and they span out, telling the other cars who we were. With curt acknowledgements, several of them shifted to give us an access route. I made a note to find out who it was. Off the Internet of Things and in physical space, I found it hard to tell one car from the other, and I wasn't exactly in a position to ask right now. I was pretty certain the little racing-green Verve four-seater parked discreetly around the corner from the demo was Egon, at least.

"Verves and Texcoco," I remarked, scanning the cars in the square. The Verves mid-range and practical, hatchbacks and saloons, nipping and darting and flashing their lights; the Texcoco larger, mini-vans, vans and SUVs, taking up as much space as they could. But the small, sleek, space-age city cars were conspicuously absent. "No Ariels. You notice that?"

"I suppose, now that you mention it," Trish said, clutching her tablet-case protectively against her red wool coat. I reminded myself to cut her a little slack. It was Trish's first time on a Joint Negotiating Committee for the Union of Thing Transport Workers, and as far as I knew she hadn't had much to do with Things before taking the job as their new legal advisor. Might have taken a ride in a car, or hired a drone, or lived or worked in a building which had a concierge or a house-elf, but most people who use Things don't really attempt to get to know them. No wonder she was tense.

Somewhere nearby I heard a human desperately attempting to reason with one of the cars: "Look," a frustrated voice was saying in impeccable, annoyed, precise English: "I only want to hire a taxi…." The voice was drowned in a derisory chorus of angry horns.

Thanks to the Texcoco's intervention, we made it safely to the pavement in front of the London offices of Safe Taxis International, accompanied by a brief fanfare of horns, and it was there that we found the human protest.

"What the hell?" Trish's eyes widened under her sweat-streaked forehead and she took a harder grip on the tablet-case.

"Wasn't expecting them," I said, unable to come up with anything cleverer. The humans were rather better in their command of slogans: Down With These Sorts of Things, read one sign, and I made a mental note to congratulate the writer if ever I met them. They were also rather more destructive than the cars; a screwed-up cola bottle bounced off a windshield and the windshield's owner hooted derisively.

"Who are they?"

"Off-grid group," I said. The natural-fibre clothing, the plain-cut hair, the general air of people who insist on handcrafted everything. I was trying to figure out which group it was and praying to whatever deity looks after nonbelievers that none of my brother's friends were in it. Or worse, my brother himself, though I didn't think he left the farm too often these days. "Probably groups, plural."

"They still exist?"

"Oh yes," I said. Some of the protestors were dressed in dark colours and looked a bit better groomed, and some had the traditional guy-fawkes graffito painted on their signs. That wasn't a good sign; it suggested a collaboration, or infiltration, between off-gridders and anonymists. Off-gridders you could sometimes reason with; anonymists, not so much.