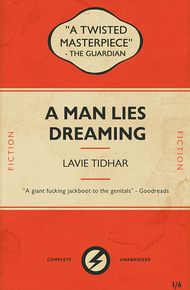

British Science Fiction, British Fantasy, and World Fantasy Award winning author Lavie Tidhar (A Man Lies Dreaming, The Escapement, Unholy Land, Circumference of the World) is an acclaimed author of literature, science fiction, fantasy, graphic novels, and middle grade fiction. Tidhar received the Campbell, Seiun, Geffen, and Neukom Literary awards for the novel Central Station, which has been translated into more than ten languages. He is a book columnist for the Washington Post, and is the editor of the Best of World Science Fiction anthology series. Tidhar has lived in Israel, Vanuatu, Laos, and South Africa. He currently resides with his family in London.

1939: Adolf Hitler, fallen from power, seeks refuge in a London engulfed in the throes of a very British Fascism. Now eking a miserable living as a down-at-heels private eye and calling himself Wolf, he has no choice but to take on the case of a glamorous Jewish heiress whose sister went missing.

It's a decision Wolf will very shortly regret.

For in another time and place a man lies dreaming: Shomer, once a Yiddish pulp writer, who dreams lurid tales of revenge in the hell that is Auschwitz.

Prescient, darkly funny and wholly original, the award-winning A Man Lies Dreaming is a modern fable for our time that comes "crashing through the door of literature like Sam Spade with a .38 in his hand" (Guardian).

A Man Lies Dreaming is probably my favourite novel of mine, and this is a brand-new edition, hot off the virtual press, and, I hope, just as funny, sad and disgusting as it's always been. I couldn't resist sharing it here. – Lavie Tidhar

"Complex, elusive and intriguing."

– The Jerusalem Post"Nasty, clever, waspish and witty… a brilliant and potent thought experiment."

– The Sunday Herald"Bold and unnerving."

– NPR"The best book I read last year is A Man Lies Dreaming by Lavie Tidhar... It is so cleverly constructed and such a spectacular conclusion unfolds that you are going to take it all very seriously."

– Sting"Ambitious as hell."

– Ian Rankin"An excellent novel."

– Philip Kerr1

Extract from Wolf's Diary, 1st November 1939

She had the face of an intelligent Jewess.

She came into my office and stood in the doorway though there was nothing hesitant about the way she stood. She gave you the impression she had never hesitated a moment in her life. She had long black hair and long pale legs and she wore a summer dress despite the cold and a fur coat over the dress. She carried a purse. It was hand-threaded with beads that formed into the image of a mockingbird. It was French, and expensive. Her gaze passed over the office, taking in the small dirty window that no one ever cleaned, the old pine hatstand on which the varnish was badly chipping, the watercolour on the wall and the single bookshelf and the desk with the typewriter on it. There wasn't much else to look at. Then her gaze settled on me.

Her eyes were grey. She said, 'You are Herr Wolf, the detective?'

She spoke German with a native Berliner's accent.

'That's the name on the door,' I said. I looked her up and down. She was a tall drink of pale milk. She said, 'My name is Isabella Rubinstein.'

Her eyes changed when she looked at me. I had seen that look before. In her eyes clouds gathered over a grey sea. Doubt—as though trying to place me.

'I'll save you the trouble,' I said. 'I am nobody.'

She smiled at me. 'Everyone is somebody.'

'And I do not work for Jews.'

At that the clouds amassed in her eyes and stayed there but she remained calm, very calm. Her hand swept over the room. 'I do not see that you have so much choice,' she said.

'What I choose to do is my own damn business,' I said.

She reached into her handbag and came back with a roll of ten-shilling notes. She just held it there, for a long moment.

'What is it about?' I said. At that moment I hated her, and that hatred gave me pause.

'My sister,' she said. 'She is missing.'

I had two chairs for visitors. She pulled one to her and sat down, crossing one leg over the other. She was still holding the notes between her fingers. She didn't wear any rings.

'A lot of people are missing nowadays,' I said. 'If she is in Germany I cannot help you.'

'No,' she said, and this time there was tension in her voice. 'She was leaving Germany. Herr Wolf, let me explain to you. My family is very wealthy. After the Fall our assets were seized, but my father still had friends, some even amongst the Party, and he was able to transfer much of our capital to London. I myself, and my mother, were both allowed to leave the country legally, and my uncles continue the family's continental operations in Paris. Only my sister remained behind. She is young, younger than me. At first she was beguiled by their ideology; she had joined the Free Socialist Youth before the Fall. My father was furious. But I knew it would not last.' She looked up at me, with a half-smile. 'It never does, with Judith, you see.'

All I could see was the money she was holding between those long slim fingers. She moved the roll of notes back and forth, idly. I had been penniless before, and poverty had made me stronger, not weak, but that was in my former life. My life was different now, and it was harder to be hungry.

I said, 'So you arranged for her to leave.'

'My father,' she said quickly. 'He knew men who could smuggle people out.'

'Not easily,' I said.

'Not easily, no. Not cheaply, either.' Again that half-smile, but it flickered and was gone in a flash.

'How long ago was that?'

'A month. She was meant to be here three weeks ago. She never appeared.'

'Do you know who these men were? Do you trust them?'

'My father did. As much as he could be said to trust anyone.'

Something jogged my recall, then. 'Your father is Julius Rubinstein? The banker.'

'Yes.'

I remembered his likeness in the Daily Mail. One of the Jewish gangsters who grew rich and fat on the blood of the working man in Germany, before the Fall. His like always survived, like rats abandoning a sinking ship they fled Germany and re-established themselves elsewhere, in clumps of diseased colonies. They said he was as ruthless as a Rothschild.

'Not a man to cross,' I said.

'No.'

'Your sister … Judith? She could have been captured by the Communists.'

She shook her head. 'We would have heard.'

'You think she was brought to London?'

'I don't know. I need to find her. I must find her, Herr Wolf.'

She put the roll of notes on my desk. I left it there, though whenever I looked at her the notes were in my field of vision. The Jews are nothing but money-grubbers, living on the profits of war. Perhaps she could see it in my eyes. Perhaps she was desperate. 'Why me?'

'The men who smuggled her here,' she said, 'are old comrades of yours.'

There was nothing behind her eyes, nothing but grey clouds. And I realised I had misjudged Fräulein Isabella Rubinstein. There was a reason she had picked me, after all.

'I do not associate with the old comrades any more,' I told her. 'The past is the past.'

'You've changed.' She said that with curiosity.

'You do not know me,' I said. 'Do not ever presume to think that you do!'

She shrugged, indifferent. She reached into her purse and brought out a silver cigarette case and a gold lighter. She opened the case with dextrous fingers and extracted a cigarette and put it between her lips. She offered me the open case. I shook my head. 'I do not smoke,' I said.

'Do you mind if I do?'

I did mind and she could see it. She flicked the lighter to life and wrapped her half-smile around the cigarette and drew deep, and blew smoke into the cold air of my office. A draught came in through the window and though I was dressed in my coat I shivered. It was the only coat I owned. I looked at the money. I looked at her face. She was nothing but trouble and I knew it and she knew I knew. I had no business hunting for missing Jews in London in the year of our Lord 1939. I once had faith, and a destiny, but I had lost both and I guess I'd never recovered either. All I could see was the money. I was so cold, and it was going to be a cold winter.

*

When the Jewish woman departed, Wolf sat there for a long moment staring at the money. The smell of her cigarette hung in the air, rank and nauseating. He could not abide the smell of tobacco. Outside the window it was already dark. The cold clawed at the windowpane. Below he could hear the market shutting, the sound of whores sashaying into the night. His landlord's bakery on the ground floor had already closed for the day. He stared at the money.

He pushed the chair back, stood up and took the roll of notes and put them in his pocket. He set the chair back and went round the desk and stood looking at his office. The painting on the wall showed a French church tower rising against the background of a village, a field executed in a turmoil of brushstrokes. Three dark trees grew out of a tangle of roots rising in the foreground of the church. On the bookshelf, a personally inscribed copy of Fire and Blood, Ernst Jünger's memoir of the Great War, sat next to J.R.R. Tolkien's The Hobbit, Madison Grant's masterpiece of racial theory, The Passing of the Great Race, a collection of Schiller's poetry, and a row of Agatha Christies.

There was no copy of Wolf's one published book. He stood looking at the shelf. He had saved only a handful of the collection of books he had amassed before the Fall. Their loss ate at him. But he had already lost so much. He went to the hatstand and put on his hat. His shadow fell on the wall like a dirty coat. Wolf opened the door and went outside.

*

Berwick Street, Soho, on a cold November night. Electric lights cast the pavement in a gloomy glow. The dirty bookstore was open. Whores loitered outside. He stood under the awning of the bakery when his landlord came out of nowhere like a Jew in the night.

'Herr Edelmann,' Wolf said.

'Mr Wolf,' Edelmann said. 'I am glad I caught you.'

He was a short, pudgy man with hands and a face as pale as flour. He had a furtive manner. 'What is it, Herr Edelmann?' Wolf said.

'I hate to bother you, Mr Wolf,' Edelman said. He wiped his hands at his sides as if he still wore his apron. 'It is about the rent, you see.'

'The rent, Herr Edelman?'

'It is due, you see, Mr Wolf.' He nodded, as though confirming something to an unseen audience. 'Yes,' he said, 'it is due some days now, Mr Wolf.'

Wolf just stood there and looked at him. The baker hopped from leg to leg. 'Cold, isn't it,' he said. Wolf watched him in silence.

'Well,' Edelman said finally, 'I hate to ask, Mr Wolf, really I do, but it is the way of things, isn't it, it is the nature of the world.' His whole stance seemed apologetic, but Wolf wasn't fooled. There was a flash of steel underneath the baker's quivering exterior. Wolf didn't deign to reply. He reached into his pocket and pulled out the wad of money and peeled off two ten-shilling notes, watching the baker's eyes all the while. He returned the rest to his pocket. He held the money in his hand. The man seemed hypnotised by the money. He licked his lips nervously. 'Mr Wolf,' he began.

'Will this do, Herr Edelmann?' Wolf said. The man made no move to take the money, waiting for it to be offered. 'It is the nature of the world that evil exists,' Wolf said. 'It is not money that is evil but the means to which it is put to use. Money is an instrument, Herr Edelmann, it is a lever.' He held the money steady in his fingers. 'A small lever to move small people,' he said. 'But give me a large enough lever and I would move the very world.'

'That's very interesting, Mr. Wolf,' Edelmann said. He was still looking at the money. 'Do you wish to pay for a month upfront?'

Wolf handed him the notes. The baker took them and secreted them about his person.

'I would require a receipt,' Wolf said.

'I will put one through your door.'

'Make sure that you do,' Wolf said. He touched the brim of his hat, lightly. 'Guten abend, Herr Edelmann.'

'Good evening to you, too, Mr Wolf.'

Wolf walked off and the baker disappeared into the darkness like a shadow. There had been too many dark streets and too many shadows, melting into the night, never to be seen again. Wolf thought about Geli. There had not been a day gone past when he had not thought about Geli.

The whores were gathered in Berwick Street. They stood light as shadows, mute as stone. Wolf hesitated as he passed nearby. With his approach the girls grew lively, and raucous laughter welcomed Wolf's approach. In a passageway between buildings a fat whore was squatting with her back to the brick wall, crapping. He caught a glimpse of her pale loose flesh, her garments round her ankles. 'Looking is for free,' someone nearby said. A girl no older than sixteen flashed him a smile. Her lips were red, set in a white, made-up face. Her teeth were small and uneven. 'Hey, mister,' she said. 'You want a quick one?' She spoke English with an accent he knew well and with a vocabulary learned from reading cheap novels.

Wolf said, 'I've not seen you here before.'

The girl shrugged. 'What about it,' she said.

'You are Austrian,' he said, in German.

'What about it.'

In the alleyway the fat whore farted loudly and laughed as her bowels emptied steaming onto the cold flagstones. Wolf averted his gaze.

'You should find another line of work,' he told the girl.

'Go to hell, mister.'

Underneath the streetlights a few johns were already passing, eyeing up the girls. In a few hours trade would be brisk. Another whore approached them. She was someone Wolf recognised, Dominique, a half-caste girl. 'Pay no attention to him,' she told the new girl. 'It's just Mr Wolf's way with us. Isn't it, Mr Wolf?' She smiled at him. She had light brown skin, red lips and cool eyes. The new girl looked at Wolf uncertainly. He knew the expression in her eyes. Trying to place him. When he had first come to London many had known his name. Now there were precious few who cared. 'Fräulein Dominique,' he said, politely.

'Mr Wolf.' She turned to her sister in trade. 'Mr Wolf never goes with one of us.' Her smile was mocking. 'Mr Wolf only ever looks.'

The Austrian girl shrugged. There was a dull look in her eyes. Wolf wondered how she had come to London, what she had escaped from. He could imagine it well enough. He bore the scars of such a departure himself. 'What is your name?' he said.

'It's Edith.'

He touched the brim of his hat. 'Edith,' he said.

'You can fuck me for ten shillings,' the girl said.

'What Mr Wolf wants,' Dominique said, 'it would take more than a ten-shilling whore to satisfy.'

Wolf didn't answer back. There was never a point, with prostitutes. In Vienna before the War he had seen them on the Spittelberggasse, each girl behind a lighted window, some young, some old, some sitting, some standing, some doing their hair or smoking cigarettes. For a long time he had walked past the low one-storey houses, with his friend, Gustl, watching them, and the men who came to use their services, how the lights in the rooms would be turned off once a deal was concluded. One could tell by the number of darkened windows how trade was going.

The fat whore—her name was Gerta—had emerged from the alleyway pulling up her undergarments. She waved at Wolf cheerfully. He repressed a shudder of revulsion. The young girl, Edith, had lost interest in him. A couple of men on the other side of the street were looking at her with interest, cattle traders examining livestock. They called to her and she was gone, into the shadows. The half-caste Dominique was suddenly very close. She was taller than Wolf. Her lips were by his ears. Her breath warm on his skin. 'I know what you want,' she said. 'I can give it to you.'

There was a strength about her; he feared and desired what she could sense in him. Her hand reached down and pressed painfully on the front of his trousers. 'Yes,' Dominique murmured, 'I know. And I would enjoy doing it to you, too.'

For a moment he was frozen; she had snared him with lust; what the Jews called the 'evil inclination', the yetzer hora. But he was stronger than her; stronger than that. He removed her hand. 'I'll thank you not to touch me again,' he said. Dominique looked him down and up. Her lips curled and then she too was gone, into the night. Wolf walked on.