Leland studied Creative Writing and Ethnic Studies at San Francisco State University where he discovered the enormous possibilities of poetry, experimentation, and critical theory. He eventually earned an MFA in Writing from Columbia University on a merit fellowship. He has published fiction in Open City, Fence, Dark Sky Magazine, Drunken Boat, and Monkey Bicycle, among other literary journals. He is also the project director for an upcoming literary event series, Phantasmagoria, for which he received fiscal sponsorship from the New York Foundation for the Arts. He lives in Brooklyn, NY.

Is Epstein a despicable man?

He's certainly trying desperately at something. When his wife disappears he's frantic to talk to his daughter. But what can he tell her? There must be a reason and he's all but sure about the gruesome answer. Can he protect Sylvia from the truth, from her terrible lineage and, ultimately, from himself?

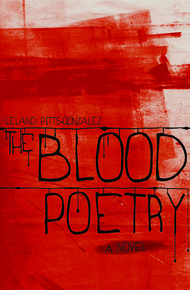

Off-beat and sordid,The Blood Poetryis a twisted, yet honest look at our desire to connect with others and the ways in which we are often stymied by our own efforts to get closer. Epstein is a curious mix of monster and romantic struggling to maintain a shred of dignity in his dingy, beat down world.

This book is published by Raw Dog Screaming Press who are known for giving us fantastic books from a diverse range of authors, so I am not surprised by this gem of a book coming out of this press. All I can say about Leland's writing is it has the viscosity of blood and will keep you licking the words off every page. – V.Castro

"The Blood Poetryis a brilliant, brutal assault of a novel—raw, twisted, and compulsively readable."

– Shelf Unbound"From some forgotten box under Patrick Bateman's bed comes this rat rod of a novel: ragged, supercharged and wildly inappropriate. A Bataille sitcom full of meat and mommies. The main pervert's agony would be harrowing if it didn't also happen to be very funny."

– Grace Krilanovich, author The Orange Eats Creeps"Leland has such a unique voice; he uses language in such a surprising and original way. I love the echoes of the truth: a mother sucking the blood out of her son, his sexuality and his wife, only literally. This is so smart and fascinating. I have never read anything like this. By being consistent with his characters, adopting more of a traditional narrative structure, and weaving in and out of the "real" and the imaginary with consistency, he really makes it work.It is beautiful! Unflinching!"

– Rachel Sherman, author The First Hurt"If one new horror book out there embodies the intelligence of great literary fiction with the best elements of psychological horror, The Blood Poetry has to be it...paragraphs screamed, asking to be taken out and plastered on gigantic billboards so everyone could enjoy their humor, brutality or blood-splattered philosophy."

– Horror Talk"Pitts-Gonzalez tears apart what we know of structure and character, narrative and theme ... has brought to us his vision and his is uncompromisingly surreal and vicious in its value of entertainment."

– Shock HorrorListen.

I traipse no I run no I sprint—a fat, impotent ghoul sprung straight from the cellar of my childhood home—past the pregnant girl with five skeletal children and the nun and the synagogue with its windows stoned through and I'm headed directly for my daughter, Sylvia, at her school where she's stationed with classmates of wannabe punks and black boys with their heads shaved and every one of them, apes, gushing out their hormones as I sprint to the edge of the Earth where Sylvia studies the canon of our national literature that I'm desperately trying to forget. My mind circles around the memory of my wife, Abby, and I must tell Sylvia everything, everything, because our brief lives depend on it. My heart races, so I halt and I bend over and gasp, spilling the life-force straight from my gut as I straighten up and focus on Sylvia in the baseball field posed before the sun as if I were destined to paint her into eternity but, my dear Satan, I will never be an artist. Our Earth has come to this. I must confess everything. Our clan's terrible history pierces my forehead from the inside-out, but my idiot right hand, on its own, betrays me and covers the spiritual hole in my head. It's hot and I'm drenched with sweat and quickly, dumb fuck, quickly, decide whether or not to tell Sylvia about all the debauchery of our clan and she's right over there ahead of me as if, even, I would dare to touch her. My tongue is a slug desperate to peek out, so speak loudly of the femurs in our dark present, of Abby, my missing wife, of what happened and may never be resolved, never, and then Sylvia—my beautiful, young offspring—sees me and grimaces as if she's embarrassed of her fat, impotent father, but I'm here, Sylvia, right here but she has no idea what's coming for her.

"Why are you fucking here?" Sylvia prods me with her curmudgeon stare and scans the baseball field for all the boys streaming their sex straight into her as she turns this way and that way, trying to hide from the air and all the boys and the janitors, too. "Shouldn't you be teaching or something? I thought you had a job." She cradles her teenage, wondrous and big head on her shoulder with that black hair cascading down, down, as she tries hard and fast to block the shock and the shame of her father. (Think here: fat motherfucking father.)

"I called in sick, Sylvia. I have to tell you something." I have it all on the tip of my tongue and, but I shift my heft, perspire, try to stop my body from aging. I'm balding and overweight and out of breath, and under my tongue are scandals that even I won't admit to myself. Just then, a bruisy-looking dude with dyed hair laughs and laughs and stares at Sylvia's butt as if he's a pilgrim straight out of hell. I glare deeply through him because, not so far away from my conscious mind, I'm a killer fashioned from blistering and religiously sharpened titanium.

"Talk to me in front of my friends? Really, Papa?"

"No, not in front of your friends. Come, daughter, let's walk."

"Couldn't it wait till I got home?"

I open my mouth to let it all out and implicate me and her undead grandmother right then and there. I say absolutely nothing once again, god bleeding fuck, even though I know I must. The sun's plasma pummels us and tries to force me to secrete the muck of my ancestral history that hovers like some nuclear fallout over us. I had vowed to protect Sylvia from all of this since the day she was born; to shield her from her grandmother, the bitch progenitor; to shield her, period, so I could give Sylvia the gift of a simple, tranquil life. But Abby, Sylvia's poor mother whom I tried to save, vanished last night and I know about the whole thing—or maybe I don't know or I never wanted to—so I stand beside Sylvia, the simpleton that I am, as her ape classmates giggle under their breaths.

We walk and the sun blasts us until we're speechless, so we traverse the strange and unnamable spaces between here and there. Around us are all the damned items that ever existed—newspapers and trinkets and shoes, etc., and skittering rats and water bottles and old women underwear and two gallons of white paint, etc., and birth certificates and sloughed-off fingerprints and fungal toenails, etc., and that damned, blasphemous heaven.

"So what is it, Papa, tell me, will you?" She looks directly into me as if she knows it's the end of it all, but I deflect her with my thoughts, not wanting to and—

"Maybe we should get inside first—somewhere to protect us from the ultraviolet rays and are you hungry are you famished?"

"I guess. I could go for something." She tilts her head down. Her super-straight black hair manes over her shoulders like liquid and she wears expressions well; her forehead defined and wrought and a few blemishes on her innocent, thirteen-year-old face. I look at her from my periphery and I know she's tall for her age; looks more like her mother, thank god, and her gait is free like her thoughts are free and the breeze messes with us, reminding us that we'll never be alone. The roads are devoid of any cars for some reason, but a fire truck does whiz by us straight for the fire in my brain. You're a wonderful daughter, Sylvia! I want to bellow until my lungs collapse.

"Let's go to Malfeasance and Human Hair, then," she says with a stammer. "They do have great burgers." We stop and examine each other on this desolate sidewalk for a brief moment—much, much too brief—because, even though there's a father-daughter kinship between us, nothing will ever be the same.

"Yeah," I mutter, "let's go."

We enter Malfeasance and Human Hair and sit near the window and all the invaders on our dinner scan us through and through. I contemplate these hooligan customers and imagine what my brutal confession will sound like to Sylvia, and am deeply sad about my broken promise to the daughter. I vowed to protect her from all harm and all danger. She is absolutely everything to me.

Sylvia reads the menu, not knowing what to think.

It's the sheet between our sexes.

"Can I help you guys, or do you need another minute?" the waitress asks, chewing on a pencil destined for a weird purgatory where they store saliva and all the dead waitresses.

"Do you know what you want, Sylvia, do you?" I have the expression of a caveman that even a retard could decipher. I rub my palms together, sweaty and all, and just tell her, I think, and tell her, but my clemency won't come as easily as a priest exorcising some possessed hooker. All I can do is scrub my hands together—scrub, scrub, and maybe my conscience will get the best of me.

"I guess I know what I want," she says.

The waitress grinds on the wrecked pencil.

"Go ahead, then," I say.

Sylvia explodes with the energy of a newborn because this may be her last and best chance at immediate gratification and any simple, naive pleasure for decades to come. "OK," she says. "I'll have the Genius Meat with lettuce and tomato and Asphyxiation and a Perfunctory Shake, thick as possible, please!" Her grin is a lightning bolt and she appears to be like any other thirteen year-old girl.

"And for you, sir?" The waitress is blonde and disturbed, has a heft that is mildly becoming, and her omnibus bosom dominates my gaze.

"I'll have Slaughtered Chunks with Oozings on a Bun. Lots of friggin bacon. And give me potatoes."

"Anything to drink?"

"A hoppy beer, no wait," and my mind wades into the preteen dates I had when I groped the first of very few boobs, although it's not the semen I remember, but the taste of cherry cola from the fountain! "I'll have a cherry cola straight from the fountain," and I pound the table with my man fist, but it hurts because I'm aging and decrepit and I can feel the arthritis already penetrating every cell in my body.

Sylvia and the waitress are taken aback; that, I can clearly tell.

"You got it," the waitress says, shaking her brain of low IQ.

The offspring and I examine each other from across the table—eye to eye—and we both smile and frown. I look at the tabletop because I'm ashamed, and then the floor tile 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 (a cracked one) 7, 8, 9, (a shattered one) and deflect my vision again to some scribble on the wall in the darkest marker that reads I love you, Papa, forever and ever and ever!

Now I'm paranoid, swiveling my head back and forth, because I believe I'm going to be found out for who I am, and what I've come from. It's the crowded dumbing-down in the restaurant that plagues me greatly with all their groping little eyes; the group of wig-wearers at the end of the counter and the woman with the crooked gold wig staring at my forehead as if GUILT were branded there; the old dude with a pompous head of hair and a cape who reminds me of vampire lore; and the mutant child with the long mane that makes him look like a woman, but mostly it's his penetrating blue eyes; and, suddenly, from the looks of it, I'm definitely in deep, deep trouble, like there's a lurking drool around the corner of it all; the smoldering meats and greases sprinkling the walls intentionally; me terribly afraid of Sylvia and her response to my lame verbiages of love and devotion (right), but really I'm afraid of the alphabet under my tongue that spells out our blasphemous, unspeakable ancestry. And that, up until today, was hidden from my daughter.

"L…listen," I stutter, which is weird because I haven't stuttered since Professor Applebaum—Mother's vampire love and dead fucker—invaded my childhood those many terrible years ago…

"What is it, Dad? Spit it out." She places her hands on the tabletop, reaching for me, and we join hands like a real family for once, but I retract.

Ah! I look for snowflakes in the fluorescent lighting, wonder if angels live in the electrical grid, look at the black marker scrawl of some child (I love you, Papa, forever and ever and ever!), try forever to forget about my wife but never will, and the cars with the leaking zombies screech into the parking lot to bring us the nastiness and omens. "Your mother…left us."

"She's dead?!"

"No, no, no. She's just…missing, is all," I lie, "and there's no need to get all worked up, OK, and I see you're getting concerned and no, no, don't tear up now Sylvia and, oh jeez, I'd better just tell you—"

I have finally betrayed her.

"Tell me what?" she asks.

I run my fingers through my thinning hair. There's got to be forty-plus people in the joint reading my pimply soul as if it were scripted in Braille.

"I think maybe she was on drugs, Sylvia, it was the drugs that were her downfall!"

"She's not on drugs, asshole. You were on the pills and the alcohol and the porn most of my life."

"Shit," I squeak. "I did try to shield you." I palm my forehead as if I could baptize myself with my own spit.

"I'm almost a woman, Papa."

"It's the almost that kills me." I stare down the waitress to get her attention, fixate on the flab of her noxious ass that must taste awful on the toilet bowl, and she finally comes over.

"Can I help you, sir?"

"Yeah, can you bring the Meat Spigot?" I'm already drunk on the idea and the exclamation points that will be emblazoned in my shit-cocked brain, but I just can't tell Sylvia, no, I just can't.

"You don't want the Slaughtered Chunks anymore?"

"I do, waitress, but I also want the friggin Meat Spigot so I can escape from all the hobos in this joint and all of the zombies in my home," I exclaim, and often dream of the drunkenness of cooked-tubular-robust-beef-waitered-in-whiskey-from-the-spigot, because it's a sumptuous dream, yes, something like oblique sex, cock-purple and reality, etc.

"Meat Spigot it is, then." She walks off and mutters under her foul breath, "Fucking drunk."

I refocus my attention on the one daughter I will ever have.

"We have to look for her, Papa. She's missing missing?"

The Meat Spigot comes to the table adorned with a gold handle and I put my mouth up to its mouth and draw on the deep, red blood of it all.

"How the hell can you get drunk right know on fermented meats?!"

"Oh, bacteria, Satan…"

"Waitress?" my daughter exhorts. "Can you wrap all of our stuff to go?"

"Bud?" the waitress asks of me, still gnawing on that erect and honed-down pencil.

I slurp and do no good whatsoever and the acid reflux is upon me, indeed and, "I guess so, but can you fix me a container of Meat Spigot Exclamation Juice?"

"Of what?"

"Bring me the fermented tubular meats," I say with a grinding-of-teeth sound, "OK?" I ask, "Are you bosomy enough?"

The waitress leaves, and…

"We gotta go, Papa.

"Really?"

"Give me your fucking cell phone. I can't find mine. I lost it, fuck."

I give her the phone and implicate myself in my thoughts and I must've been a shriveled loon believing I could be a good father when I conceived Sylvia, having an undead mother, and all, who's tethered between tranquility and murder. I slop down the alcoholic meats to forget the world and, "Shit, this is good! Whiskey, dreams!"

"Oh, just great. You don't have any phone numbers in here."

"I have no one to call except you and your mother."

The waitress brings the packages of food. "Here's your bill," and walking away, she mutters, "fucking asshole."

"Give her the money, Papa."

I fork over a couple of notes and we get up and Sylvia speed-walks with a wispy gait and, so, I follow her every moment that I can, but…

"We gotta get home, like yesterday, Papa, like come on, come on, we gotta fucking find my phone so we can make calls to all my familiars and find Mom to bring her back to me because I don't have anyone else!"

We speed-walk through the parking lot, me following her, toward my insidious vehicle which has been parked there for days and, just then, a one hundred-year-old black hobo—his socks mended to his gangrenous skins—hurls pennies across the pavement toward us like they're his last and most important thoughts.

"Shit," I exclaim. "Look, a penny, 1938, Sylvia! The year your grandmother was born!"

I discover, then, that the black hobo is looking straight up and harbors resentment against outer space, and he must be hugging his freakish dead mommy in his mind, and he wishes he was suffocating in some deep and anonymous grave.