Nerine Dorman is a South African author and editor of science fiction and fantasy currently living in Cape Town, with short fiction published in numerous anthologies. She is a contributor to the Locus Award-winning Afro-Centered Futurism in Our Speculative Fiction edited by Eugen Bacon (Bloomsbury, 2024). Her novel Sing down the Stars won Gold for the Sanlam Prize for Youth Literature in 2019 and The Percy Fitzpatrick Award for Children's and Youth Literature in 2021. Her YA fantasy novella, Dragon Forged, was a finalist in the Sanlam Prize for Youth Literature in 2017, and she is the curator of the South African Horrorfest Bloody Parchment event and short story competition. Her short story "On the Other Side of the Sea" (Omenana, 2017) was shortlisted for a 2018 Nommo award. Her novella The Firebird won a Nommo for "Best Novella" in 2019. In addition, she is a founding member of the SFF authors' co-operative Skolion.

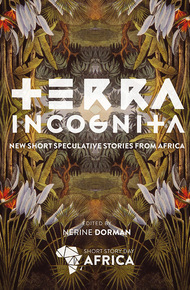

Contained within the pages are stories that explore, among other things, the sexual magnetism of a tokoloshe, a deadly feud with a troop of baboons, a journey through colonial purgatory, along with ghosts, re-imagined folklore, and the fear of that which lies beneath both land and water. Terra incognita. Uncharted depths. Africa unknowable.Nineteen new short speculative stories from the fringes and hidden worlds of Africa.

"Most of the stories in these two volumes articulate the relationship between globalized first-world culture, with its expectations of fiction, genre, and style, and various African localities, with their hardly pristine cultural specificities. Most of them reek of history and seem to be cast in a post-apocalyptic mode. They are not post-apocalyptic in the way British cosy catastrophes, Hollywood blockbusters, and incessant zombies have taught us to think of what comes after the end of it all. They are documents of the postcolony, and as Mad Max: Fury Road's Namibian locations remind us, that is also, and always already, the post-apocalypse.

They are what comes next."

– Mark Bould, LA Times review"SSDA is a gift to lovers of African fiction. Ever since two of their writers were shortlisted for the Caine Prize—one went on to win—we've relied more and more on their writing contests and anthologies to introduce us to those little known African writers doing amazing work.

Titles like "Leatherman,""What If You Slept?,""Ape Shit," "In The Water," "The Corpse", "I am Sitting Here Looking at a Graveyard" promise a whole lot of hair-raising andheart-stopping fun."

– Ainehi Edoro, Brittle Paper"Gone is what Chimamanda Adichie feared – the tale of monolithic Africa that ignores the variety of experiences and the continent's diverse cultural heritage to focus only on shared experiences of poverty, slavery and unrest. This anthology boldly eyeballs Africa's unfathomable depths, mirrors that depth in the skills and imagination of its nineteen contributors, and dares all comers to restate what they think is African in literature."

– Tinuke Adeyi, WaWa Book reviewLEATHERMAN, by Diane Awerbuck

For Clare

It was not that she was a prude. Joanna had just not found anyone she liked enough to relieve her body of its tight-wadded burden—the bud, the bouquet, the burning bush of her maidenhead. She wanted an expert, a light-fingered someone with a cunning tongue, but the hopefuls who knocked on the door were boys too young to know better, or her father's hairy, beery friends.

It was not the hair, really, either—it was the geography of it. Silverbacks, tonsures, furry-purry fright wigs: Joanna had refused to run her fingers through them all. But, more than that, it was the men's discomfort with their own topography that dampened her passion, the way one sucked in his gut when he passed her in Hatfield Street, or another whistled through nasal topiary when she skirted him on the steps.

And time passes more quickly when you're busy, as anyone who's ever attended a sickbed will say. Soon she hardly thought about her sanitary state. At Allure she researched features for the other women, invariably older, pencil-skirted, divorced. They smoked but never ate, and spoke in deep voices about the Dirty Thirties and robbing the cradle. Joanna couldn't see the point of younger men. Was it so much to ask, for someone she liked, who liked her too? She looked for him on the horizon, wished for him in the evening on Venus's unvarying machinery—the big-night star, the morning-after star—which should by rights have watched over her.

Joanna wasn't an idiot: she had known that a big city meant a certain amount of loneliness, but the Mother City was harder than she had imagined when she was back in Kimberley, mooning from the window of matric. She was unprepared for the carelessness of Capetonians, for sex-as-premise, for the difficulty of comprehending the unspoken rules, like iron filings rustling untouched on a sheet of foolscap. By the time you worked out the magnet's movements, it was too late.

The ticket to YDESIRE had been comped to Allure for publicity. "Oh, please. Take it," Siobhan had told her. Joanna found her dyed hair difficult to look at, brickish, hard against the hand. Siobhan breathed neglect and necrosis: her stomach was digesting itself. The editor fluttered her starved fingers. "Another fucking art event."

During her lunch hour, Joanna had gone to The Emporium, searching for an outfit that would make her look like the girls she spied on in Mister Pickwick's: thinnish, hungover, imperfect girls who would skinny-dip in waterfalls with your boyfriend or produce large-eyed love-children with French seamen. They smelled of dirty panties and oily scalps, of snail-slick contamination, of sliding focused and impervious to some decided finish. Joanna in her slabbed flesh was unpierced, unmarked, a concentrated negation. She had looked under the rock and seen its workings. This was her last chance: really, the final countdown.

SOFTSERVE 4, said the invitation. Disbelieving, Joanna kept taking it out of her bag, like a guidebook. YDESIRE. The map of the Castle's innards was spread in pink on the reverse; the main building itself was an icon, an areola, a stamp for a club that had never let her in. Joanna imagined the pockmarked walls hung with fairy lights for this one bright night, translated at the witching hour. Tonight she would dance on the heathen grass, twist under the tinselly stars, stretch out her sore back that had been slumped by plainness and office chairs. In a few years, Joanna knew, she would have a widow's hump. A Windows hump. If this doesn't work, I'm going to be a librarian, she told herself, as she made her way to the changing room with its corrugated door like a rocket ship and its promise of astral travel.

The clothes draped over her arm were doll-sized, made for aliens. She should have been used to it from the magazine (GET HER LOOK!) but it still took her by surprise, the Asian cookie-cutter that she saw descending on the dough of women's bodies. She began to struggle into a pair of animal-print pants. What had her mother called them? Pedal-pushers, like something out of an Archie comic. God, it was hot in here. Nothing worked, as if the shop was a stage set and backstage had been abandoned. Even the ceiling was still being built. Joanna scrutinised the digestive tract of the ventilation shaft—segmented, silver—and tugged at the pants. How reflective was it? Were the stick-insect salesgirls watching her wriggling against the seams?

She thrust her knees down into the pants like a drum majorette, and there was a ripping sound.

Joanna peered between her legs, a giraffe at a watering hole.

She had torn the material hymen.

She wouldn't be able to get them off again, either, a baboon with its paw caught in a biscuit jar. Joanna groaned and hauled the material over her rump in one last yank, and the teeth of the zip came to rest against her stomach. They burned cold as dry ice. She would have to buy the things now, and cut them off her. Not a drummie or a giraffe or a baboon: she had turned into some composite creature, tagged with metal and flagged with cloth.

But, surely, in a million other unseen changing rooms, her sisters were undergoing the same transformation. From the pods they would emerge the same light and laughing butterflies. She would go, she would, to fly in their rabble, to be flung against the smouldering streetlights. So she had no one to go with, and no car to get there. Big deal. Joanna hitched up the pedal-pushers and turned to look at her scrumpy, lumpen arse. She didn't need to sleep. The Pickwick's girls didn't. She would stay out all night and in the morning she would take the train back out to Observatory before anyone woke. She even had the timetable in her silly backpack, next to the roseate sprawling invitation. In the station the trains lodged, cold as revolvers, until four forty-five when the hollow-tipped passengers filled their chambers. Tonight they could wait for her: she had been waiting for them her whole life.

Joanna stayed late after work and did her make-up in the unisex bathroom. She could have asked the stylist to help her—Siobhan often had her hair done before a night out, wheedling, "Oh, darling, won't you give me a quick blowjob?" But at the last minute, Joanna had lost her nerve. She checked her tiny backpack and patted the carton of Siobhan's dribbly drinking yoghurt, like semen, that she'd fossicked from the office fridge.

The evening in the city was kind, the air soft and undecided, blowing possibility up from the harbour, sweeping the streets of bland diurnal debris. Behind the thick, whitewashed walls were secret gardens, art exhibitions, law courts, hotels. For the first time they were hers. It made Joanna's heart hurt with pleasure. Every pavement coffee-drinker was a Barbara Cartland book cover; every dreadlocked backpacker was a boy she might kiss. She bounced through the Company's Garden with its raddled rose bushes, its glue-sodden street kids and bowed businessmen, circles of anxious sweat under their arms. Men watched her from the corners of their eyes as she swung her leopard-print hips, but she had wanted them to—hadn't she? It was a rule of the street that the more revealing your clothing was, the less attention you got.

The times Joanna really felt frightened were when she was wearing jeans and a long-sleeved shirt: the lack of willingness was what turned men on. They called to her from swerving, dented taxis, grabbed at their crotches, followed her in groups. "You look like a nice time," they told Joanna. Someday she would meet her man with his knife, but tonight her feet were springy against the curb, as if she was on the starting block of some magnificent race. Joanna felt the energy zing up through the bones of her feet, her knees, her thighs, and the hot pot of her pelvis: predestination.

She was nearly there. She would take a shortcut at the road that went past the Shack and the Mexican restaurant and that ridiculous showroom that sold only red sports cars. The path was mostly through grass—a meadow, really, a weedy overgrown plot surrounded by slanting high-rise reses. You never saw the students: inside, their dank and glugging drains; outward, the glassy facelessness.

Here the field was, knee-high and singing at sundown. Somehow the long, blond grass had escaped the severe manicure that was the sign of the city council. At the beginning of summer, the men were everywhere. They came with their reek of petrol and their masks: often at sundown, when rush hour was over, they set up their cones and tape on the highway. On Devil's Peak you saw them waxing a bare strip around the forest so that the scabbed pines oozed peaceful and resinous under their bark as night came on. The next day, from her Metrorail carriage, Joanna saw the shorn places within the city bounds as well, green lungs collapsed and spent, empty as wheat fields after the harvest. One man went to mow, she sang softly to herself. He went to mow a meadow. When they came too late there were fires, the flames creeping down the mountain every Friday evening until they made a cemetery of the city and the countryside around it. Joanna witnessed the empty tortoiseshells from the morning train too. NOW SEE WHAT YOU'VE DONE! begged Bambi on the signs blurred with passing.

Now she stopped, the blood pumping so hot in her feet she wanted to kick off her shoes. A whole field of grass, intact. The seeds chorused and swayed, interspersed with bunny-eared stalks. Joanna felt the medieval pull, boys under haystacks, bladders of cider in the end-summer heat, the unified rustling of the parched grass. And—oh, God—the smell. Joanna looked around to see if a soul would appear at a res window, but she was alone. She put her face closer to the grass and felt the saliva bursting under her tongue. She wanted to lay her cheek on the sweet earth or nuzzle the soil, like an astronaut home from the moon.

But up close the ground was hard and scabbed. Joanna squinted at it in the dusk. There were bricks here—the abandoned foundations of a building. The bricks were dark red, pentacled, Mayan. Animals had pissed on the remains: cats, and people, marking their invisible territory. She smelled it, quest and threat, the pheromonal tattoo.

Joanna stood up too soon, and the blood sang in her head. She inhaled one last time—surely this air came from somewhere else, some other good and happy time—and then she carried on up the road that would take her into town.

It was a mistake, she saw right away, from the banner over the Castle doors: FEELS SO GOOD INSIDE. Her pants, her make-up: awful. Everyone, everyone, was there in groups: the Pickwick's girls with their faces streaked with silver paint and their chests bare. They had been hired to stand at the entrance and feed punters shots of tequila. Around their necks were strings with plastic tot cups that twitched and dribbled between their boobs. Joanna couldn't look away from those puckered nipples, those sides of flesh. All you can eat, she kept thinking. All you can eat. She wanted to run her fingers—prrrp—over their xylophone bones, and tap their hollow insides.

Inside was worse: sacrilegious. The open space of the parade ground had been blanketed with art installations and the hideous merriment of bunting, like a drunken uncle singing Happy Birthday. People were jostling along the pathways in moonlit groups, peering at the pieces. Her ears hurt: in her back teeth the generators grumbled. The human shrieking against the boom of the music was panicky, hysterical, people jumping on each other's backs, sticking their tongues down each other's throats. Joanna had read that your mouth was sterile when you woke, but even that seemed unlikely. How did people ever kiss or hold hands? Touching spread a thin layer of filth over everything. The fingernails of ordinary men made her shiver. Joanna kept her prissy hands in her pockets, sure that her purse would be lifted by a lantern-eyed lingerer. Contact was contagion.

She tried to choose a path out of the babbling maze, but was stopped in her tracks by a giant moon. There were people inside it like invading ants, feelers twitching, papering over its cracks as the thing inflated. The artist stood by, drunk, in dungarees. "Stand back, baby!" he called to Joanna. "I don't know how big this thing is going to get!"

If only. There was nothing for her here.

Joanna wanted to sit down and relish her sorrow, but when she moved into the cool, damp rooms, there were shaky video installations occupying the spaces. The audiences squashed the unredeemed flesh of their backsides onto the benches: children bumbled in and out, avatar-blue in the flickering light. This is not art, thought Joanna. It reminded her of the station concourse, the grey and blocky lives of the commuters, everyone waiting for something else. Not Cape Town station but a Brueghel painting: not vice, just avarice. She found that somehow there was candyfloss matted into her hair and she batted at the sticky mulch, maddened, like a cat.

She pushed her way back out and chose a cobbled path that seemed less crowded. Through the clumps and strands of her ruined hair, she saw a clearing ahead, filled with a neat and gargantuan construction, a meeting of scaffolding and high wire. It was a perpetual motion engine, Joanna saw when she straightened up—or not that, but a performance, where the actors were acrobats. They were using their bodies to power the machine, their knees bicycling up and down, the parts whirring and clicking. They balanced, dived, returned.

Joanna leaned in to read the sign pegged on the machine: ODD ENJINEARS. She wished for the same merging of iron and flesh, like the little men her father had said lived inside wristwatches, turning the cogs. Here they were, come to life, with their bendy legs and bowler hats, each acrobat serenely partnered and rehearsed. They were slick with sweat: they had been going for hours, suspended, dependent, walking on air, and the end was nowhere in sight. The stragglers gathered around the performers clapped, chatty and jaded, blind to the effort that appears effortless.

Something nipped at her ankle, and Joanna pinwheeled, propped up only by the few people in front of her. They turned and smiled at her outfit and she wanted to smack them. I'm not asking you for forgiveness, you smug fucks!

She strained over their heads to see what had bumped her, and a furry little man with a wheelbarrow sped off. He was wearing earth-coloured lederhosen over gartered stockings. With one pistoning arm he pushed at the wheelbarrow and the tall thing in it. Why did men always do that for carnival—dress up in women's underwear? Was it meant to be funny? Secretly they hate us. She didn't enjoy wearing a bra, either, but somebody had to be in control; somebody had to say no. Otherwise, chaos.

She rubbed her grazed ankle, her backpack banging her ribs, and made a face at the small fuzzy man. He had already turned away, hunched over his barrow. Fucking pedal-pushers. And that selfish prick. He had delayed her evacuation plan. Now she would have to wait until she could put her weight properly on her foot again before she could go home. At least the trains were still running.

Joanna looked for somewhere quiet to sit, but she was distracted by the man with the wheelbarrow, who zigzagged back across her vision. He was so close she could smell the petrol in his ragged bush of hair. Then he was off, running in demented circles, drawing and redrawing private lines of desire like a spell in the sand. The sculpture he was pushing was a towering Babel of glue and paper, Joanna saw now, crisp as a clean serviette, begging for the lick of flame. It looked like a trellis of grotesque flowers, a zombie corsage, a ladder to God. There were other sculptures here and there over the Castle grounds, portable pyres of glue and wire and paper, in a pattern that could only be seen from the sky.

The capering man reminded her of someone. She marked his enormous bristling head, the narrow shoulders, his goatish legs stiff in their garters. His name would be Boris, she was sure, Boris or Viktor or Rumpel-fucking-stiltskin, a homunculus in tights. He looked like he fucked anything that moved. He held the barrow lopsided as a dance partner, pushing against it, the wheels fleeing him with agreeable squeals. It made her feel its weight dragging at her own wrists, the gravity of warm pipes and work well done. A hundred years ago this is what it must have been to handle a gun—some smooth tool that felt familiar in the hand, the way the right penis might. A tingling recognition began in her navel, like the singing of the grass, an earthy urge that made her want to grab the little man by the arms and shake agreement into him.

At last he seemed to make up his mind—here, no, here—according to some celestial mind-map. He set down the wheelbarrow, heaving, his hairy chest running with sweat. He looked around with the impudence of the well endowed, gauging his audience. Joanna gazed at him. This is your last chance, she told the universe. Make something happen. Make this worth my while.

The man scratched inside his lederhosen and produced a red lighter. Joanna knew by the sick tipping in her stomach what he was going to do. It was the same feeling she got when she saw the lawnmowers on the verges of the forest.

He bowed to her and held up the plastic lighter like Liberty. He flicked the ridged wheel and she felt its clitoral corrugations rub against her own thumb, the lemming lurch of destruction. Joanna moved closer, her ankle throbbing. She wanted to see it all, every detail of the roaring destruction after so much preparation. She wanted to grab his hairy-knuckled hand and shove it into her crotch.

The paper flowers went up fast: he'd designed it that way. He stepped back, unhurried, and the flames soared up into the sky and the full circus night. The smell of scorching forest came to her, as close as she was, and Joanna stopped herself from shielding her face. She felt the same vicious joy under her breastbone: to take and make and master—and to break, to crack and smother.

The man kept stepping backwards, prancing horsey steps, and turned to her, smiling and deliberate. The hair on his head didn't stop where it met his features, Joanna saw. It was just thinner in places, whorled like crop circles, then glossier and fuller at the sideburns. It grew down lazily over his neck, sprang from his nose and his ears, meandered gently over his chest and must have trailed down into the gusset of the garter belt. Promises, promises.

He peeled down the straps of his lederhosen, a blacksmith on a break. The leather flapped around his groin. He stroked the hair down on his stomach and then shook his hands, flicking sweat and smut from his fingertips onto her. Black magic, thought Joanna, and wiped her face. He nodded his odd-shaped head.

"Sjoe! I need a rest."

"You need a smack."

"What?"

"You hit me with your wheelbarrow."

He grinned, demonic. He reminded Joanna of Punch from the old puppet show, his face set in wicked rubbery lines that recessed his eyes so deeply she couldn't tell their colour. Around each socket were three precise wrinkles that fanned out whitely where the soot hadn't settled. He smelled like a wet dog.

"Sorry. You were camouflaged." He ducked his big head at her pedal-pushers. "Did it tickle when you painted them on?"

"At least I'm not in fishnets."

He really was incredibly hairy, a happy satyr. The thick fur on his thighs was compressed by the diamond weave of the tights: she wanted to stroke it like a Labrador.

She stuck out her hand instead. "Joanna."

He held out his filthy left hand in response, sinister, awkward. She saw that his right was withered and clawed.

"Hili."

His hand was hot. Well, of course it fucking is. He plays with fire!

"Is that Israeli?"

"No. Further, ah, south."

Joanna could smell his armpits, some sharp, bittersweet scent, and felt the synapses blistering in her brain, old pathways being cauterised, new ones being laid down. She wanted to grip his biceps and bury her nose in the clump of damp hair there. Her mouth was watering.

Hili glanced over at the wheelbarrow. It wasn't going to burn. Joanna could see his mental calculations, the coins dropping into worn slots. She shivered.

"Do you want to walk around?" he said.

"I'm just about to leave, actually." If my legs are still working.

"Why don't you stay? We can talk. I'm hungry, and my work here is done." He didn't say, "You look like a nice time."

"Okay. You can walk me to the gate." She fiddled in her tiny backpack. "I have a yoghurt…" Thanks, Siobhan. I'm glad we got something out of your eating disorder.

Joanna pulled the lips of the carton apart and squeezed an accommodating V for his slick mouth. She saw on the low ridge of his forehead that his eyebrows were singed.

"Oh, God. I'm sorry. It's sour."

Hili held onto her hand with his paw. "That's the way I like it." He drank in gulps, his Adam's apple shadowed by sworls of hair. Joanna thought of her father's friend, who had shaved his face and down his neck a little way and then given up, the clear and hateful boundary designating intention, like the poster of the neatly sectioned cow at Hough's Meats.

Hili, Joanna realised, liked his fur.

He crumpled the carton and tossed it. "Let's go."

She leaned on his arm, the hair squeaking under her fingers. She felt a pleasant relinquishing of control, a sleepy, tidal desire like the sea that used to lap in the Gat of the Castle, drenching the outlaws who knew to hold their breath, drowning the ones who screamed. Was it better to survive and suffer, or to surrender?

They walked out together through the Castle gates. She had suggested he leave her there but they kept going, under the moths' streetlights, under the rabbit's moon. By the time they reached the meadow, she thought, I was meant to come back here.

They walked into the honest grass and faced each other: Joanna was taller by a head. She shrugged out of the ridiculous backpack, and Hili put his arm behind her and tipped her over, a gentle version of the way the boys used to trip the girls at Kimberly Junior. On her back, it was all as she had imagined—a Café del Mar video, a song by Sting, the sweet grass closing over her head, like hiding in a laundry basket.

Hili stood up again, angled, architectural. His smell was very strong now: Joanna felt her nostrils flaring to take in more. And, because they had arrived, she knew what it was.

He was made of the grass itself, the seasonal uprising, the earth's dirty vegetable urge.

She tore off her shirt and lay back. He was busy disentangling himself from the lederhosen, a parachutist coming in to land. Joanna fingered the stiff hide where he let it fall next to her, the pucks and gathers warm from long settlement against the hinges of his body. What animal had once worn it?

"You can't wash leather," she said.

"No."

The stockings were next: how had he put them on with only one hand? Joanna saw that his dick had been shoved inside one of the stocking legs, to keep it down and out of the way. Did all men have penises this long? She struggled to sit up, feeling the stalks stuck in her hair like runners, as if she was growing into the ground, penetrating the earth in search of Persephone. I am about to be ploughed, she told herself. Ploughed and furrowed. The good earth. The fertile earth. The flaming trellis. Her teaspoon of bright blood would trickle out onto the soil here in the meadow and seed it for the next season. When she walked through it on her scissoring legs in September, she would know firsthand its heat and pain and growth.

Joanna unclipped his garters. The snick of their letting go was loud: there was pressure on her eardrums, the night air, the reversed juices of the grass like blood running the other way along their vessels, the ancient mammalian impulse.

His penis was the only part of him that wasn't covered in hair. It sprang up, freed from the stocking top and smelling of resurrection, eager and eternal and purplish-grey. Joanna reached out and touched the hard, shiny head at the end of the hose. The penis waved agreeably at her and produced one lubricating droplet, clear as venom. More, it said. Harder, and more. You know what to do.

She lowered her face to the fork of Hili's thighs, her lips already parted, and then she caught a flash of movement from the corner of her eye. Distracted, Joanna turned her cheek aside. His tortured hand again, the claw, flailing as if in a fit. He started making a sound, half hum, half growl, a wind-up monkey with sand in its works. It sent her back to a description she had read for an article on Van Hunks and Table Mountain. The entry was about the Devil—the Father, the witches called him. They said that Beelzebub's semen was ice. Would it feel like that with Hili—a snakebite searing and then numbness as the poison spread?

He pushed her back down, frowning, impatient. The rough ground under her shoulders made Joanna wriggle. The corners of the flat stones were digging into her, but she didn't want to move away. She put her hand on the pelt of his chest: it was hitching. She didn't mind the low moans, the soft panting-growling, or the flecks of spit. Hili kept licking his lips, his eyes so bright that they burned. What colour are they? Joanna's brain kept interrupting. Are they brown or blue or black?

From his stocking top Hili now pulled a small folding knife, the kind men got for Christmas but never used. "Leatherman," he said, and held it up in his left hand, steady even as the rest of him shook with excitement. He smiled and his teeth were yellow, with an old dog's striations.

She held the zip of her pedal-pushers away from her skin for him, and he flicked the blade under the cloth. He was going to divide her, known and unknown, cast off the bit of skin that stood between Joanna and experience. Hili yanked the blade through the fabric and her pants ripped and stuttered. Joanna pictured herself doing star jumps, bouncing high on the tiny trampoline of her virginity, a girl in a tampon advert, touching the sky.

And the pedal-pushers were gone: Joanna had shed her old skin. She stretched her grateful arms up over her head and closed her eyes: she was ready. Her back clicked back into place, her spine aligning with the stars, the music of the spheres rustling in concert with the grass as Hili lowered his hairy torso onto hers—and then she felt the rushing cold night air.

Joanna opened her eyes.

Where was he? Was this a joke? Oh, wilt thou leave me so unsatisfied?

"Hili?"

Silence. The grass, shifting. And there—the sound of someone running, breaking the stalks, and sobbing.

"Hili! Where are you going?"

And his voice came back to her, rough and despairing. "The bricks!"

Joanna angled her head and looked between her parted legs. She was lying across the old foundations of the vanished house, its long stone bones set into the surface of the earth.

She reached down with her fingers and felt along the scabbed and civilised threshold where no tokoloshe could enter. Then she lay back empty-handed, untouchable.