Andrea Hairston is the Artistic Director of Chrysalis Theatre and has created original productions with music, dance, and masks since 1978. Her plays have been produced at Yale Rep, Rites and Reason, the Kennedy Center, and on Public Radio and Television. She has received many playwriting and directing awards, including a NEA Grant to Playwrights, a Rockefeller/NEA Grant for New Works, and a Ford Foundation Grant to collaborate with Senegalese Master Drummer Massamba Diop. Since 1997, her plays produced by Chrysalis Theatre have been sf plays. "Archangels of Funk," a sf theatre jam, garnered her a Massachusetts Cultural Council Fellowship. Her play, "Thunderbird at the Next World Theatre," appears in Geek Theater—an anthology of science fiction and fantasy plays published by Underwords Press.

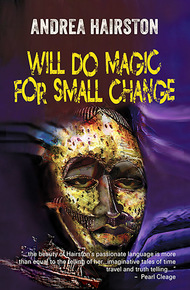

Ms. Hairston has published critical essays on Octavia Butler, speculative theatre and film, and popular culture. In 2011, she received the International Association of the Fantastic in the Arts Distinguished Scholarship Award for contributions to the scholarship and criticism of the fantastic. Lonely Stardust: Two Plays, a Speech, and Eight Essays was published by Aqueduct Press. "Griots of the Galaxy," a short story, appears in So Long Been Dreaming: Postcolonial Visions of the Future, edited by Nalo Hopkinson and Uppinder Mehan. A novelette, "Saltwater Railroad," was published by Lightspeed Magazine. "Dumb House," a short story appears in New Suns: Original Speculative Fiction by People of Color edited by Nisi Shaw. Ms. Hairston's novels include Will Do Magic for Small Change (2016 James Tiptree Jr. Award Honor List, 29th Annual Lambda Literary Award finalist, and 2017 Mythopoeic Awards finalist, and New York Times Editor's pick), Redwood and Wildfire (winner of the 2011 Tiptree Award and the Carl Brandon Kindred Award), and Mindscape (shortlisted for the Phillip K Dick and Tiptree Awards, and winner of the Carl Brandon Parallax Award). She is the Louise Wolff Kahn 1931 Professor of Theatre and Africana Studies at Smith College. Her next novel, Master of Poisons, will be published by Tor.com in September 2020.

Cinnamon Jones dreams of stepping on stage and acting her heart out like her famous grandparents, Redwood and Wildfire. But at 5'10'' and 180 pounds, she's theatrically challenged. Her family life is a tangle of mystery and deadly secrets, and nobody is telling Cinnamon the whole truth. Before her older brother died, he gave Cinnamon The Chronicles of the Great Wanderer, a tale of a Dahomean warrior woman and an alien from another dimension who perform in Paris and at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair. The Chronicles may be magic or alien science, but the story is definitely connected to Cinnamon's family secrets. When an act of violence wounds her family, Cinnamon and her theatre squad determine to solve the mysteries and bring her worlds together.

What can I say about the work of fabulous fantasist, the acclaimed author and playwright, Andrea Hairston? Here we have a magical mix of mythology, art, story telling, African and African American history, a circus, and a cast of queer characters. And really, what more can you ask? – Catherine Lundoff

"The entire work is filled with magic, celebrating West Africans, Native Americans, art, and love that transcends simple binary genders. Hairston's novel is a completely original and stunning work."

– Publishers Weekly, April 2016"At the core of Andrea Hairston's complex tale, Will Do Magic For Small Change, framed by Cinnamon's need to posthumously connect with her gay, dreamy, black-sheep brother, is the theme of journeying to the self. Cinnamon, as the child of a family scarred by race and class struggles, fights to carve an identity for herself out of the seemingly disparate elements of her life: femininity, art, blackness, geekdom, sexuality, spirituality. Paralleling this struggle is Kehinde, who was kidnapped from another people by the Fon and forced into the role of ahosi; she desperately seeks ways to prove that the Fon never truly enslaved her.... The only flaw in this beautifully multifaceted story is that Kehinde's tale outshines Cinnamon's, though this improves over time. Both stories are worth that time, however, with deep, layered, powerful characters. Highly recommended."

– The New York Times, N.K. Jemisin, April 24, 2016"Tiptree Award-winning author Hairston (Redwood and Wildfire; Mindscape) celebrates West African stories and traditions in this strange, ethereal coming-of-age fantasy that will attract readers of Nalo Hopkinson and Octavia Butler."

– Library Journal, June 15, 2016B O O K I

Pittsburgh, PA, December 1984 &

Dahomey, West Africa, 1892-1893

What is life? It is the flash of a firefly in the night. It is the breath of a buffalo in thewintertime. It is the little shadow whichruns across the grass and loses itselfin the sunset.

Blackfoot proverb

Public Display

"Books let dead people talk to us from the grave."

Cinnamon Jones spoke through gritted teeth, holding back tears. She gripped the leather-bound, special edition Chronicles her half-brother Sekou had given her before he died. It smelled of pepper and cilantro. Sekou could never get enough pepper.

With gray walls, slate green curtains, olive tight-napped carpets, and a faint tang of formaldehyde clinging to everything, Johnson's Funeral Home might as well have been a tomb. Mourners in black and navy blue stuffed their mouths with fried chicken or guzzled coffee laced with booze. Uncle Dicky had a flask and claimed he was lifting everybody's spirits. Nobody looked droopy — mostly good Christians arguing whether Sekou, after such a bad-boy life, would hit heaven or hell or decay in the casket.

"Why did Sekou give that to you?" Opal Jones, Cinnamon's mom, tugged at The Chronicles. "You're too young for —"

"How do you know? You haven't read it. Nobody's read it, except Sekou." Cinnamon wouldn't let go. She was a big girl, taller than her five-foot-four mother and thirty-five pounds heavier. Opal hadn't won a tug of war with her since she was eight. "I'm not a baby," Cinnamon muttered. "I'll be thirteen next August."

"What're you mumbling?" Opal was shivering.

"Books let dead people talk to us from the grave!" Cinnamon shouted.

Gasping, Opal let go, and Cinnamon tumbled into Mr. Johnson, the funeral director. The whole room was listening now. Opal grimaced. She hated public display. Mr. Johnson nodded. He was solemn and upright and smelled like air freshener. Opal had his deepest sympathy and a bill she couldn't pay. Dying was expensive.

"Why'd you bring that stupid book?" Opal whispered to Cinnamon, poker face in place.

"Sekou said I shouldn't let it out of my sight." Cinnamon pressed her cheek against the cover, catching a whiff of Sekou's after-gym sweat. "What if there was a fire at home?"

Opal snorted. "We could collect insurance."

"The Chronicles is, well, it's magic and, and really, truly powerful."

"Sekou picked that old thing up dumpster-diving in Shadyside." Opal shook her head. "Dragging trash around with you everywhere won't turn it into magic."

Cinnamon was losing the battle with tears. "Why not?"

Opal's voice snagged on words that wouldn't come. She made an I-can't-take-any-more gesture and wavered against the flower fortress around Sekou's open casket. Her dark skin had a chalky overlay. The one black dress to her name had turned ash gray in the wash but hadn't shrunk to fit her wasted form. She was as flimsy as a ghost and as bitter as an overdose. Sekou looked more alive than Opal, a half-smile stuck on the face nestled in blue satin. Cinnamon inched away from them both.

Funerals were stupid. This ghoul statue wasn't really Sekou, just dead dust in a rented pinstripe suit made up to look like him. Sekou was long gone. Somewhere Cinnamon couldn't go — not yet. How would she make it without him? Pittsburgh's a dump, Sis. First chance I get, I'm outa here. Sekou said that every other day. How could he abandon her? Cinnamon brushed away an acid tear and bumped into mourners.

"God's always busy punishing the wicked," Cousin Carol declared. She was a holy roller. "The Lord don't take a holiday."

Uncle Dicky, a Jehovah's Witness, agreed with her for once. "Indeed He don't."

"So Hell must have your name and number, Richard, over and over again," Aunt Becca, Opal's youngest sister, said. "This chicken is dry." A hollow tube in a sleek black sheath, she munched it anyway, with a blob of potato salad. Aunt Becca got away with everything. Naturally straight tresses, Ethiopian sculptured features, and dark skin immune to the ravages of time, she never took Jesus as her personal savior and nobody made a big stink. Not like when Opal left Sekou's dad for Raven Cooper, a pagan hoodoo man seventeen years her senior. The good Christians never forgave Opal, not even after Cinnamon's dad was shot in the head helping out a couple getting mugged. Raven Cooper was in a coma now and might as well be dead. That was supposedly God punishing the wicked too. Cousin Carol had to be lying. What god would curse a hero who'd risked his life for strangers with a living death? Cinnamon squeezed Sekou's book tighter against her chest. God didn't take a holiday from good sense, did he?

None of Opal's family loved Sekou the way Cinnamon did. Nobody liked Opal much either, except Aunt Becca. The other uncles, aunts, and cousins came to the memorial to let Opal know what a crappy mom she was and to impress Uncle Clarence, Opal's rich lawyer brother. An atheist passing for Methodist, Clarence was above everything except the law. Sekou's druggy crew wasn't welcome since they were faggots and losers. Opal didn't have any friends; Cinnamon neither. Boring family was it.

"I hate these dreary wake things." Funerals put even Aunt Becca in a bad mood. She and her boyfriend steered clear of Sekou's remains.

"The ham's good," the boyfriend said. He was a fancy man, styling a black velvet cowboy shirt and black boots with two-inch heels. Silver lightning bolts shot up the shaft of one boot and down one side of the velvet shirt. His big roughrider's hat with its feathers and bolts edged the other head gear off the wardrobe rack. "Why not have supper at home, 'stead of here with the body?" He helped himself to a mountain of mashed sweet potatoes.

"Beats me." Aunt Becca sighed.

Opal couldn't stand having anybody over to their place. It was a dump. What if there was weeping and wailing and public display? Aunt Becca glanced at Cinnamon, who kept her mouth shut. She didn't have to tell everything she knew.

"Some memorial service. Nobody saying anything." Becca surveyed the silent folks clumped around the food. "Mayonnaise is going bad," she shouted at Opal over the empty chairs lined up in front of the casket. "Sitting out too long."

"Then don't eat it, Rebecca." Opal sounded like a scratchy ole LP. "Hell, I didn't make it." She needed a cigarette.

"Sorry." Becca pressed bright red fingernails against plum colored lips. "You know my mouth runs like a leaky faucet."

Uncle Clarence fumed by the punch bowl. His pencil mustache and dimpled chin looked too much like Sekou's. "Opal couldn't see the boy through to his eighteenth year. I —"

Clarence's third wife read Cinnamon's poem out loud and drowned him out:

Sekou Wannamaker

Nineteen sixty-six to nineteen eighty-four

What's the word, Thunderbird, come streaking in that door

A beautiful light, going out of sight

Thunderbird, chasing the end of night

Cinnamon joined for the final line:

What's the word, Thunderbird, gone a shadow out that door

"Hush." Opal turned her back on everyone. Maybe it was a stupid poem. "Sekou talked a lot of trash. You hear me?" She touched the stand-in's marble skin and stroked soft dreadlocks. "When he was high, he didn't know what he was saying — making shit up. Don't go quoting him."

Cinnamon chomped her bruised lower lip. "The Chronicles is a special book, magic, a book to see a person through tough times." She threw open the cover. Every time before, fuzzy letters danced across the page and illustrations blurred in and out of focus. Of course if you couldn't stop crying, reading was too hard. This time the pages were clear. The letters even seemed to glow. She dove right in.

Dedication to The Chronicles

The abyss beckons.

You who read are Guardians. For your generosity, for the risks you take to hold me to life, I offer thanks and blessings. Words are powerful medicine — a shield against further disaster. I should have written sooner. Writing might help me become whole again. I can't recall most of the twentieth century. As for the nineteenth, I don't know what really happened or what I wished happened or what I remember again and again as if it had happened. I write first of origins, for as the people say:

Cut your chains and you become free; cut your roots and you die.