Steven-Elliot Altman is a bestselling author, graphic novelist, ADDY Award-winning advertising executive, television writer-producer, and most recently a successful videogame developer, having served as the Games Director at Acclaim Games, and having won multiple awards for the games he has penned which include such titles as: 9Dragons, which boasts 15 million registered players; Pearl's Peril, which boasts 90 million players; Ancient Aliens: The Game and Project Blue Book: The Game which Steve wrote, produced and narrative designed for The History Channel, based on two of their hit television series, and his latest game is Terminator: Dark Fate, based on the feature film.

Steve's novels include Captain America Is Dead, Zen in the Art of Slaying Vampires, Batman: Fear Itself, The Killswitch Review, The Irregulars and Deprivers. He's also the editor of the critically-acclaimed anthology The Touch, and a contributor to Shadows Over Baker Street, a Hugo Award Winning anthology of Sherlock Holmes Stories. Steve's also a proud member of the Horror Writers Association, the Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America, the Canadian Writer's Guild and the current Vice-Chairman of the steering committee of the Writers Guild of America's Videogame Division.

Steve has done panels on writing books and games at the comic conventions every year since 2000; from San Diego Comic-Con, WonderCon, BayCon, Dragon Con, Westercon, and Salt Lake Comic Con on the literary front; to E3, Slush (Finland), Pocket Gamer Connects (UK), Columbia 3.0 (Columbia), Gamescom (Germany), and GDC San Francisco on the gaming front. He has served as a Finalist Judge for the WGA Videogame Awards since 2009, and more recently as a Finalist Judge for the CDC's Game On Challenge.

When Steve's not writing he is often playing social games with strange and wondrous people on and off of airplanes between Florida, New York and Berlin.

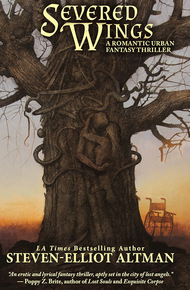

From the bestselling author of Deprivers, Steven-Elliot Altman's Severed Wings is a romantic, urban fantasy thriller. A haunting take on the mythos of angels living among us. Fans of American Gods to Twilight will devour it. Steve also wrote the popular videogames 9Dragons, Pearl's Peril, Ancient Aliens, Project Blue Book and Terminator: Dark Fate.

"This dark, alluring story will appeal to urban fantasy fans."

– Publishers Weekly"An erotic and lyrical fantasy thriller, aptly set in the city of lost angels."

– Poppy Z. Brite, author of Lost Souls and Exquisite Corpse"Steve Altman's Severed Wings is a tour de force of the Weird. Eat of the fruit and take a truly mesmerizing trip through a glass darkly. I did, and I can't wait to do it again."

– Nancy Holder, New York Times Bestselling Author of the Wicked series, written with Debbie ViguieI woke up to the harsh light of a hospital room and the sound of crying. My mother sat hunched over beside my bed clutching rosary beads. She looked haggard, her clothes unpressed as if she'd slept in them.

"Mom…" My voice cracked. I could barely form the sound.

She gasped and leapt up, reaching for me, but there was nowhere to put her hands. My arms and legs were held aloft by a three-dimensional maze of wires, tubes, and hangers.

"You've been in a very bad car accident," she whispered. "God saved you. Father Tom has been in to see you and says it's a miracle you survived."

She probably would have gone on in that vein if the doctors hadn't come in. They told me I'd suffered acute fractures to the lower thoracic and upper lumbar regions of my spinal cord. Neural trauma. I couldn't quite follow it all through the haze of morphine—a grogginess that made me feel detached from reality, from the room, from the tubes and wires and beeping monitors, from whatever it was they were trying to explain to me.

Slowly, I came to understand—seeing their faces, letting their words sink in—the full impact of what they were telling me. They had to tell me several times, and even demonstrate, before I understood completely that I could not feel or move my legs.

I'd been in a head-on collision on the 405 freeway that had severed my spine in one horrific crush of glass and steel, leaving me paralyzed from the waist down. My only consolation was that the drunken frat boy who'd crashed into me was no longer with us.

Felicia camped out by my bedside throughout my hospital stay, tolerating my misplaced rage as day after day, somber specialists came back with the same bleak prognosis. "Medical science keeps advancing. There is a chance you will walk again someday, son. Hang in there, Brandon."

Six months later my condition had not improved, despite endless hours of physical therapy and my mother's unceasing prayers. I was living with my parents again; a helpless cripple dependent on their charity, convinced that my whole life lay behind me, wishing I were dead.

I'd sit in my wheelchair, which I'd christened the "cripple wagon," and stare in the full-length mirror on the back of my bedroom door—the only mirror in the house low enough for me to see myself. My useless legs remained senseless against the steel leg supports, my feet dead weights on the footrests. My hands, half covered by leather gloves that left my fingers bare, clutched the metal rims of the rubber wheels. My arms by now had grown twice as muscular as they'd been before the accident. The result of all the physical therapy, and my refusal to let anyone help me with the chair.

Ironically, after all I'd been through my face still matched my headshots. My agent sent me out on two auditions. Although the studios are legally supposed to be blind to handicaps, it was clear to me that both casting directors took one look at my wheelchair and decided that I "wasn't right" for the parts before I even read my lines.

I was so upset after the second failure that I called the Screen Actors Guild to report discrimination. The woman I spoke to told me I could file a complaint, and if I proved it the casting people would be fined. Then she explained what would probably happen. I might be offered a single episode walk-on part—no pun intended—to shut me up. More likely, I'd be quietly blacklisted, allowed to audition but never hired. Seeing my true calling slipping beyond my grasp forever somehow felt worse than being sentenced to life in a wheelchair. Faced with the harsh reality of my situation, I told her to forget it.

As I was about to hang up, she asked, "But you are taking advantage of your disability benefits, right?" She told me she knew of a reasonably priced apartment in West Hollywood for which I qualified.

That was the day I decided I'd had enough humiliation. It was time to make some changes.

*

The Villa Rosa is a four-story white stone apartment building between Fairfax and Orange Grove Avenue on Sunset Boulevard. With its prominent black fire escapes, it looks like it belongs on some side street in Brooklyn rather than on the main drag in Los Angeles. Hearing that I was an actor, the pudgy, sweat-stained rental agent who showed me the place enthused that it had housed a lot of aspiring talents who went on to have highly successful, often tragic careers, chief among them James Dean.

I belong here, I thought.

She fumbled out two sets of keys from her purse at the arched black iron security gate.

"The buzzer links to your phone," she said, indicating the tenant directory as she wiped sweat off her forehead. This was common now for LA apartment buildings, replacing the old intercom system; you'd answer your phone instead, then press 9 to buzz someone in. "Otherwise, it's remained pretty much the same as when it was built as a hotel back in 1928," she added. "It's sort of like going back in time."

She held open the gate, and I wheeled my cripple wagon past her into a sunny courtyard on either side of which rose the two wings of the U-shaped building. Like an eager tour guide, she proceeded to describe in detail what made the Villa Rosa "special" while we moved along a path of paving stones bordered by palm trees stretching all the way up the sides of the building and crowning the rooftops with their luxuriant fronds.

"Those trees were planted by one of the tenants a long time ago," the agent said. "Can you believe it?"

The path widened at the end around a sculpted bronze fountain centered within an octagonal pool faced with Spanish tiles. Koi swam in the water. A few feet beyond the fountain was the entrance to the lobby, whose antique wood doors, the agent told me, were always left open.

The lobby had a row of metal mailboxes on our right and a long, rudimentary wood bench on the left, low against the wall. The floor was terra-cotta tiling. Dominating the lobby was a colorful floor-to-ceiling stained-glass window facing outward to the courtyard. It depicted a wooden ship with full-blown, broad-striped sails at sea with the words Villa Rosa in red block letters emblazoned beneath it. A circular wrought iron chandelier with eleven miniature shades hung from the ceiling.

Off the lobby was the ancient wood-paneled elevator, which fortunately accommodated my wide wheels. The agent mentioned that there was a laundry room in the basement. We ascended to the fourth floor.

"There are actually two apartments vacant on this floor," she said as we turned a corner to our right after exiting the elevator. "But only one of them is designated… handicap accessible."

I followed her along a dimly lit hallway at the far end of which French doors had been left open, revealing the black metal fire escape. Shafts of sun, like light at the end of a tunnel, reflected softly on the rustic plaster walls. Exposed black iron piping spanned the ceiling from one end to the other. A well-worn carpet runner with a leaf-and-flower pattern stretched the length of hallway, with heavily varnished plank hardwood flooring exposed along the edges. The agent pointed out the narrow black metal plates bolted to the floor at irregular intervals, explaining that they were earthquake support braces, installed just after the 1994 Northridge quake.

The apartment was a large studio with exposed brick walls and, once again, plank hardwood floors with seemingly haphazardly placed earthquake braces. The small caster wheels of my cripple wagon bumped as I rolled over them.

"Check out the view," the agent suggested.

Through three tall windows facing Sunset Boulevard, I could see the Hollywood Hills to the northeast, with Griffith Observatory in the distance looking like a small Parthenon atop Mt. Olympus. A corner window overlooked Orange Grove Avenue, with downtown Los Angeles sprawling to the southeast. All of the windows had wrought iron security grilles with heart-shaped motifs.

The agent directed my attention back to the apartment's interior. "You're gonna love this," she promised. She led me across the living room to what appeared to be a polished wooden armoire, recessed into the wall—then reached to unlatch it—and demonstrated that is was in fact a hidden, queen-size Murphy bed, which lowered effortlessly into place.

"Fun, right? Most of the studios have them," she said. "Murphy beds were commonplace back in the day. They allow for more functional living space."

A kitchen area was separated somewhat from the main room by a counter, with cabinets and refrigerator shelves all low enough for me to reach from my wheelchair. The shower and toilet in the bathroom, down a short hallway, were also cripple friendly. The place came furnished. All the furniture was custom-made, left behind by the previous tenant, who had also been wheelchair bound, and had died there.

I knew this because I discovered an embossed prayer card from his memorial service peeking out from beneath some dusty papers which had been left sitting atop the overfilled trash bin.

Died peacefully in his sleep at his apartment on…

My breath caught as I read the date of death.

I had to read it again to make sure my mind wasn't playing tricks on me. I was aware that the agent continued to speak, but her voice grew suddenly distant and unintelligible as my realization solidified.

He'd died on the night of my accident.

Chills ran through me and left tingling gooseflesh up and down my arms. What were the chances of that?

I turned the card over to reveal a familiar painting of a haloed angel, head bowed, wings extended, hands steepled in prayer.

This must be where I'm supposed to die, too, I thought. A fitting tomb for a willing occupant.

I realized the agent was hovering over me, her face a mask of concern. "Forgive me, did I forget to mention the last tenant passed away here? To be honest, he wasn't the first. John Drew Barrymore passed on here as well. He was an actor turned acting coach who operated out of the building. Coached James Dean and Steve McQueen right here in the apartment. Word has it he struggled with drugs and alcohol his entire career."

Now, my relationship with God had grown complicated since the accident, to say the least. But these were signs that were impossible for me to ignore.

"I'll take it," I told her.

*

About a week later, the strategic withdrawal from my prior life was nearly complete. My parents hired movers to transport my belongings and stocked the fridge. I had cable, Internet, Netflix, and menus from every eatery that delivered food to the area. A maid was scheduled to arrive once per week. Through the pity of several government agencies and my labor union, just enough money filled my bank account each month to cover my few expenses. The next order of business, before I could get down to proper grieving for my shattered existence, was breaking up with Felicia.

Before the accident, we'd planned to move in together, get married, and eventually have kids, meanwhile reaching the height of our careers and stowing away tons of cash. None of that was going to happen now, at least not in my case, yet still Felicia stuck by me.

After the hospital, she'd spent every other night with me at my parents' house. She had a life of her own of course—friends to visit, a dog to walk, auditions to attend. I understood. At first we kept up hope that the doctors were wrong, that my spinal injury would not permanently inhibit my ability to perform in bed. Lack of ability did not mean lack of desire. If anything, I was hungrier for her now than I had been before the accident. Like a phantom limb, my erection made itself known every time Felicia and I got close. But paralyzed from the waist down means exactly that. Despite my brain's insistence that I was ready to go, my body was not on the same page, or even in the same book.

The first time we made the attempt, we were naked together, kissing. I could feel myself hard and ready for her. For a few seconds, I exulted in the miracle I'd been given. I looked down at my flaccid, useless flesh. That may have been the most unbearable moment of my life.

After that, we'd tried everything from pornography to Viagra to a particularly mortifying attempt with a vacuum pump. Each failure introduced me to new depths of despair. But my fingers still worked, and so did my mouth; despite my poorly hidden frustration, I mastered both techniques to a degree I never would have otherwise. It worked for a time. Felicia's compassion and patience seemed endless. "I don't need all that other stuff," she said, and we both needed to believe it.

But soon after I'd moved into the Villa Rosa, I'd built up the courage to face the truth and cast off the emotional cushion she provided. My girlfriend had the yearnings of a fit young woman in her prime. I had those yearnings, too, and had been cursed with an injury that rendered my body unable to service either of our considerable drives any longer. We'd lie in bed, naked, engaging in the poor imitation of the love we'd once made so enthusiastically. I'd see the wanton look in her eyes I knew well, and I just couldn't take it.

And I'll admit I was guilty of checking her text messages and knew she was resisting the attentions of a guy she'd been partnered with for scene study in her acting class. I'd met him once or twice before the accident, and it made me jealous as hell for a while. Felicia was a good girl. I imagined her fending him off, out of pity and loyalty to me. "I'm not ready yet. It's too soon. He's crippled. Be patient, it's not like we're still having sex." That was no way for her to live.

So, as the last act of control I could muster over my past, I picked a fight and ended our relationship before her hormones inevitably did.

I accused her of sleeping with her manager. She vehemently denied it.

"If you're not sleeping with him, you'll be sleeping with someone else sooner or later," I countered. "I know what you like, Felicia. I can't provide it anymore, and what we are doing certainly doesn't satisfy me."

The fight escalated. Foul words were spoken and we both shed many tears. In the end, we assured each other we'd be friends again eventually, and Felicia gathered up the few belongings she kept at my apartment—a toothbrush, a hair dryer, a coat from the closet—and walked out the door without looking back. I wheeled myself to the fire escape to watch her get into her car and drive off for the last time, then rolled back into the apartment feeling empty, yet relieved.

I'd like to say the breakup was altruistic on my part, that I couldn't bear to keep denying my girlfriend a normal sex life. The truth is, Felicia had become for me a mirror of what my life once had been. Staying with her was a constant, painful reminder of my emasculation. I couldn't handle it. And I couldn't stomach the thought of her being with anyone else. My vanity and ego wouldn't stand for it. I've admitted this to myself. In my defense, I told myself I didn't want my handicap to extend to her, that our relationship was destroyed by tragic circumstances and she was better off without me. I prayed she'd find someone who would treat her as she deserved.

Our two headshots had been mounted in frames on the living room wall. I left hers up for several days, then finally had to take it down because it was too painful to look at. Ironically, as I wriggled the nail out to remove her headshot, mine slipped off the wall and hit the floor, shattering the glass. I cleaned up the shards, trashed both pictures, spackled the nail holes, and refreshed the paint.

Next I went about exorcising friends from my life. For a few, it was as simple as not returning their calls or failing to answer emails. Others required blocking or deleting from Facebook. Losing the more persistent ones took work. Finally, I changed my cell phone number and deleted all my social media accounts. I assume word got around that I wanted to be left alone.

The last of them was Marty, my best friend since junior high school. He persuaded my folks to give him my address. (Who could blame them? I had not taken their calls in weeks.) I had no choice but to buzz him in when I answered my phone and discovered he was downstairs at the Villa Rosa gate. He was clearly surprised when I opened my apartment door.

"Jesus, when was the last time you shaved, Brandon?" he said. "You look like hell."

"It's good to see you, too," I lied.

I'd dimmed the lights in my studio while he was on his way up, and drawn all the curtains. Now I wheeled myself to the cabinet to get a pair of clean glasses, uncorked a bottle of wine for us to share, put on a CD of Tibetan monks chanting, and lit a candle for dramatic effect, setting the stage for the murder of our friendship.

"Who else knows you're here?" I began. "Please tell me you haven't given my address out to the old crew."

"Of course not," Marty said. "But people are worried about you. Including your folks."

"Why are they worried?" I asked, sipping my wine. "Do they think I can't take care of myself because I'm alone and crippled?"

I could tell Marty was nervous. The stem of his wineglass trembled in his hand; I noticed perspiration on his upper lip.

"No, no," he stammered. "People still love you, man. We can't understand why you don't want to see us."

I detested myself for what I was about to do as I called on my acting skills and allowed just a trace of disgust to appear on my face, careful not to let the demon out too fast. Poor Marty was merely an innocent audience member to my self-destruction.

"You don't understand," I echoed him savagely. "You can't fathom why I'd want to detach myself from everything that reminds me of who I used to be? I see you, and I remember running across the field during lacrosse practice. I see Sarah, and I remember rock climbing in Yosemite. I can't walk or run or climb or drive anymore. I can't act, or have a normal relationship. Forget about having children—I can't screw!" I was shouting now. "I'm done, Marty. And I don't need you coming here to remind me. So take your pity and fuck off!"

I was good—as good as if I'd rehearsed this unpleasant little scene.

"Brandon, I…" He was unable to continue. Tears welled in his eyes. He took a few halfhearted sips of his wine. He stared at the floor.

We sat in silence for about a minute. Finally, he got up, his chair making an unnerving screech as he pushed it back, and showed himself out.

I locked the door behind him, wondering if I'd made a mistake. Marty was my best friend. But it was better this way. My past was dead. From now on, there would be no more painful reminders of who I'd been or my promising future, no one to compare me to my former virile self. From now on, I would only let new people into my world, people who'd never known me as anything other than a cripple.

I finished the bottle of wine while I watched that old Stephen King movie where the guy's car is possessed by a demon.