Marie Whittaker is an award-winning essayist and author of urban fantasy, children's books and supernatural thrillers. Marie has enjoyed professions as a truck driver, bar tender, and raft guide and is now associate publisher at WordFire Press.

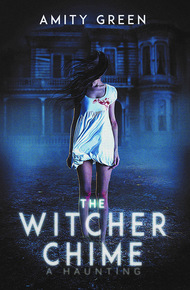

Writing as Amity Green, her debut novel, Scales, the first in her Fate and Fire series, debuted in 2013, followed by Phantom Limb Itch in 2018. Her supernatural thriller, The Witcher Chime, was a finalist for the Indie Book Awards in 2017. Many of her award-winning short stories appear in numerous anthologies and publications. A Colorado native, Marie resides in Manitou Springs, where she writes and enjoys renovating her historical Victorian home. Marie is a proud member of the Horror Writers Association and keeps steady attendance at local writer's groups. She spends time hiking, gardening, and indulging in her guilty pleasure of shopping for handbags. She is fond of owls, coffee, and all things Celtic. A lover of animals, Marie is an advocate against animal abuse and assists with lost pets in her community. Visit her at www.amitygreen.ink.

A deadly, possessive entity imprints on members of Savannah Caleman's family, making her the latest object of obsession in this chilling, historical tale of haunted legacy and terror.

In 1922 and in 1988 a deadly, possessive entity imprints on members of the same family, ancient as Genesis and determined to remain free. Savannah Caleman is the latest object of obsession in this chilling, historical tale of haunted legacy and terror. Savannah Caleman's family has been coming apart since the early 1920's.The evil plaguing her family dons a suit and tie and introduces himself, giving Savannah an ultimatum. She must decide between her sister's safety and aiding a monster that can't be identified as either an angel or a demon. Either way, Savannah is torn, and takes to single-handedly running the family affairs with precision as she takes care of her sister. The Witcher Place is transformed to her liking using family money. Distractions are only that. Releasing a monster to roam at will isn't a stellar option, no matter the promises it makes. The stain of murder and torment cannot be erased. He has fallen, been shackled, and now has plans to rise once more using Savannah as the key to regain grace.

"Amity Green's novels will hold you spellbound from the first page to the last. Wise and witty, Amity proves she is a talent to watch!"

– David Farland, New York Times Bestselling Author"I'm a hard sell when it comes to chills. I write scary stuff for a living and, let's face it, we live in scary times, but THE WITCHER CHIME raised some goosebumps. Mainly because Marie Whittaker (writing as Amity Green) knows how to craft characters you care about. And if you become emotionally connected to the characters, you feel their feelings and share their sense of threat. Overall...a fine read for a creepy night!"

– Jonathan Maberry -NY Times Bestseller"That the sons of God saw the daughters of men that they were fair; and they took them wives of all which they chose."

Genesis 6:2

The Witcher Place, Victor, Colorado

June 6, 1988, 7 p.m.

Savannah Caleman stepped onto the porch planks, dropping a round gas can beside the door with a derisive, metallic clank. Everything she touched was coated, fuming, and combustible. Muted sunlight tumbled through foggy dusk. A warm, afternoon wind blasted last winter's leaves from the aspen grove across the yard, scattering streaks of burnished gold in contrast to a bruised sky. The wind chimes danced with uneven low harmony, claiming the peace. The screen door smacked shut, bounced from the jamb and came to a whining stop. Cool chain links grated in her clammy grip as she sat on the porch swing for the last time and started a gentle pace in an easy to-and-fro. Darkness poured from inside the house, the divided-light panes contrasting Mother's sun-yellowed sheers pulled back at the sides. The entire thing was tinder.

A reluctant, sad smile tugged at Savannah's dimples. Soon, the whole damned house would burn, the ashes a tribute to the ruin of her life, carried away by black smoke spiraling into the night sky. The minutes ticked by with the creaking of the swing as she fought the urge to get it over with, to strike a spark of life into looming death. Timing was everything. Oblivion was her reward for waiting it out.

A mountain lion screamed in the distance. Finally. Savannah pulled a crushed box of matches from a dampened pocket, fingering the strike pad as the wind quieted. The family's horses trotted through the yard, experimenting with freedom. A fresh sob caught in her throat when her mare stopped at the porch steps and nickered to her. Savannah closed her eyes, tears cascading. So much hate fractured her heart. The bastard that drove her to such an extreme belonged in hell and after what he'd done to her family, it was her pleasure to escort him through the flaming gates.

"Go! Yah!" she yelled, flipping an arm. The horses snorted and took off at a sprint toward the hay field.

The chimes slowed as the wind calmed and eerie silence took over. She didn't react, just waited it out, watching her fuel-splattered cowboy boots swing above the painted porch floor. Tears dried, salty in the corners of her mouth. Strands of hair stuck to her cheek, but she left it that way. She'd assigned her lot. She was simply bait. A worm on a hook. A snared rabbit with a predator following her screams.

The heavy scent of decay bounded from the trees, tumbling toward her on an invisible fog. For the first time she wasn't terrified when the death-scent thickened until it was the only tint on the air. Nausea rumbled in her gut and she swallowed hard.

Mother had left three sleeping pills in the medicine cabinet and Savannah had taken them to mute the sting. They'd done a little more than that, and she was dizzy as hell, but the time had come. She wiped her face on her shirt and slid from the swing, pulling the screen door wide enough to touch the side of the house as she hurried through to the stairs. Aged wood creaked beneath footsteps behind her, and to no surprise, the screen didn't slam, instead being caught and held open.

A fist of adrenaline clenched inside her chest as she fought the urge to sprint up the stairs on wobbly legs. One careful step leading another, Savannah ascended to her bedroom through a growing haze, closed the door, and dropped onto her bed. Wet linen clung to her t-shirt and skin as she backed against the headboard, feeling tendrils of her long hair clinging to accelerant dripping from splashes on the wall.

A small line of saliva plummeted from her bottom lip, chilling her chin. She wiped it away with a wrist, amazed at just how screwed up she was after taking a few little pills. An empty stomach likely amplified the drug, which battled adrenaline in her system. The jarring thrash of beats against her sternum faltered, and she hoped her heart would soon give in to sedation. Tears mixed with cold sweat as she forced herself to concentrate on good thoughts and wait for the right second. She couldn't jump the gun and spring the trap too early.

Savannah closed her eyes and focused on memories of her siblings. Chaz and Molly danced with her in the kitchen, red balloons tethered to their little wrists with strings, bouncing in rhythm as they giggled, singing along with "Monster Mash." A weight anchored around her ribcage, pulling her against the mattress with soothing, cool waves of calm.

When the doorknob wiggled once and began to twist, she readied a match against the pad on the carton, grasping hard to avoid dropping it with her sloppy grip. The door swung, wedging slowly to reveal a rectangle of darkness.

"Here kitty, kitty," she crooned.

***

Chapter 1

The Cresson Mine, Cripple Creek, Colorado

June, 1922

"The bloody thing's lost its wits."

Four men huddled beneath a pitiful light bulb, encircling a brass birdcage, watching a canary flit about. Feathers puffed from within the small area, knocked free when the bird launched itself one last time against the bars. One wing continued to pump at the cage floor, where the small bird landed, tiny head cocked at an impossible angle and chest heaving.

The wings stopped and the miner holding the cage at eye level deposited the untimely little tomb onto the uneven, cut-rock floor. The men continued to stare, wide-eyed and gathering closer in the meager halo. Machinery chugged softly from far above, steel wheels screeching along tracks.

"The air's tainted, then," a miner stated with a tremble that rivaled any common stutter.

"They don't do that. They just kick over. And this'uns still breathin'," another said. "It ain't the gas."

"What the hell's wrong with it, then?" the man asked, nudging the cage a bit with the toe of a boot. "'Suppose it don't matter no way. We get topside or we're dead men."

The smallest of the men crept to the farthest reach of the light, wet eyes even wider than his normal, scattered look. "Somethin's wrong in here," he said with a quaky voice. "Animals sense things us men can't see."

"Spare us, Nelson. We don't need none of your woo-woo shit down here," one gruff voice warned.

Nelson shook his head, pointing a shaky finger at the cage. "If that bird's tryin' that hard to get outta here, we should be, too."

"One went out on us at the Independence last year, before those poor bastards rode the cage to the bottom," the first said, approaching for a better look. "Faint-hearted, these little ones."

No one spoke as fresh memories circulated. Vignettes of terror played as each man's mind recapped a version of the accident. Fifteen miners were literally broken to bits when the cable frayed loose, sending the lift plummeting over fourteen-hundred feet to a miner's version of a sump-soaked hell.

"Poor bastards," he said, again his low voice breaking dense silence. His breath laced into steam in the dim paths of light. They took turns huffing clouds of vapor in disbelief.

"That's a day, then." Nelson paced free of the group, snatching gear and tossing it onto a half-full ore cart. "The damned bird's given up the ghost and the temp dropped somethin' mighty."

"It's no' upta you. What ya reckon, Charlie?" one man asked, gesturing to the crew foreman with a nod.

Charlie Caleman, a shifter who'd built years of confidence as a lead, didn't make snap decisions. He nodded calmly. The big man stood half a foot over the tallest, searching the faces of his crew and returned his gaze to the first one who'd spoken up— his brother, Paul. He considered quickly. Three lives depended on his judgment. The first instinct was to keep the calm and get them out. They were low, nearly seven hundred feet deep at the bottom of the shaft and had made decent ground that day, cutting a new room into the mountain. The ceiling was right at seven feet, and they'd hollowed out enough flat ground that the men walked easily from cart to shaft under a new line of electric light. Going got real rough for the last hour and some, but fluorite and dusty quartz ran thick in purple veins, pointing to pay dirt that would still be there at the top of a new day. He gestured toward the path out.

Nerves spiked in his stomach. A bird kickin'off was one thing. The life of a miner was another. He tilted his timepiece to the light, steeling himself. There was less than an hour left before he and his men would head topside for the night anyway. He clasped the watch closed, sending a metallic snap ricocheting from wall to wall in the chiseled-out cave.

"Pack it in," he said, low and calm. "Get yourselves out. Nelson," he said, holding the flighty miner's gaze, "calm the hell down so you don't get one of us hurt."

No one argued against their shifter, or superstition, both of which were known to keep miners alive. The men hastily turned to retrieve various diggers and canteens.

Nelson jerked his pick free from where he'd lodged it into the rock wall. The crackle of splitting granite rent the dim room. The men stopped their hustle for an instant when the light flickered. Air hissed somewhere, filling the space with the smell of a hundred corpses. A lone splinter of stone slashed free, tumbling and clacking from above, coming to rest inside their meager line of light.

"Aw Jesus!" Nelson screamed, breaking into a flailing sprint for his life.

"She's comin' down—" one crew-member yelled, the last of his words cut off when a slab of rock slammed down from above. His helmet shot against a wall as bone crushed with wet snaps, and frothy gurgles of air released from organs. The mountain screamed as gasses pushed free, busting cracks in every direction. Fissures slashed through stone fast as lightning cutting the night sky.

Charlie Caleman didn't know why, but he dodged a blast of gravel, grabbed the bird cage and lunged toward the stope leading to safety as a wall of fluorite-veined granite sloughed, crushing his crew and brother behind him so fast he only heard one tortured scream from inside.

* * *

Three months after the death of her husband Paul, Rebecca Caleman refused to wait for the bank to claim her house in Victor, Colorado. She let defeat slide off her shoulders and silently released the property in hopes of retaining the last shreds of her dignity. In the days shortly after the mining accident that claimed her husband, the cellar stocks ran empty so she picked up and moved her four daughters and one son a few miles south to the Caleman family ranch on the Shelf Road. Her husband had worked hard to afford a nice home for them, away from the drudgery of ranch life. Rebecca was grateful her in-laws maintained the Caleman property and offered them a portion of the monstrous house.

Paul had been a good husband, and his brother Charlie remained one of the most kind-hearted. Although he was a gruff shift boss at the mine, losing his brother just weeks before had taken a toll on Charlie, leaving his face creased with grief and diminishing his easy smile. Rebecca cycled, trying to hate Charlie for being the one that survived. Certainly, it was chaos in that shaft when the mountain came down, but wasn't there one thing he could have done to save his brother? Why save a dead bird? Why wouldn't he die trying to rescue her husband?

Charlie didn't speak of the accident and she couldn't bring herself to pry any further. She'd been told what happened. It was an accident, plain and simple. Miners accepted the risk to make the good money. Paul chose to put himself in danger to provide a good life for his family. Charlie accepted larger responsibilities, being the boss. He was responsible for the safety of his crew. There were but a handful of lives with him, and Charlie chose to save a damned birdcage. God gave her strength to forgive. That didn't stop her from wishing she could hate him.

But he was just too good. Caleman men were chiseled from the block that way, apparently. Charlie offered to take them all in the day of the funeral service for Paul, but Rebecca waited, searching for enough work to cover her bank note. She finally conceded, but at least she'd tried.

Resilient to the point they earned a healthy dose of jealousy from Rebecca, the children meshed well with their cousins on the ranch, splitting the morning milking, stall mucking, and hay stacking duties up nine ways between them. Rebecca was guilt-ridden at first, bringing on more mouths to feed, but seeing how her children rose to the responsibilities of ranch life made her proud, lessening her remorse.

"It's just another glass of milk and baked potato," Charlie said, patting her shoulder. "We're family." His thin, forced smile was lost behind his coffee cup. "And besides, now that all your young 'uns are here, I haven't touched a shovel in weeks."

Rebecca nodded and smiled as best she could.

She did what she could do, keeping house with her sister-in-law, mending and sewing, cooking, and sketching free hand pictures to sell in town, earning a little money to help the family.

Not only did her art keep her hands busy, it helped when her mind began to race and she thought about the horrid death her husband suffered, his big, strong body torn apart, and her heart threatened to break all over again. It was during those times when she was most productive, creating beauty on plain parched, lifeless paper. Adding color like splashes of vibrant life, again jealous even of her own work, because the thing she gave to her work was the very essence she felt she lacked. She was a shell. An empty vessel, cold and echoing. A plain, white canvas, lacking vibrancy and lust for life. Depth of soul.

At first, she sketched things that comforted her. Sunshine on her husband's face in the morning. One of his eyes with a pool of color so deep she saw herself looking back, and heard him telling her, "You've got my heart, girl," like he did countless times to make her smile. She sketched his hands, strong when he provided for his family, soft as the fur of a cottontail when he touched her.

Gradually, she moved on to the beauty provided by the vast, mountainous acreage at the ranch. A doe and a fawn in a glade. A family of skunks with lively kittens wrestling by a stump at twilight. She'd walk for hours, watching the sun to keep her bearings, thrilling in her ability to see God in the scenes she found. Each span of beauty was a gift from above. All color in a sunrise was painted by angels; the same ones that kept their brushes nimble and moist, awaiting a clean palate for sunset.

One bright morning the most beautiful, enormous cougar was laid out on a ledge across a crag. The mountain lion's gaze was locked on her, so it appeared to have been watching as she meandered the wilderness, one big paw bent at the wrist and dangling from the slab. From her vantage, she guessed it to be much larger than she, outweighing her by over fifty pounds. If the thing got a hair, it could likely clear the chasm separating them, but it reclined, instead watching her every step with tawny-gold eyes.

She'd never considered the color of a wild cat's eyes before. They stood out beautifully in the fawn-colored face, contrasting, soft white blending at the jaw and continuing along the cat's underneath. Its belly rose and fell, and she fancied she heard the deep rumbling purr as it blinked, basking, and watching. The massive tail twitched, the only agitated part of the animal, like a house cat cornered by an ornery toddler. It seemed caged then, perhaps stuck there on the ledge, trapped by its own cunning. She backed away with their eyes locked on each other, finally turning to run once the cat was out of sight.

The trip back to the ranch house was a quick one. Rebecca's heart pounded as she pulled a long canvas from behind the headboard in her bedroom and flattened in on the pad. She'd concentrated hard during the hike back, memorizing the subtleties along with the strengths of the picture in her mind's eye. When the canvas stared back at her, taunting with a question of blank lifelessness, she answered by laying out the sketch at a quick pace. It was her only large canvas, left over from months ago. The big ones were terribly expensive, but Rebecca knew it would soon be a painting, deeper and beautiful beyond anything she'd ever done. She created for hours, barely eating or sleeping between cycles of the sun.

Six days later Charlie hung the painting over the couch. The mountain lion gazed out from his perch above, swirling fog pooling deep in the crag below. Rebecca beamed with pride. The painting wouldn't be sold; it would hang for the family to enjoy. The children hugged her and told her it was brilliant. Charlie and his wife shook their heads, smiling at her talent. Soon, everyone went back to their preoccupations, leaving Rebecca standing in front of the painting, tears streaming her cheeks as she gazed into the feline eyes and saw herself looking back. Paul would have loved it.

* * *

Two days later Rebecca backed away from the door as her oldest niece sprinted through, sobbing, holding the hem of her skirts high as she ran. Charlie ducked through the door behind her, a switch poised in his huge right hand, but the girl continued through the room, quickly making herself lost in the sprawling house. He snapped the willow in half, bending it back once to sever the moist bark holding it together and flung it to the floor.

Not wanting to show the look of incrimination, one that she knew would reveal her shock, Rebecca dropped her gaze and said nothing, the only sound in the room the drawing of Charlie's ragged breath.

"Don't you say a bloody word," he growled.

"I wouldn't," she whispered, eyes still averted.

He stomped back outside, slamming the door.

Rebecca charged through the house, searching for the girl to see what could have prompted Charlie to act in such a manner. He was kind and patient as he was tall, and she'd never heard him raise his voice at one of his children, let alone whip one. Following the sound of the girl's sobs, she came to a closed door and pushed it open, intent on consoling the child. She stopped, hands falling limp to her sides.

Two of the girls had come to aid the child, having helped her out of her clothes. Tears streaked all the young women's faces. Their mother held an open tin of salve, eyes wide, surveying like she didn't know where to begin.

Welts rose on tender flesh at the backs of the girl's pale thighs, some to the point of tearing the skin. Bruising had begun in places, creating blotches of blackness scattered down a thin back, bottom and legs. The girl was in shock, hugging her frock against her chest, trembling as if she might freeze. She stared at Rebecca, teeth chattering.

"I left the gate open," she admitted.

"Has he ever—" Rebecca managed.

"No, he's never hit anyone," one of the distraught girls wailed, throwing her hands over her face.

Rebecca did the only thing she could think to do. She threw her arms around her bloodied niece and held her as she cried from the pain when her mother started slathering on the salve.

* * *

Charlie apologized. He wept. Promised he'd never lose his temper again. Days went by, and one night when Rebecca couldn't hold her bladder until morning, she passed Charlie as he slept on the couch, the mountain lion in the painting watching him breathe. She didn't want to think of the trouble that could be between Charlie and his wife, but after such an occurrence, it was likely. He'd probably been stuck out on the couch since that day. Carefully and quiet so she didn't wake him, she made her way out to relieve herself and back inside before he'd turned over.

Although apologies continued to flow, the mood around the ranch was somber. Children didn't chase. If conversation took place, it stopped when Charlie came around. Rebecca couldn't help but feel bad for him, and she ached for the family that had lost trust. She didn't get involved, but she offered smiles, continued to help manage her niece's wounds with her sister-in-law and sketched from the scenes she found outside.

She'd started a new drawing of a big,bull elk she seen and heard bugling just down the draw. The picture came along nicely, although she'd been working on it for hours and her drawing hand cramped painfully. Setting her supplies aside, she changed for bed, and climbed beneath a thick cover of quilts.

Floorboards creaked on the other side of the door. Rebecca couldn't remember anyone being up as late as she was, but discounted the footsteps, deciding someone must have needed to go to the outhouse. A wind kicked up, screaming through trees out back. She closed her eyes.

Moments later a shrill scream tore through the slumbering ranch house. Rebecca ran from her room, listening, trying to control her own panic as she attempted to discern which child the horrible noise came from. Others ran about in the house, and she ran toward the sounds they made. Two girls stood in their open doorway.

"Back to bed," Rebecca commanded. The girls ran inside and closed their door. The boys' room was lit by a hand lantern, one child standing upright on his bed, a finger held out toward the doorway Rebecca had just stepped through.

The moment she was inside the room, bile rose in her throat when she inhaled. The smell of death coated the air like tar over a hot fencepost. She placed a hand over her mouth and nose, trying not to gag.

Charlie stood next to his son, rubbing his back.

"It's okay, we're all here," he said, with a calming tone. "It was just a nightmare."

"There was a man," the child said, voice shaking.

"Who?" Rebecca asked.

He jabbed a small finger at the dark hall. "He was a cat-man," he said, breaking down. He hid his face, embarrassed at his show of emotion.

His mother picked him off the bed, cradling him against her chest and hip as if he was a toddler. The boy melted against her, crying like he'd been beaten.

"Charlie, please go look outside to see if the dogs drug something dead up by the house," she said.

He nodded and left the room.

"Is there anything I can do?" Rebecca asked.

Her sister-in-law just shook her head, rocking her son. "I'll get him settled in. Go on to sleep, Becca."

Rebecca nodded and went to the door, grateful to get into some fresh air. Taking a turn down the hall, she stepped into the girls' room. Moonlight shone through a window, showing the scared girls were all lumped into two beds together, bodies huddled under covers. They peeked out, wide-eyed and fearful, but tucked firmly in their bunks.

"All's well. Just a bad dream." She smiled and left.

* * *

Thankfully, October brought peace to the Caleman ranch. Normalcy claimed its place, and Rebecca tried to get back to healing from her loss. Her children continued to do well on the ranch, and chores had expanded to include stacking wood for the winter and counting cattle before snow began to fly. Preserves were stored in the pantry. Lard was hauled into the kitchen in buckets, and the household waited out winter at the ready.

Days shortened and nights chilled at sundown. Out of need for something to do when it was dark just past afternoon, the children at the ranch fashioned a wind chime from the old birdcage their father had brought from the mine the day of the fatality. The dehydrated corpse of the yellow mining bird was discarded into the trees in back of the hen house.

Charlie hung the gift from a hook on the porch the next morning. The bars hung askew, creating an imbalanced tone, although the love with which it was created melded the notes into beautiful harmonies that charmed the wind on the lawn and gardens.

Rebecca was comfortable with letting her mind wander to better days and times when her heart was whole. She imagined her husband's deep, soothing voice before bed, his words masking the way she was the only person in the house that slept in a room by herself. Charlie and his wife went back to sharing their marriage bed. All the boys slept in grand beds in a cozy room, as did the girls. Charlie had said she would need privacy. It was a nice gesture. She hated it.

Each night was long, and she would sketch and paint until her hand ached and back was stiff from standing or hunching, depending on the size of the canvas. Working deep into each night, she tried to exhaust herself, because that was the only way she could fall asleep. She'd get changed, climb into bed, and think good, warm thoughts about her husband. Her mind relaxed as she thought of him, her body slackened, and she entered the comfort of sleep.

The sound of her bedroom door should have fully awakened her, but instead of being awake and alarmed when Charlie stepped in, she was confused and half asleep. He closed the door behind him and knelt beside her bed, peering into her face with a tender gaze. The potent smell of decay followed on his heels. One hand moved to her cheek, tracing the line of her jaw with a gentle touch. He lowered his face to barely an inch above hers, and just when she was about to say something— she didn't know what, exactly— but certainly something in protest, he clamped a big hand tightly over her mouth.

A man could do a lot with one hand. He tugged his belt loose from his britches. Tears contorted her vision in the low light as she searched his face for reason. Just a year apart, Charlie shared many features with her husband, Paul. They were the same height, and just as strong as one another, as well. He bared her quickly, and she continued to watch him as he worked to free their bodies for access. She tore at his skin, determined to leave marks, attempting to hurt him if even a little. His muscular chest hovered, touching her nose, and since she was forced to breathe only through one nostril that wasn't crushed closed, her senses filled with the scent of death. Eyes, black as hell itself, neared her own as he entered her. She wept, thinking how she knew she'd weep silently, even if his hand wasn't over her mouth. He moved slowly, iris-less eyes on hers, one free hand caressing parts of her like they were lovers. He kissed tears from her cheeks, closing her eyes with his lips.

"You've got my heart, girl," he whispered.

"Why?" she cried out, the wail smothered against his palm.

He stilled. "Because I love you. You wouldn't accept me if I didn't come to you with this man." He let his gaze take in the curve of her jaw, the deep pools of tears in her eyes. "I regard you as you wander. You call me forth."

Rebecca searched Charlie's eyes but found only blackness, the likes of a deep, light-forbidding cave. Whatever crept above her then wasn't her brother-in-law, or her beloved Paul. Lord God, why? Heavenly Father… please help me….

But he touched her like her husband, felt just like him everywhere. He moved as her Paul did, touching the places she loved to be touched, relentlessly. Rebecca wondered if it was her mind doing it all, masking him, giving her a sickening parody of intimacy she knew she would never have again.

Exhaustion from straining and fighting won out and her grip relaxed on his forearm, fingernails sliding from the bloodied grooves in the flesh there. Charlie removed his hand and replaced it with his lips, her husband's lips, quickening his pace with frantic thrusts.

When Charlie left Rebecca, she pulled her quilts up to her chin, closed her eyes, and prayed to continue to dream.