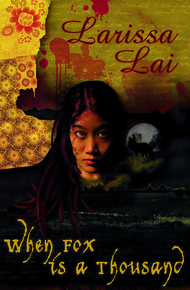

When Fox Is a Thousand is a lyrical, magical story, a spirited retelling of the old Chinese folktale of the Fox. In Larissa Lai's compelling first novel, a fox spirit comes to haunt the oddly named Artemis Wong, a young woman living in Vancouver. The fox brings with her the history of another haunting, that of the T'ang Dynasty poet Yu Hsuan-Chi, who was accused, perhaps wrongly, of having murdered the young maid servant who once worked for her.

One part history, one part fairytale, one part urban discontent, this delightful novel cracks open all preconceptions of Asian women, gender, sexuality, family, faith, and the flow of time. Smart, funny, and fully imagined, When Fox Is a Thousand is beautiful, enchanting, and composed with a sure narrative hand. Lai's potent imagination and considerable verbal skill result in a tale that continues to haunt long after the story is told.

When Fox Is a Thousand is a lyrical, magical story, a spirited retelling of the old Chinese folktale of the Fox. In Larissa Lai's compelling first novel, a fox spirit comes to haunt the oddly named Artemis Wong, a young woman living in Vancouver. The fox brings with her the history of another haunting, that of the T'ang Dynasty poet Yu Hsuan-Chi, who was accused, perhaps wrongly, of having murdered the young maid servant who once worked for her.

One part history, one part fairytale, one part urban discontent, this delightful novel cracks open all preconceptions of Asian women, gender, sexuality, family, faith, and the flow of time. Smart, funny, and fully imagined, When Fox Is a Thousand is beautiful, enchanting, and composed with a sure narrative hand. Lai's potent imagination and considerable verbal skill result in a tale that continues to haunt long after the story is told.

When Fox Is a Thousand's narrative strands and lyrical language mirror the magic of its tale. The fox spirit mythology and historical memoir alone are well worth a read, but the way Lai deftly handles the convergences and spaces between these narratives and that of Artemis, a young Chinese Canadian woman, is well worth a second, or third, read. – Tenea D. Johnson

"A particularly acute pleasure."

– The Advocate"Majestically written, with wild but contained imagery."

– Vancouver Sun"A magical book . . . Lai moves with a sure hand . . . her potent imagination and considerable verbal skill result in a tale that continues to haunt long after the book is closed."

– Books in CanadaI come from an honest family of foxes. They were none too pleased about my forays into acts of transformation. When they found out about the scholars I visited on dark nights, haunting them in the forms of various women, they were appalled. They love me too much to disown me for a trait that has run in the family for generations, although it is seldom openly discussed. They said, "Don't you know your actions reflect on us all? If you keep making these visitations, other fox families will talk about us. They will criticize us for not having raised you properly. It would be better if you chose a more respectable occupation, like fishing or stealing chickens."

They got even more upset when I started to counsel a housewife. She was lovely. Her flesh glowed like translucent jade. Her husband owned rice fields and horses. He owned vaults of silk and gold. His eyes were quick, his beard thick and warlike. He dressed in elegant blues and browns, aristocratic but not frivolous, and rode a muscular horse with a tendency to wildness. But he handled his wife the way he handled money – with cold, calculating fingers. She responded warmly to his looks. But to his cold hands, she responded the way one does to winter, drawing the blankets tighter and waiting for it to end. He decided there was something wrong with her. Hadn't he, after all, treated her as though she were the most precious thing on earth?

He asked her to buy him a concubine, as men often asked their wives in those days. She agreed readily, pleased with the possibility that, if she chose right, she could endear him further to her and at the same time escape that wifely duty that had become increasingly disagreeable. She chose a plump and giddy girl who did not mind the cold. He was delighted and forgot about his wife altogether. She did not realize until too late that without his affection, she would lose her authority over the servants. The house fell into disrepair. Only then did she discover that she needed him more than she thought. She could do nothing but put gold and jade in her hair and wait. She might as well have packed her bags and moved into the vaults.

I moved in next door and began to offer advice. So what if the body I occupied was not my own? One must take human form to engage in human affairs. It was difficult. I had not come fully into my powers, and could maintain the form for only a few hours at a time.

I instructed her not to bathe. I wrapped her perfect body in the flea-ridden hand-me-downs of a beggar. I set her to work on the soot-encrusted stove with a worn shoe brush. I smeared her face with fat and ashes, and taught her to sing a heart-rending tune. The concubine took pity and offered to help, but the housewife chased her away. She scoured the floors. She scrubbed the chamber pots until they shone like the sun. The concubine came again to offer assistance, which my charge would have accepted had I not hissed at her from my hiding place outside the kitchen window. She grew thin and even the husband began to worry. He came and implored her to leave the work to the sturdier women of the house, but she chased him away crossly.

At the end of a month, I took her to my own room and dressed her in emerald silk. Long sleeves cut in the latest fashion. On her dainty feet I slipped a pair of shoes I had embroidered with my own hands. In the morning when the roses smelled sweet, I sent her into her garden, where the husband and concubine leaned over a chessboard. The husband was enraptured. He asked her to join them, but she refused, saying she was tired, and hurried off to her room.

The following day, I invited her over again. I draped her in a robe the colour of moving water. I gave her shoes made by my elder sister, who had a finer hand than I. At nightfall, when the scent of jasmine permeated the air, I guided her into the garden, where the husband and concubine sat drinking tea and composing couplets under the full moon. Again he approached her. She led him and the concubine to her chambers. In the hallway the concubine turned to her and raised a curious eyebrow. The housewife pushed them both into her room and locked the door behind them, whispering as she turned the key that she was tired and wished to be left alone. Then she went off to sleep in the concubine's room.

On the third day, she came to see me on her own. I wrapped her in a gown the colour of the sky before a storm. On her feet I placed shoes made by my younger sister, whose hand was so fine you could not discern the individual threads of her embroidery. I pushed her into the garden at midnight, when the scent of every jasmine flower and every sandalwood tree infused the senses, so that those who lingered there were made blind and deaf by the aroma. As a farewell gift, I taught her how kisses come not from the mouth, but from a well deep below the earth. The husband was smitten.

Is it my fault she ran off with the concubine?

Other foxes thought so, and chalked it up to the evil influence of the West, where personal whim comes before family pride and reputation. Westerners had been coming and going from the capital for hundreds of years. Their manner of dress had become fashionable among the students and courtesans. Their strange religions less so. Their horses – everyone wanted their horses, except, perhaps, us foxes.

Other foxes chastise me for my unorthodox methods. But I don't know why they should pretend to know so much about human affairs, since they don't engage in them. Their scorn, on the other hand, I understand well enough.

Human history books make no room for foxes. But talk to any gossip on the streets or any popcorn-munching movie-goer, and they will tell you that foxes of my disposition have been around since before the first dynasty.

I got worse when we emigrated to the west coast of Canada. The whole extended family came for the opportunities, not knowing that migration fundamentally and permanently changes value systems. My penchant for nightly roamings ceased to be a mere quirk of character, but rather became an entire way of life. I like to fish, and I like to steal chickens. But I don't do either anymore, except on those rare occasions when courtesy demands it.

In due time, the foxes of my fox hole got used to what they called my unnatural behaviour. They did not mind what I did or where I went, although they would never do such things themselves. "But," they said, "do you have to write about it?"

When I wrote about the thrill that comes from animating the bodies of the dead, they swept their bushy tails in the dirt in disgust and said they didn't want anything more to do with me.

And that is how it happens that I live alone.