Andy Duncan's short fiction has been honored with the Nebula, Sturgeon, and multiple World Fantasy awards. A native of Batesburg, SC, Duncan has been a newspaper reporter, a trucking-magazine editor, a bookseller, a student-media adviser, and, since 2008, a member of the writing faculty at Frostburg State University in the mountains of western Maryland, where he lives with his wife, Sydney.

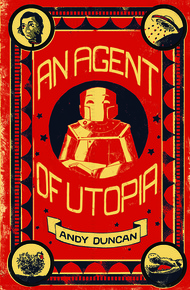

In the tales gathered in Locus and World Finalist Award finalist An Agent of Utopia: New and Selected Stories you will meet a Utopian assassin, an aging UFO contactee, a haunted Mohawk steelworker, a time-traveling prizefighter, a yam-eating Zombie, and a child who loves a frizzled chicken—not to mention Harry Houdini, Zora Neale Hurston, Sir Thomas More, and all their fellow travelers riding the steamer-trunk imagination of a unique twenty-first-century fabulist.

From the Florida folktales of the perennial prison escapee Daddy Mention and the dangerous gator-man Uncle Monday that inspired "Daddy Mention and the Monday Skull" (first published in Mojo: Conjure Stories, edited by Nalo Hopkinson) to the imagined story of boxer and historical bit player Jess Willard in World Fantasy Award winner "The Pottawatomie Giant" (first published on SciFiction), or the Ozark UFO contactees in Nebula Award winner "Close Encounters" to Flannery O'Connor's childhood celebrity in Shirley Jackson Award finalist "Unique Chicken Goes in Reverse" (first published in Eclipse) Duncan's historical juxtapositions come alive on the page as if this Southern storyteller was sitting on a rocking chair stretching the truth out beside you.

Duncan rounds out his explorations of the nooks and crannies of history in two irresistible new stories, "Joe Diabo's Farewell" — in which a gang of Native American ironworkers in 1920s New York City go to a show — and the title story, "An Agent of Utopia" — where he reveals what really (might have) happened to Thomas More's head.

Andy Duncan is one of my favorite readers, and in An Agent of Utopia he's amassed a collection of memorable tales rich in language, imagery, and characterization. If you're lucky and listen closely you just might hear his soft, compelling drawl spinning these tales and drawing you in. – Tenea D. Johnson

"Reading Duncan can feel like being taken on a tour of your own dusty attic and being shown treasures you didn't know you had."

– Chicago Tribune"Whatever the topic, all of Duncan's fictions are united by an evocative, playful, and deeply accomplished storytelling style. Highly recommended for fans of Kelly Link or other slipstream writers, and for any reader looking to lose themselves in an engaging and fun reading experience."

– Booklist (starred review)"Zany and kaleidoscopic, the 12 stories in Duncan's third collection draw on Southern traditions of tall tales and span time periods, continents, and the realm of human imagination to create an intricate new mythology of figures from history, literature, and American folklore. . . .This is a raucous, fantastical treat."

– Publishers Weekly (starred review)I ever tell you about the time Cliffert Corbett settled a bet by outrunning a bullet? Oh. Well, all right, Little Miss Smarty Ass, here it is again, but this time I'll stick to the truth, because I got enough sins to write out on St. Peter's blackboard as it is, thank you, and on the third go-round the truth is easiest to remember. So you just write down what I tell you, just as I tell you, and don't put in none of your women's embroidery this time.

You're too young to remember Cliffert Corbett, I reckon, but he was the kind that even if you did remember him, you wouldn't remember him, except for this one thing that I am going to tell you, the one remarkable thing he ever did in his life. It started one lazed-out, dragged-in Florida afternoon outside the gas station, when we were all passing around a sack of boiled peanuts and woofing about who was the fastest.

During all this, Cliffert hadn't said nothing, and he hadn't intended to say nothing, but Cliffert's mouth was just like your mouth and mine. Whenever it was shut it was only biding its time, just waiting for the mind to fall down on the job long enough for the mouth to jump into the gap and raise some hell. So when Cliffert squeezed one boiled peanut right into his eye and blinded himself, his mouth was ready. As he blinked away the juice, his mouth up and blabbed: "Any of you fast enough to outrun a bullet?"

They all turned and looked at him, and friend, he wasn't much to look at. Cliffert was built like a fence post, and a rickety post, too, maybe that last post standing of the old fence in back of the gas station, the one with the lone snipped rusty barbed-wire curl, the one the bobwhites wouldn't nest in, because the men liked to shoot at it for target practice. And everyone knew that if Cliffert, with his gimpy leg, was to race that fence post, their money would be elsewhere than on Cliffert.

And because what Cliffert had said wasn't joking like, but more angry, sort of a challenge, Isiah Bird asked, "You saying you can do that?"

And just before Cliffert got the last bit of salt out of his eyes, his mouth told Isiah, "I got five dollars says I can, Isiah Bird."

From there it didn't matter how shut Cliffert's mouth was, because before he knew what hit him Isiah had taken that bet, and the others had jumped in and put down money of their own, and they were hollering for other folks on the street to come get in on the action, and Dad Boykin made up a little register that showed enough money was riding on this to have Cliffert set for life if he just could outrun a bullet, which everyone in town knew he couldn't do, including Cliffert, plus he didn't have no five dollars to lose.

"We'll settle this right now," said Pump Jeffries, who ran the gas station. "I got my service pistol locked up in the office there, but it's well greased and ready to go."

"Hold on!" cried Cliffert, and they all studied him unfriendly like, knowing he was about to back out on the deal his mouth had made.

"I got to use my own gun," Cliffert said, "and my own bullets."

They all looked at each other, but when Isiah Bird nodded his head, the others nodded, too. "Fetch 'em, then," Dad Boykin said. "We'll wait right here."

"Now, boys," said Cliffert, thinking faster than he could run, "you got to give me some time to get ready. Because this ain't something you can just up and do, no matter how fast you are. You got to practice at it, work up to it. I need to get in shape."

"Listen at him now. He wants to go into training!"

"How long you need, then?"

"A year," Clifford said. "I'll outrun a bullet one year from this very day, the next twenty-first of July, right here in front of the gas station, at noon."

No one liked this very much, because they were all raring to go right then. But they talked it over and decided that Cliffert wasn't going to be any more able to outrun a bullet in a year than he was now.

"All right, Cliffert," they told him. "One year from today."

So then Cliffert limped on home, tearing his hair and moaning, cursing his fool mouth for getting him into this fix.

He was still moaning when he passed the hoodoo woman's house. You could tell it was the hoodoo woman's house because the holes in the cement blocks that held it up were full of charms, and the raked patterns in the dirt yard would move if you looked at them too hard, and the persimmon trees were heavy with blue bottles to catch spirits, and mainly because the hoodoo woman herself was always sitting on the porch, smoking a corncob pipe, at all hours and in all weathers, because her house was ideally situated to watch all the townsfolk going and coming, and she was afraid if she ever went inside she might miss something.

"What ails you, Cliffert Corbett, that you're carrying on such a way?"

So Cliffert limped into her yard, taking care not to step on any of the wiggly lines, and told her the whole thing.

"So you see, Miz Armetta, I won't be able to hold my head up in this town no more. I'll have to go live in Tallahassee with the rest of the liars."

The hoodoo woman snorted. "Just tell 'em you can't outrun a bullet, that you're sorry you stretched it any such a way. Isiah Bird keeps cattle and hogs both, and he'll let you work off that five dollars you owe him."

When he heard the word 'work,' Cliffert felt faint, and the sun went behind a cloud, and the dirt pattern in the yard looked like a big spider that crouched and waited.

"Oh, Miz Armetta, work is a harsh thing to say to a man! Ain't you got any other ideas for me than that?"

"Mmmph," she said, drawing on her pipe. "The holes men dig just to have a place to sit." She closed her eyes and rocked in her shuck chair and drummed her fingertips on her wrinkled forehead and asked, "They expecting you to use your own bullet?"

"Yes, and my own gun."

"Well, it's simple then," she said. "You need you some slow bullets."

"What you mean, slow bullets? I never heard tell of such a thing."

"I ain't, either," said the hoodoo woman, "but you got a year to find you some, or make you some."

Cliffert studied on this all the way home. There he lifted his daddy's old service pistol and gun belt out of the cedar chest and rummaged an old box of bullets out of the back corner of the Hoosier cabinet and set them both on the kitchen table and sat down before them. He rested his elbows on the oilcloth and rested his chin on his hands. He wasn't used to thinking, but now that first Isiah Bird and now the hoodoo woman had got him started in that direction, he was sort of beginning to enjoy it. He studied and studied, and by sunset he had his breakthrough.

"The bullet is just a lump of metal," he told the three-year-and-two-month-old Martha White calendar that twitched and tapped the wall in the evening breeze. "It's the powder in the cartridge that moves it along. So what I need is slow powder. But what would go into slow powder?"

He grabbed a stubby pencil, and on the topmost Tallahassee Democrat on a stack bound for the outhouse, he began to make a list of slow things.

For week after week, month after month, Cliffert messed at his kitchen table, and then in his back yard, with his gunpowder recipe, looking for the mix that gave a bullet the slowest start possible while still firing. First he ground up some snail shells and turtle shells and mixed that in. He drizzled a spoonful of molasses over it and made such a jommock that he had to start over, so from then on, he used only a dot of molasses in each batch, like the single roly-poly blob Aunt Berth put in the middle of her biscuit after the doctor told her to mind her sugar. For growing grass he had to visit a neighbor's yard, since his own yard was dirt and unraked dirt at that, but the flecks of dry paint were scraped from his own side porch and in the sun, too, which was one job of work. He tried recipe after recipe, a tad more of this and a teenchy bit less of that, and went through three boxes of bullets test-firing into a propped-up Sears, Roebuck catalog in the back yard, and even though the boxes emptied ever more slowly, he still was dissatisfied. Then one day he went to Fulmer's Hardware and told his problems to the man himself.

"You try any wet paint?" Mr. Fulmer asked.

"No," Cliffert said. "Just the flakings. How come you ask me that?"

"Well, I was just thinking," Mr. Fulmer said. He laid the edge of his left hand down on the counter, like it was slicing bread. "If wet paint is over here." He held his left hand still and laid down the edge of his right hand about ten inches away. "And dry paint is over here, and it goes from the one to the other, it stands to reason that the wet paint is slower than the dry, since it ain't caught up yet."

Cliffert studied Mr. Fulmer's hands for a spell. The store was silent, except for the plip plip plip from the next aisle. They couldn't see over the shelf but knew it was six-year-old Louvenia Parler, who liked to wait for her mama in the hardware store so she could play with the nails.

"That stands to reason," Cliffert finally said, "only if the wet paint is as old as the dry paint, so we know they started at the same time."

Mr. Fulmer folded his arms. "Now you talking sense. When you last paint your side porch?"

"I myself ain't never painted it, nor the front porch nor no other part of the house. It don't look like it's been painted since God laid down the dirt to make the mountains."

"That might be the original paint, sure enough, so you're out of luck. I don't stock no seventy-five-year-old paint."

"How old you got?"

Mr. Fulmer blew air between his lips like a noisemaker. "Ohh, let's see. I probably got paint about as old as Louvenia."

"Well, even Mr. Ford started somewhere. Let me have a gallon of the oldest you got."

Mr. Fulmer asked, "What color?" And before he even could regret asking, Cliffert said:

"Whatever color's the slowest, that's the one I want." I ever tell you about the time Cliffert Corbett settled a bet by outrunning a bullet? Oh. Well, all right, Little Miss Smarty Ass, here it is again, but this time I'll stick to the truth, because I got enough sins to write out on St. Peter's blackboard as it is, thank you, and on the third go-round the truth is easiest to remember. So you just write down what I tell you, just as I tell you, and don't put in none of your women's embroidery this time.

You're too young to remember Cliffert Corbett, I reckon, but he was the kind that even if you did remember him, you wouldn't remember him, except for this one thing that I am going to tell you, the one remarkable thing he ever did in his life. It started one lazed-out, dragged-in Florida afternoon outside the gas station, when we were all passing around a sack of boiled peanuts and woofing about who was the fastest.

During all this, Cliffert hadn't said nothing, and he hadn't intended to say nothing, but Cliffert's mouth was just like your mouth and mine. Whenever it was shut it was only biding its time, just waiting for the mind to fall down on the job long enough for the mouth to jump into the gap and raise some hell. So when Cliffert squeezed one boiled peanut right into his eye and blinded himself, his mouth was ready. As he blinked away the juice, his mouth up and blabbed: "Any of you fast enough to outrun a bullet?"

They all turned and looked at him, and friend, he wasn't much to look at. Cliffert was built like a fence post, and a rickety post, too, maybe that last post standing of the old fence in back of the gas station, the one with the lone snipped rusty barbed-wire curl, the one the bobwhites wouldn't nest in, because the men liked to shoot at it for target practice. And everyone knew that if Cliffert, with his gimpy leg, was to race that fence post, their money would be elsewhere than on Cliffert.

And because what Cliffert had said wasn't joking like, but more angry, sort of a challenge, Isiah Bird asked, "You saying you can do that?"

And just before Cliffert got the last bit of salt out of his eyes, his mouth told Isiah, "I got five dollars says I can, Isiah Bird."

From there it didn't matter how shut Cliffert's mouth was, because before he knew what hit him Isiah had taken that bet, and the others had jumped in and put down money of their own, and they were hollering for other folks on the street to come get in on the action, and Dad Boykin made up a little register that showed enough money was riding on this to have Cliffert set for life if he just could outrun a bullet, which everyone in town knew he couldn't do, including Cliffert, plus he didn't have no five dollars to lose.

"We'll settle this right now," said Pump Jeffries, who ran the gas station. "I got my service pistol locked up in the office there, but it's well greased and ready to go."

"Hold on!" cried Cliffert, and they all studied him unfriendly like, knowing he was about to back out on the deal his mouth had made.

"I got to use my own gun," Cliffert said, "and my own bullets."

They all looked at each other, but when Isiah Bird nodded his head, the others nodded, too. "Fetch 'em, then," Dad Boykin said. "We'll wait right here."

"Now, boys," said Cliffert, thinking faster than he could run, "you got to give me some time to get ready. Because this ain't something you can just up and do, no matter how fast you are. You got to practice at it, work up to it. I need to get in shape."

"Listen at him now. He wants to go into training!"

"How long you need, then?"

"A year," Clifford said. "I'll outrun a bullet one year from this very day, the next twenty-first of July, right here in front of the gas station, at noon."

No one liked this very much, because they were all raring to go right then. But they talked it over and decided that Cliffert wasn't going to be any more able to outrun a bullet in a year than he was now.

"All right, Cliffert," they told him. "One year from today."

So then Cliffert limped on home, tearing his hair and moaning, cursing his fool mouth for getting him into this fix.

He was still moaning when he passed the hoodoo woman's house. You could tell it was the hoodoo woman's house because the holes in the cement blocks that held it up were full of charms, and the raked patterns in the dirt yard would move if you looked at them too hard, and the persimmon trees were heavy with blue bottles to catch spirits, and mainly because the hoodoo woman herself was always sitting on the porch, smoking a corncob pipe, at all hours and in all weathers, because her house was ideally situated to watch all the townsfolk going and coming, and she was afraid if she ever went inside she might miss something.

"What ails you, Cliffert Corbett, that you're carrying on such a way?"

So Cliffert limped into her yard, taking care not to step on any of the wiggly lines, and told her the whole thing.

"So you see, Miz Armetta, I won't be able to hold my head up in this town no more. I'll have to go live in Tallahassee with the rest of the liars."

The hoodoo woman snorted. "Just tell 'em you can't outrun a bullet, that you're sorry you stretched it any such a way. Isiah Bird keeps cattle and hogs both, and he'll let you work off that five dollars you owe him."

When he heard the word 'work,' Cliffert felt faint, and the sun went behind a cloud, and the dirt pattern in the yard looked like a big spider that crouched and waited.

"Oh, Miz Armetta, work is a harsh thing to say to a man! Ain't you got any other ideas for me than that?"

"Mmmph," she said, drawing on her pipe. "The holes men dig just to have a place to sit." She closed her eyes and rocked in her shuck chair and drummed her fingertips on her wrinkled forehead and asked, "They expecting you to use your own bullet?"

"Yes, and my own gun."

"Well, it's simple then," she said. "You need you some slow bullets."

"What you mean, slow bullets? I never heard tell of such a thing."

"I ain't, either," said the hoodoo woman, "but you got a year to find you some, or make you some."

Cliffert studied on this all the way home. There he lifted his daddy's old service pistol and gun belt out of the cedar chest and rummaged an old box of bullets out of the back corner of the Hoosier cabinet and set them both on the kitchen table and sat down before them. He rested his elbows on the oilcloth and rested his chin on his hands. He wasn't used to thinking, but now that first Isiah Bird and now the hoodoo woman had got him started in that direction, he was sort of beginning to enjoy it. He studied and studied, and by sunset he had his breakthrough.

"The bullet is just a lump of metal," he told the three-year-and-two-month-old Martha White calendar that twitched and tapped the wall in the evening breeze. "It's the powder in the cartridge that moves it along. So what I need is slow powder. But what would go into slow powder?"

He grabbed a stubby pencil, and on the topmost Tallahassee Democrat on a stack bound for the outhouse, he began to make a list of slow things.

For week after week, month after month, Cliffert messed at his kitchen table, and then in his back yard, with his gunpowder recipe, looking for the mix that gave a bullet the slowest start possible while still firing. First he ground up some snail shells and turtle shells and mixed that in. He drizzled a spoonful of molasses over it and made such a jommock that he had to start over, so from then on, he used only a dot of molasses in each batch, like the single roly-poly blob Aunt Berth put in the middle of her biscuit after the doctor told her to mind her sugar. For growing grass he had to visit a neighbor's yard, since his own yard was dirt and unraked dirt at that, but the flecks of dry paint were scraped from his own side porch and in the sun, too, which was one job of work. He tried recipe after recipe, a tad more of this and a teenchy bit less of that, and went through three boxes of bullets test-firing into a propped-up Sears, Roebuck catalog in the back yard, and even though the boxes emptied ever more slowly, he still was dissatisfied. Then one day he went to Fulmer's Hardware and told his problems to the man himself.

"You try any wet paint?" Mr. Fulmer asked.

"No," Cliffert said. "Just the flakings. How come you ask me that?"

"Well, I was just thinking," Mr. Fulmer said. He laid the edge of his left hand down on the counter, like it was slicing bread. "If wet paint is over here." He held his left hand still and laid down the edge of his right hand about ten inches away. "And dry paint is over here, and it goes from the one to the other, it stands to reason that the wet paint is slower than the dry, since it ain't caught up yet."

Cliffert studied Mr. Fulmer's hands for a spell. The store was silent, except for the plip plip plip from the next aisle. They couldn't see over the shelf but knew it was six-year-old Louvenia Parler, who liked to wait for her mama in the hardware store so she could play with the nails.

"That stands to reason," Cliffert finally said, "only if the wet paint is as old as the dry paint, so we know they started at the same time."

Mr. Fulmer folded his arms. "Now you talking sense. When you last paint your side porch?"

"I myself ain't never painted it, nor the front porch nor no other part of the house. It don't look like it's been painted since God laid down the dirt to make the mountains."

"That might be the original paint, sure enough, so you're out of luck. I don't stock no seventy-five-year-old paint."

"How old you got?"

Mr. Fulmer blew air between his lips like a noisemaker. "Ohh, let's see. I probably got paint about as old as Louvenia."

"Well, even Mr. Ford started somewhere. Let me have a gallon of the oldest you got."

Mr. Fulmer asked, "What color?" And before he even could regret asking, Cliffert said:

"Whatever color's the slowest, that's the one I want."